âMy âJawsâ Obsession Had No Boundariesâ: Kleber Mendonça Filho on âThe Secret Agentâ

Dec 29, 2025

Wagner Moura in The Secret Agent (photo by Victor Juca)

Kleber Mendonça Filho has never been shy explicating how personal memories have seeped into his professional work. Born and raised in Recife (capital of the Brazilian state of Pernambuco), the filmmaker has consistently dived into its history and, in doing so, his own history as well. While technically a narrative (featuring a remarkable cast led by Wagner Moura), The Secret Agent is also a movie about tumultuous events in and around the filmmaker’s hometown. Anyone who spoke out against the military dictatorship’s brutality was relentlessly harassed, spied on and, in some instances, murdered.

An adolescent when these events unfolded, film-critic-turned-filmmaker Mendonça Filho uses The Secret Agent to explore both his obsessions with the period and adoration for its popular moviegoing culture. In his Cannes coverage from earlier this year, Vadim Rizov observed that “The Secret Agent is something like Mendonça Filho’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, an immaculately immersive and visibly expensive reconstruction of the filmmaker’s formative years.” Like Tarantino’s film, The Secret Agent uses historical events as its framework and moviedom as its lifeblood. But where Tarantino was enamored with revisionist history as a means of righting the past’s wrongs (the murder of Sharon Tate), Mendonça Filho uses cinema to draw us into the subconscious of the Brazilian people.

