Composer and Musician Michael Brook on “Heat,” U2 and Hans Zimmer

Dec 13, 2025

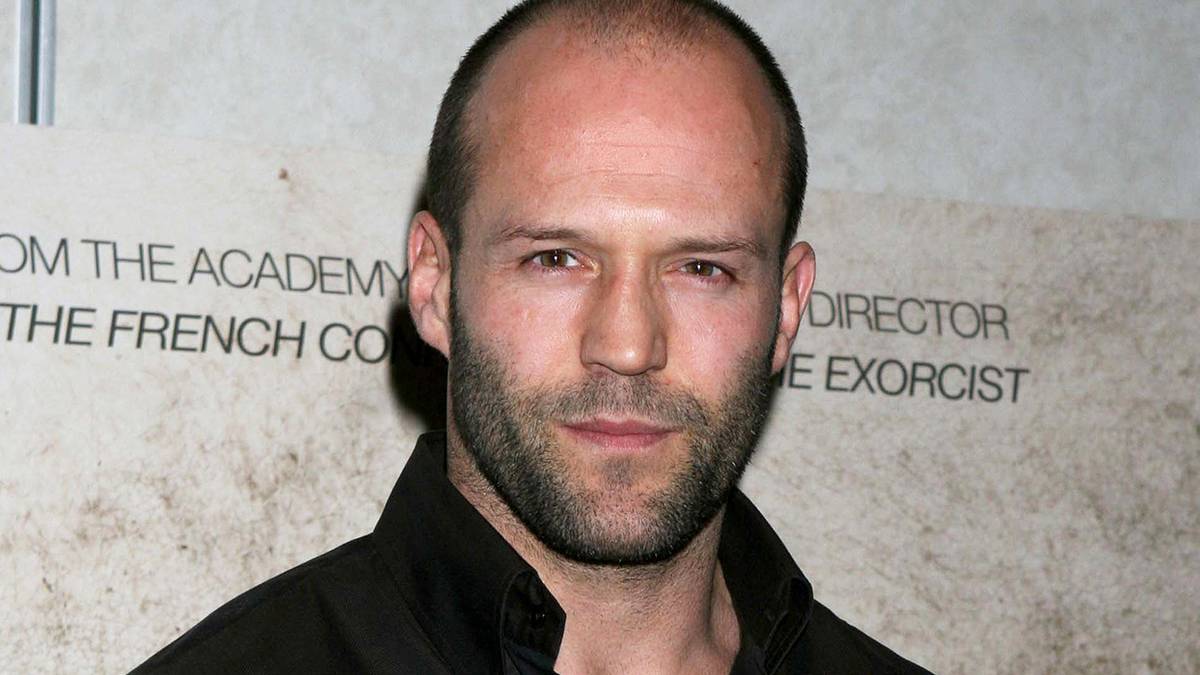

MIchael Brook

Michael Brook has collaborated with some of the most influential filmmakers and musicians of the last 40 years without ever threatening to become a household name. When I spoke to the inventor and composer last month at the Warsaw Film Festival, I asked if he valued the recognition of awards bodies, to which he explained with typical candor that “almost everything I do is not the kind of thing that the Academy is interested in, and that’s fine.” Brook got his first break in 1984 when he convinced Brian Eno, then a customer in the Toronto video lab where he worked, to collaborate with him on his debut album, Hybrid. From that meeting came another with U2’s The Edge, who would eventually use one of Brook’s inventions, the Infinite Guitar, on With or Without You.

When it comes to the world of cinema, Brook’s early rise was similarly unconventional. He got another break when Michael Mann heard a piece of his music on KCRW and asked him to contribute to the score for Heat (you can hear one of his tracks, a jangly guitar number called “Ultramarine,” during the Chinese restaurant surveillance scene). From there, Brook went on to work with Hans Zimmer on Black Hawk Down and Sean Penn on Into the Wild—the latter of which earned him a nomination at the Golden Globes but, much to Penn’s chagrin, was deemed ineligible by the Academy for having, as Brook puts it, “too many songs.” The closest he’s come to winning one of the industry’s main prizes was for Night Song, a collaboration with the traditional qawwali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, released on Peter Gabriel’s Real World records, which lost the 1997 Grammy for World Music to The Chieftains but made him a superstar (his word) in Pakistan.

We met almost by chance in the Polish capitol, where Brook had made the unusual decision to attend with the team of Anorgasmia, an Icelandic film from Jon Gustafsson, and Beautiful Evening, Beautiful Day, from the Croatian filmmaker Ivona Juka. For 90 minutes, over Caesar salad and coffees, in a cafe somewhere in the Palace of Science and Culture (a Stalinist behemoth that still dominates the city’s otherwise glassy skyline), Brook took the time to talk a bit about Mann, Penn and Eno and some of the projects and encounters that brought him to where he is today. The following conversation was edited and condensed for clarity.

