Alan Berliner on His doc, âBENITAâ

Dec 15, 2025

BENITA

Recipient of DOC NYC 2024’s Lifetime Achievement Award (as well as the 2025 Pennebaker Career Achievement Award at the upcoming Hamptons Doc Fest), the “virtuoso of essayistic documentary” Alan Berliner (Letter to the Editor, First Cousin Once Removed) returns to this year’s fest with BENITA, an unconventional portrait of an even more unconventional artist. Benita Raphan was a NYC filmmaker (and a MacDowell fellow in 2004 and a Guggenheim fellow in 2019) best known for her own short portraits of eccentric artists, from John Nash, to Buckminster Fuller, to Emily Dickinson. After graduating from the School of Visual Arts, Raphan crossed the pond to earn her MFA from London’s Royal College of Art; and would go on to spend a decade as a graphic designer in Paris before returning home in the mid-’90s to teach at her alma mater. An accomplished creative in several mediums, her works are now in the collections of the Walker Art Center as well as the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum. Raphan was also a very early pick for Filmmaker‘s 25 New Faces series, appearing on the list in 1998.

That was the public face of Benita Raphan, who was also a beloved daughter, sister and lifelong friend to many who appear as interviewees in BENITA. These include Berliner’s wife, who first introduced her husband to the talented multi-hyphenate, who in turn became his own friend and protégé. Indeed, Raphan considered Berliner her key mentor; which is why, after she took her own life at the height of the COVID lockdowns in 2021, her grieving family turned to the master documentarian to finish her last film. It was an impossible task since, as Berliner put it, “I could never duplicate the mystery and beauty that Benita always brought to her work.” So instead of completing a final act, Berliner chose to craft a collaboration, a magical cinematic conversation of sorts, between himself and his mentee. (For Filmmaker‘s print edition, Berliner wrote about making BENITA while it was in production.) Through a jam-packed archival journey comprised of films, photos, notebooks, drawings, music and more, Berliner immerses us in the ups and downs of Raphan’s life, and in his own heartfelt struggle to piece together the puzzle of her death.

A few weeks before the November 14th DOC NYC premiere of BENITA, Filmmaker reached out to the acclaimed director, whose own extensive oeuvre is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Filmmaker: So what was the process of working with this vast archive like? How did the film change over various cuts?

Berliner: As with all of my films, BENITA began as a hunch, an intuitive feeling, and a leap of faith. This is the fourth portrait I’ve made, each centered on a relatively unknown person that most people would agree is an unlikely candidate for biographical attention. Each of my portraits has been built upon a thorough excavation of my subject’s personal archive, which I use to try and tell a story that reckons with the poignancy and meaning of a life lived.

Benita may not have left a note when she took her life, but her archive was a kind of trail — what I call a “filmmaker’s trail” — filled with her films, outtakes, videos, photographs, sounds, music, notebooks, journals and enough digital material to fill 40 hard drives. I spent a year going through all of it, patiently, carefully and diligently.

My narrative approach towards Benita and her work is centered on my role as her filmmaking mentor – someone she was open and honest with about the celebrations and struggles of her career, while also inviting my candid feedback about her films. Weaving this perspective throughout the film eventually became a storytelling thread, encouraging me to make the film increasingly personal over the course of editing.

In total, I spent four years immersing in the universe of material that Benita left behind. That kind of dedication facilitated a kind of transcendent bond with Benita, allowing her creative spirit to enter the process in mysterious ways, and ultimately leading me to conceive of the film as a kind of collaboration. Over time the nature of our collaboration – in particular my use of her handwritten notebook and journal entries – expanded the storytelling dynamics of the film, in essence giving Benita a chance to participate in telling her own story. At various points throughout the film Benita’s words onscreen address me directly, add her personal commentary to various subjects, and on occasion allow her to speak to the viewer.

Filmmaker: How did you decide what from the archive to include – and what not to? Were you concerned with not revealing anything you think Benita might have preferred to remain private?

Berliner: My decisions on what elements of Benita’s archive to use in the film also evolved over time. I knew that Benita trusted me. I also knew that she respected the kinds of personal films I made and valued their honesty. I think it was an approach and a creative ethos she aspired to in her own filmmaking.

Throughout the process I was extremely moved to find Benita’s firsthand account of her struggle with depression and anxiety in her journals. But it wasn’t until I discovered an unlabeled QuickTime video that Benita recorded of herself saying she was going to scrap her work in progress film about canine cognition and instead make a film about the impact that COVID was having on people with mental health issues that my ideas for the film would finally take shape. As Benita’s mother Roslyn says in the film, “It was like a coming out as who she was and what she’s been living with all these years…There was no longer a need to hide anything.”

That discovery gave me a kind of permission to follow through on Benita’s intention and allow the film to explore the relationship between mental health and creativity. It also enabled me to introduce COVID as a character in the film.