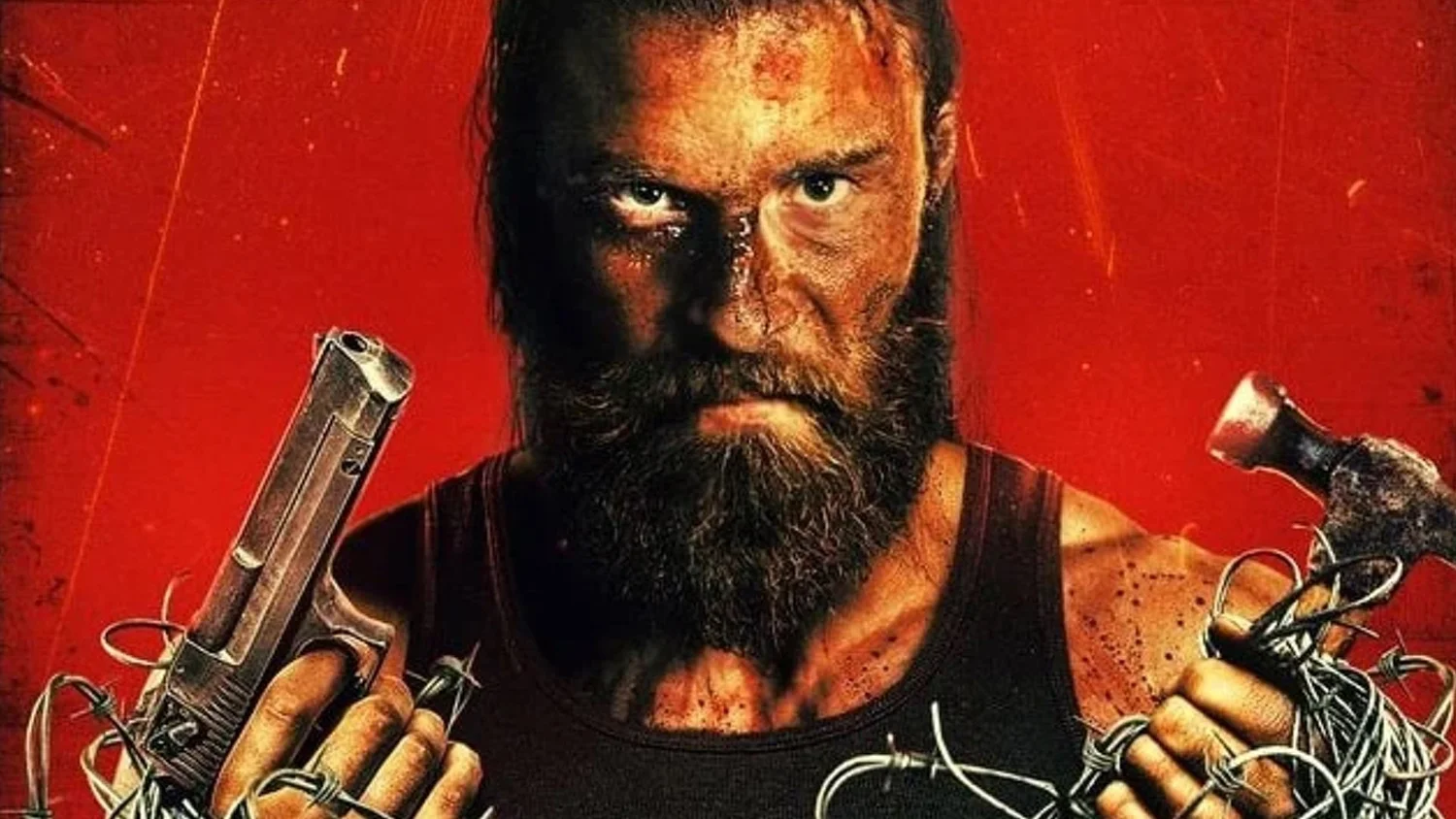

A widower and former scientist turned enemy of the state, Armando (Moura) is desperate to reunite with his nine-year-old son Fernando, a young boy living with his grandparents who continuously begs his grandfather (Armando’s father-in-law, a projectionist at Cinema São Luiz) to take him to see Jaws (1975). At the same time, a dead shark with a human leg protruding out of a gash in its stomach has washed up nearby, drawing interest from the local authorities. While shark attacks have been frighteningly common in Recife since the 1990s, hardly any were reported to have taken place in the 1970s. Has the hype around Jaws begun to mirror the very narrative we’re watching? Right down to its surprising concluding scene, The Secret Agent is a film in which everything unexpectedly begins to double up, which becomes clear as early as when a cat with diprosopus makes a surprise cameo.

The Secret Agent is currently in theaters courtesy of NEON.

Filmmaker: When we last spoke for Pictures of Ghosts, you mentioned that while working on that film, you “began to find the information and atmosphere needed for the script that I’m actually going to shoot later this year, The Secret Agent, a fiction script [I wrote] that takes place in 1977. Researching Pictures of Ghosts made me more open to that script, I think, and then when I went back to it, I kept thinking of Pictures of Ghosts. It’s like they had an exchange program between them, suggesting incidents and bits of history for the other’s [development].” I thought about that a lot while watching your latest film, how the two are in conversation with one another.

Mendonça Filho: Yes, it was a beautiful process, and Pictures of Ghosts introduced me to many of those materials. It was probably the closest I have ever come to time-traveling because, in looking at my own archive, if you were to add up all the years—from my time at university and then later into my 20s, 30s and 40s—I still have a lot of photographs and video from the late 1980s and early ’90s. I’ve been photographing and shooting Recife for so long that it almost felt like I had been preparing and researching to make this film for 35 years. My [process] for shooting in Recife really came from knowing where to put the camera. With a good budget, of course, you can bring in cars that are specific to the period and incorporate fancy visual effects and all of that, but it’s very much about buildings and the way the city photographs.

Pictures of Ghosts put me in the right mindset to finally write the script for The Secret Agent, and as I was writing it, I was still finishing Pictures of Ghosts. It was the perfect combination [of projects], as I think one film leads into the other. This has been the case throughout my career. Neighboring Sounds (2012) is very different from Aquarius (2016), but it’s through Neighboring Sounds that you can see where Aquarius comes from. You can tell that it was the same person who made both films, because they overlap in interesting ways. Maybe Bacurau (2019) is the outlier of my [filmography], but there is a museum [in the film] where some secret is being kept inside and then there’s a little museum in Sebastiana’s house [in The Secret Agent], so each of my films connect in interesting ways. But yes, Pictures of Ghosts really is the film that led me to The Secret Agent.

Filmmaker: In 1977, you were probably right around the age Fernando is in the film?

Mendonça Filho: Yes, in ’77 I was nine.

Filmmaker: I was curious about your relationship to Jaws then, around the time of its theatrical release in Brazil. I imagine that would—as The Secret Agent depicts via Fernando’s perspective—dominate the attention span and every waking moment of someone of that age. Did this stem from a personal experience?