Filmmaker: When I heard that you were attending, it made me wonder if you’d ever performed at a film festival before?

Brook: Yes, at Sundance actually. I can’t even remember which film. ASCAP does a thing to promote composers there, so I might not have had a film that year. But I’ve been to Sundance two or three other times. It’s nice to go there for the film and all, but I don’t really go to festivals much. As a composer, it’s like you’re up against the window of a candy store, looking in. There’s no business reason to be there.

Filmmaker: I was talking to Jon Gustafsson, your director on Anorgasmia, at the party on Friday. He was telling me about how you came to him with this idea of having two notes just slightly out of tune, to kind of represent the characters being on slightly different wavelengths. Do you usually think about your work in this conceptual way?

Brook: No [laughs]. For me, that’s part of the discovery process. I really don’t preconceive music. When we’re first talking about the film or spotting, there’s always talk of themes and all that—“Is this her theme or his theme?”—and it just never works out., so I don’t even bother thinking about that. Maybe it works for some composers, but not me,

Filmmaker: In your experience, have directors mostly left you to your own devices?

Brook: It varies a lot. Brooklynwas a very difficult but rewarding project. Nobody was being difficult, it just was a challenge. John [Crowley], the director, had a sort of mental, emotional map of each shot, and I had never worked at that level of detail. So, I was a bit out of my comfort zone, which is ultimately always a good thing. But at the time, it’s not comfortable.

Filmmaker: When you started working in cinema, was that connection somehow a result of your early collaborations with Brian Eno?

Brook: The first film thing I did was a project called Captive, with The Edge. He hadn’t done a score before, but we had met, and he said, “You want to help me with it?” After that, I didn’t do anything for quite a while. Then I did an IMAX film about putting out oil fires in Kuwait; that was through Peter Gabriel, who they’d asked to do it and he suggested they talk to me. Then I got a couple of features, but I still didn’t know how to do it.

Filmmaker: You worked with Paul Schrader pretty early on, right? I feel like he’s always been quite particular about music in his films. How did it come about that you ended up doing the score for Affliction? That film was also a change of pace for him, this more Northern, woodland area.

Brook: Yeah, he doesn’t usually do small towns [laughs]. I can’t remember. Around the same time I did a film Kevin Spacey directed, which is the first feature I worked on as a composer by myself. I think what gave me a little bit of momentum was a piece of music I made, where I’m playing guitar sort of percussively and thumping it, which was on a solo album I did. Michael Mann heard it on the radio and asked me to get involved in Heat. Even though I didn’t do a lot on that movie, there’s a couple of good places where he used my music and I think that caused people in the industry to check me out.

Filmmaker: That came from Mann just hearing you on the radio?

Brook: Yeah, on KCRW. It was at a time when the music industry was a more meaningful thing, culturally. There was a DJ who did this show, Chris Douridas, who just had the best taste in music, and it was a time when a DJ’s choices could make a huge difference. I was living in Palo Alto then, so I came down to LA. They’d rented a studio. Some of the music ended up in the film, but not very much. He had six composers going at the same time, and he didn’t tell the composers that there were other people working on it [laughs].

Filmmaker: What catches your attention these days when people send you projects? How do you end up working on something like Anorgasmia?

Brook: It varies quite a lot. With this one, Jon calls it slow cinema,because one could argue not much happens in the film. There’s not a big plot, but it’s so powerful because of those static moments and amazing performances. So, I just connected with it emotionally and that’s the best way to decide.

Filmmaker: You also worked with Sean Penn on Into the Wild. Would you say you were collaborating more with Penn on that project or Eddie Vedder?

Brook: [With Vedder] it ended up not being so much of [a collaboration], although we sort of talked about trying to do that. Initially Sean wanted Eddie to do the songs and Gustavo Santaolalla to do some of the score, me to do some of it, and Kaki King, a really amazing guitar player. I think Gustavo just wasn’t into it: he sent some music in, Sean had some notes and Gustavo never seemed to change much [laughs]. So I ended up doing more of it.

FM: You went to the Golden Globes with that one.

Brook: Yeah, and my wife was so pissed. Because I think there was a strike or something, so they didn’t have the ceremony and she wanted to go to one of those events and it didn’t happen. And then there was this thing where Sean had a big fight with the Academy because they disallowed the score for having too many songs. And Sean was like, Yeah, but the songs are kind of inspired by a lot of the score, and they’re sort of part of the score, which I thought was an interesting approach. I get the rule is there because people would just pepper a movie with a bunch of hit songs or something like that. I get the need to somehow draw the line. But Sean thought, and I did too, that this was a different case.