Every choice I made was guided by an aspiration to tell the story of Benita’s life in a way that could give new meaning to her death. I embraced the power and poignancy of Benita’s own words, written by her own hand, with her occasional funky grammar and spelling mistakes; words that came from Benita’s heart and soul. Not using them would be like painting a portrait without the color black, dark grays or brown.

Of course, doing so is also a risk I take, and I suppose that’s why you’re asking the question. It’s my hope that once it’s revealed that Benita had contemplated making a personal film about her mental illness, viewers will understand why I felt comfortable including her emotionally charged words inside the film. Ironically, had Benita not taken her life, and followed through on her new film idea, I would have been her creative advisor. You can be sure I would have encouraged her to be as honest as humanly possible.

It’s also important to remember that everything I use in the film comes from the archive I was given by Benita’s family.

Filmmaker: Besides the sheer amount of material, what were some of the biggest challenges you faced? Were they different from (or similar to) hurdles you’d encountered with your prior work?

Berliner: The three portraits I made prior to BENITA were all about family members: my grandfather Joseph, my father Oscar, and my cousin Edwin. This is the first film I’ve ever made about someone I’m not related to. It’s also the first film I’ve ever made about a woman.

When making a film about a family member there’s an unspoken assumption that whatever I learn about them, from them — whether it’s genealogical, genetic, familial or cultural is something I’m also learning about myself. Sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse.

My connection to Benita is based on a different set of assumptions. We were friends. We were both filmmakers – experimental documentary filmmakers. Artists. Benita thought of me as a mentor, a creative advisor. She trusted me. I believed in her.

Making this film was a chance for me to take a deep dive into the life, the work, and the death of an artist and filmmaker with whom I had a special relationship. Benita was the first person I’ve ever known personally who took her life. It’s a normal reaction to respond to the shock of such a profound act with a lot of second-guessing, thoughts about what I could have said or done that might have made a difference; and with memories of unfinished conversations, conversations never had, regrets, and countless questions that will never get answered.

Filmmaker: Did you consult with Benita’s friends and family as you developed the project? How do her loved ones feel about the final film?

Berliner: I learned a long time ago to never show an unfinished film to someone who’s in the film or has a deeply invested — and complicated — relationship to the subject of the film. You leave yourself and the film open to much second-guessing; and to a potential plethora of emotionally confusing responses that are often difficult to deal with, especially when you’re still in the process of completing the film.

Benita’s mother Roslyn and her sister Melissa were the ones who initially approached me, and who gave me all the elements I used to make the film. I interviewed Roslyn several times; Melissa chose not to participate in the film. In all I spoke with 14 of Benita’s friends and colleagues throughout the course of making the film.

There’s no question that people who knew Benita, especially her family, will experience an avalanche of powerful feelings after seeing the film. It’s also to be expected that they’ll need time to process all of it.

In the end, I’m happy that Roslyn and Melissa will see the film for the first time at the upcoming DOC NYC premiere. I truly believe it’s important for them to see the film with an audience; to see that the story of Benita’s life and her death (as best as I can tell it) no longer belongs to them and no longer belongs to me, but is now part of a much broader conversation.

I want the film to imbue Benita with a legacy, a universal resonance. To become an experience that audiences can project upon, learn from and empathize with; and one that can provoke them to ponder their own lives (or the lives of those they love) through the prism of Benita’s story.

In many ways, though it was unspoken, this was something I thought Benita’s family was hoping for when they agreed to allow me to make the film in the first place.

Filmmaker: How has making this film — and going through the experience of losing Benita — ultimately changed you as a filmmaker?

Berliner: Making this film made me look at myself differently. It became a mirror to my own work, to my own creative process, to my own strengths and weaknesses. It was a daily reminder of human fragility and mortality, and a meditation on the meaning of a life lived. And if I did it right, I wanted the film to touch each viewer with an awareness of these existential uncertainties and questions in their own lives.

The journey of the film made me appreciate how my own problems and challenges have, over time, become my “strengths.” That everyone has flaws, foibles, difficulties and challenges that shape who they are and how they do what they do. I now see my film Wide Awake (2006), a personal story about my chronic insomnia, in a new light: how I’ve learned to turn the pain and anxiety of a sleep disorder into creative fuel.

In a similar vein, making BENITA required a great deal of obsessive energy on my part, making me more deeply aware of how my capacity for obsession has become a “secret power” throughout my life — and strengthened the muscles of passion and commitment along with it. That art, in all its myriad forms, is a safe space to work through one’s issues and struggles, and transform them into positive, purposeful and sometimes even “healing” work for both the artist and those who experience their work.

An important insight of making this film was seeing how Benita’s choice of film subjects was often an expression of her unconscious mind. Many of her films were about people with emotional and/or psychological problems who overcame them to become creators, innovators and artists — a mirror to understanding herself.