Filmmaker: You live in Los Angeles?

Brook: Yeah, in the Hollywood Hills. I moved there in ‘99.

Filmmaker: What was the scene like when you got there? Pretty buzzing. I’d say.

Brook: I guess it was. I’ve never sort of connected with scenes. I’m not against it, it’s just nobody’s ever invited me [laughs]. I lived in London for about nine years, and there was a nice music community that I connected with.

Filmmaker: Is that how the U2 collaboration came about?

Brook: That happened through Brian Eno; he was producing them at the time. My day job in Toronto used to be running a video editing facility for artists. Brian lived in New York, but it was cheaper for him to fly up to Toronto to edit video at the place I worked at, so I was helping him for his video installations and things like that. Then he offered to pay me and I said, “Well, what about if we trade services and you help me make my first album?”Then he moved to London and was setting up a management company to deal with his own business needs, and he said that if I wanted, they would manage me as well. That’s when I decided to move to London and try to become a full time musician. Brian knew about the Infinite Guitar and thought The Edge might be interested, so he introduced us.

Filmmaker: Was that invention a lightbulb kind of moment?

Brook: It was more like building a campfire than a lightbulb. So, I saw a guitar player, Bill Nelson, play in Toronto. At the time I was just starting my first solo record and was interested in Indian music‚—ornamentation, gliding through or bending notes. So, Bill comes out and he’s playing with an EBow, this thing that vibrates the strings of the guitar, which is like the Infinite Guitar, but you had to hold it. I ordered one, but you know, no internet in those days, so I mailed the guy a check, but the guy was in California and he never received it. I’d booked studio time to start recording this album, so I thought, “Maybe I can make something,” so then I just started messing around with pickups and scotch tape. It was quite a Frankenstein thing, but it worked.

Filmmaker: Did you have a background in electronics or just played around with stuff?

Brook: I did consider it as a profession, but I just liked messing around. It was the same with music, actually. I would do experiments. I had a feel for it, but not much knowledge.

Filmmaker: I was listening to “With or Without You” on the walk here. I mean, if you asked someone to think of a U2 sound, nine out of 10 people would probably think of that sound. It’s iconic.

Brook: It is! And it’s interesting—and this is something I didn’t learn till recently—that recording, that tape, is the first time The Edge played it. They just got it out of the case, plugged it in and said, “Let’s try this.”

Filmmaker: I presume you don’t come from a classically trained music background. How did you start out with that?

Brook: No, I just played in bar bands in Toronto. Playing in bars is great. I think some of my favorite music experiences were in high school. We would play Thursday, Friday, Saturday night, and you get good at it. You’re playing from eight to one, three nights a week. It’s nice to get into that groove of playing live, almost like an athletic thing. I was considering a residency at Largo in LA. The problem was that a film would always come up and that’d be half my income for the year and tie me up for four months. That’s why I’m taking a break.

Filmmaker: Was making the transition to more ambient work a gradual process?

Brook: Sort of. There was a local art and music gallery in Toronto that had a studio you could rent for not much money, so I started working there. Then I got a little bit of my own recording equipment at home and started working on what became my first album. Then in London, there was a sort of loose community. You know the artist Russell Mills? He did a lot of album cover work for Brian Eno’s label, for John Foxx, David Sylvian. He really helped me a lot and was very supportive; he’d organize these concerts at the local church in Vauxhall, where he lived, and they were great. The Cocteau Twins would play with John Foxx and Dead Can Dance. People would go to his local pub every single night. Eventually people started calling it the Ambient Arms.

Filmmaker: Do you still mess around with instruments and hardware like you used to?

Brook: I messed around with electronics mostly. About a year ago, I thought I really wanted to take a break [from film] so I set up a nice workbench. I had never had the money before to do it properly, so I set it all up, because I had some ideas I wanted to work on. Then this film, Anorgasmia, came up, and I didn’t want to say no because it’s such a good filmSo, my workbench is just sitting there waiting [laughs].

Filmmaker: During this sabbatical, are you planning to work on a new album?

Brook: I actually just released an album with Nusrat [Fateh Ali Khan]. It was traditional music that we recorded at Real World Records 30 years ago and forgot about [laughs]. Somebody at Real World was doing inventory because they had to move their tape archive and came across these old tapes. They sent them to me and I said, “This is way better than what we put out.” I think it’s maybe his best work.

During the release, I was doing press and one of the people was an English Pakistani journalist and he said, “Why don’t you come to my wedding?” So, I arranged to go over and ended up giving a talk at the British Council in Islamabad and a performance. The big shock to me was that the album, Night Song, had changed Pakistani culture. People said, “Oh, I started working in music because of that.” Or they’ll talk about it like there was music “before Night Song“ and “after”. So, it had this huge influence there and apparently I’m a superstar there. They said, “Oh, we’re gonna have a party at this posh hotel.” And I said, “What’s it for?” “For you!”

Filmmaker: What was the connection with Nusrat originally?

Brook: I was a fan. When I went there first, whatever, 30 years ago, if you went into a music shop, there was all kinds of different music, but half the store was always Nusrat—he was sort of Elvis, The Beatles and Frank Sinatra rolled into one. So, Real World had licensed one of his existing recordings and wanted to do a collaboration, and Peter Gabriel asked me if I would do it because he’d heard a little bit of the Asian influence in my solo records.

Filmmaker: And Gabriel would have been heavily involved in that world music scene?

Brook: Very much so. He didn’t start it, but he was the driving force behind WOMAD, the World of Music and Dance concerts, then he started Real World Records, which is 99% what was called “world music” at that time.

Filmmaker: That genre had a bad reputation for a while but I feel like it’s kind of back. It’s like Enya in Ireland. She was very uncool for a while but now she’s massive again.

Brook: The music world itself has changed a lot. Things that were once considered too out there or too abstract, or whatever, are quite popular, which was another reason I thought It’s not a bad time to try and do something new.

Filmmaker: There are a few other titles from your career that I’m curious about. You’re credited as “guitar soloist” on the movie Transformers. Did that involve a lot of shredding?

Brook: I don’t remember what I did, but I can’t shred, so I know it wasn’t that [laughs]. I usually do either more textural things or stuff like “Ultramarine,” the piece that was in Heat, where it’s sort of rhythmic, almost half percussion. Every once in a while, another composer will ask me to play. It hasn’t happened much recently, but Transformers, that was the people who are part of the Hans Zimmer community, and I had worked on some stuff there.

Filmmaker: On Black Hawk Down.

Brook: Yeah, and Sean’s film, The Pledge. But also, I’m not a session musician. I don’t know how to read music. One of the most humiliating experiences of my life was when A.R. Rahman asked me to play on something. I think he did it because of my work with Nusrat, but I just don’t know how to play other people’s music. And I told him over and over again, “If you know what you want, I’m not the person, because I can’t do what you want. I can just do what I do.” I’ve only really played my own stuff for 40 years.

Filmmaker: What’s Zimmer like to work with in that kind of situation? It seems like he runs a huge operation.

Brook: Oh, immense. It’s great, and it’s also kind of not my thing. I really enjoyed working on Black Hawk Down, but they moved the release of the film earlier because of the Iraq war or something. It was topical, so all of a sudden it had to be done three months earlier. So, Hans got a whole bunch of people, teams really, and I was with another guitar player, Heitor Pereira, who can play anything instantly. There were a drummer and techno bass player and stuff in another studio, and then there was a cellist. I think he had five or six studios going.

Filmmaker: So he’s basically working as a director at that point.

Brook: Yeah, and composing, too. And then there was another guy, kind of an established composer, who would work in Hans’s room, like shift work, Usually I don’t work late, but we would end up going later every day, and it reached a point where one day I’m driving home, but it’s morning rush hour. I’m glad I did it and I learned a lot. I don’t really want to do it again.

Publisher: Source link

The Running Man Review | Flickreel

Two of the Stephen King adaptations we’ve gotten this year have revolved around “games.” In The Long Walk, a group of young recruits must march forward until the last man is left standing. At least one person was inclined to…

Dec 15, 2025

Diane Kruger Faces a Mother’s Worst Nightmare in Paramount+’s Gripping Psychological Thriller

It's no easy feat being a mother — and the constant vigilance in anticipation of a baby's cry, the sleepless nights, and the continuous need to anticipate any potential harm before it happens can be exhausting. In Little Disasters, the…

Dec 15, 2025

It’s a Swordsman Versus a Band of Cannibals With Uneven Results

A traditional haiku is anchored around the invocation of nature's most ubiquitous objects and occurrences. Thunder, rain, rocks, waterfalls. In the short poems, the complexity of these images, typically taken for granted, are plumbed for their depth to meditate on…

Dec 13, 2025

Train Dreams Review: A Life in Fragments

Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams, adapted from Denis Johnson’s 2011 novella, is one of those rare literary-to-film transitions that feels both delicate and vast—an intimate portrait delivered on an epic historical canvas. With Bentley co-writing alongside Greg Kwedar, the film becomes…

Dec 13, 2025