Seeing Benita’s body of work through this kind of lens made me reflect on my own unconscious choices as a filmmaker. In 1980 I put an image of a family of four sitting at a kitchen table inside a montage of my short film City Edition. I now see that decision as a reminder, a seed planted, that I would one day need to deal with the anguish of my parents’ divorce and its impact on my life. I used that same image 16 years later in my film Nobody’s Business (1996), where I confronted the pain of my family dysfunction head-on. Now almost 30 years later, that seed has grown into a theme that’s been woven into many of my films.

My experience with a cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment in the middle of making BENITA – and the physical and emotional toll that came with it – also made me empathize with Benita’s struggles; and gave me a new, and unsettling, perspective on her decision to take her life rather than live in so much pain.

Publisher: Source link

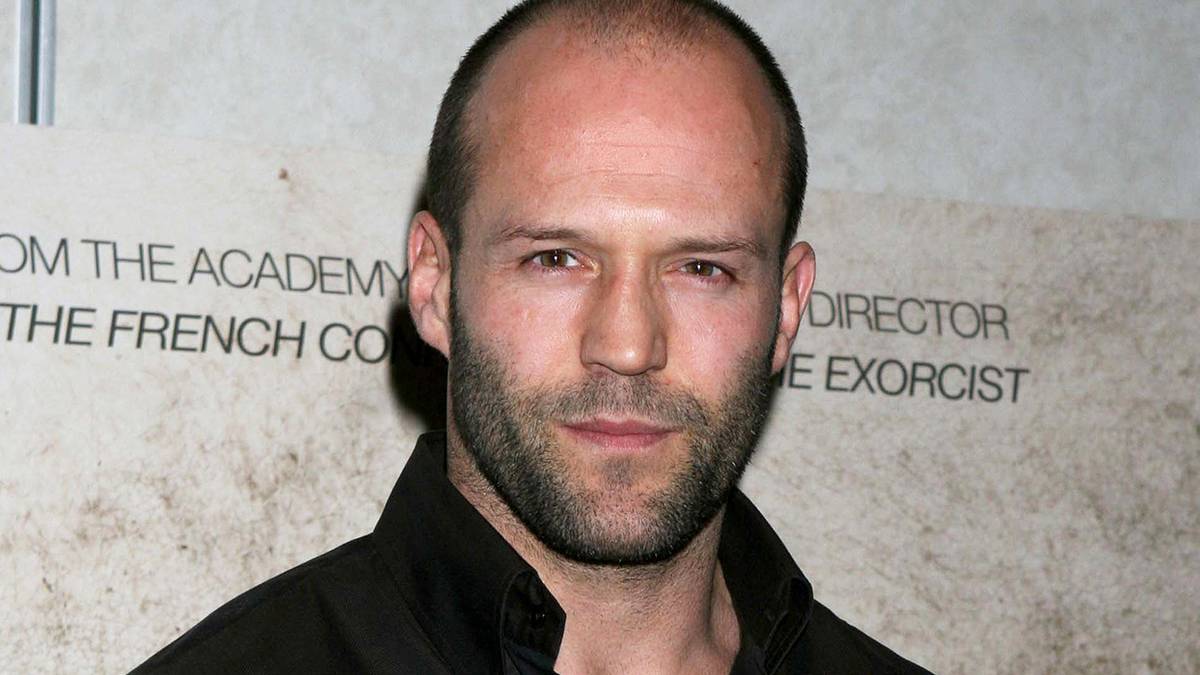

The Running Man Review | Flickreel

Two of the Stephen King adaptations we’ve gotten this year have revolved around “games.” In The Long Walk, a group of young recruits must march forward until the last man is left standing. At least one person was inclined to…

Dec 15, 2025

Diane Kruger Faces a Mother’s Worst Nightmare in Paramount+’s Gripping Psychological Thriller

It's no easy feat being a mother — and the constant vigilance in anticipation of a baby's cry, the sleepless nights, and the continuous need to anticipate any potential harm before it happens can be exhausting. In Little Disasters, the…

Dec 15, 2025

It’s a Swordsman Versus a Band of Cannibals With Uneven Results

A traditional haiku is anchored around the invocation of nature's most ubiquitous objects and occurrences. Thunder, rain, rocks, waterfalls. In the short poems, the complexity of these images, typically taken for granted, are plumbed for their depth to meditate on…

Dec 13, 2025

Train Dreams Review: A Life in Fragments

Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams, adapted from Denis Johnson’s 2011 novella, is one of those rare literary-to-film transitions that feels both delicate and vast—an intimate portrait delivered on an epic historical canvas. With Bentley co-writing alongside Greg Kwedar, the film becomes…

Dec 13, 2025