Mendonça Filho: Jaws was first released in Brazil at Christmas of 1975. I was already a very young cinephile by then, and my mother supported my young cinephilia. We would go to the cinema many, many times. But back then—and this is something that you can see in Pictures of Ghosts—the cinemas downtown were not only cinemas, but almost like outdoor exhibits of movie posters and lobby cards. So not only did I watch films at the time, but the movies being displayed in the windows outside also played a very big role in my desire for more cinema. One of these films was Jaws because, while I wasn’t old enough to see the film when it first came out in 1975 (as it was rated-14), the film was always present in the shop windows; it was a very popular film. It kept returning to the cinemas in special re-run [engagements], and I was obsessed with the poster which everybody knows, the phallic symbol of the monster coming from below to catch the woman swimming above. Yes, I am Fernando in the film, and my Jaws obsession had no boundaries. Something that is rarely remembered these days was that Jaws began a fever of animal-monster movies, of nature-getting-its-revenge films, like Orca (1977), which I did see in theaters at the São Luiz Cinema. There was also Irwin Allen’s The Swarm (1978)…

Filmmaker: Tentacles (1977) with John Huston was another one.

Mendonça Filho: Tentacles, yes, and Piranha (1978) from Joe Dante, of course, which I could not see, as it was rated-16, so I only saw it [later]. But I had lunch with [executive producer] Roger Corman in Bordeaux about five or six years ago and was able to tell him that as a young kid, I saw the poster for Piranha and was completely impressed. All of these things are part of who you are as a cinephile—not only the films you see, but the films’ posters that stimulated your mind as a young person. Of course, these days you learn about new films via your smartphone, which is just not the same thing.

Filmmaker: In The Secret Agent, I noticed a mounted poster outside of the São Luiz Cinema for Bruno Barreto’s Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands (1976) [which starred Aquarius and Bacurau co-star Sônia Braga].

Mendonça Filho: Yes.

Filmmaker: I wondered what a nine-year-old might think by seeing that poster.

Mendonça Filho: Well, it was a huge hit in Brazil. For 35 years, it was considered the Titanic of Brazil, by far the biggest box office attraction. But it was rated-18, of course, so I couldn’t [see it], but I remember adults talking about Dona Flor quite a lot at the time.

Filmmaker: You’ve previously noted how a reference for the opening sequence in The Secret Agent, in which Armando, before driving into Recife, stops at a desolate gas station and comes across a freshly murdered corpse decaying right in front of him, was Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright (1971). It’s a fascinating reference, as I could almost feel the extreme, dry heat coming off the screen in your film, both due to where and how the scene was shot.

Mendonça Filho: Wake in Fright is a film I like very much because you don’t really anticipate how savage some of the situations are going to be. Unless we are talking about the kangaroo sequence, it’s not even a film where someone is violent against somebody else. The film basically just shows “behavior,” but it’s very rough, masculine behavior, and then there’s the environment and that little town and the bright sunshine and the heat and sweat, etc. Discussing references is really hard for a filmmaker because you, as a cinephile, have your own relationship to movies, right? Some people look at a film which features a scene where someone is taking a shower and go, “oh, just like in Psycho!” Not necessarily [laughs]. But Wake in Fright is a really interesting reference for this film, and, of course, Brazilian cinema from that era being another [reference], especially Iracema – Uma Transa Amazônica (1974) from Jorge Bodanzky and Orlando Senna, which I’m planning to show at this special program at Film at Lincoln Center in January. There is something about the images of the film, from the 1970s, which have a lot of texture to them, the texture of reality. This is something I really dislike about many modern films. They are so clean, from the high-quality lenses to the 8K resolution to the use of green screen. Just because we can, doesn’t mean [we should]. Rather, why don’t you go and shoot on location? “Oh, well, because nobody will notice.” Yes, I will. I will notice that it looks like shit, you know? So, we actually went to the Outback to shoot that gas station sequence, and we had the flies and heat and old Panavision, anamorphic lenses…

Filmmaker: And vintage, broken-in equipment can create, subconsciously or otherwise, its own kind of visual texture.

Mendonça Filho: I think it’s an interesting case of subconscious [mixed] with fact. You can really see it, but yes, probably for most people, it’s subconscious. I grew up watching great films shot on Panavision anamorphic [lenses], and it really did something to my brain. I really like the idea of composing those shots and of knowing that that old glass [lens] has been used in the making of so many films. One of the lenses we used, I think, was used on [John Boorman’s] Deliverance (1972).

Filmmaker: Really?

Mendonça Filho: Yes, so it kind of plays with the whole idea of history, images from history.

Filmmaker: Where did the inkling to include an isolated sequence about The Hairy Leg come from? Were its origins something you read about in the local newspaper in 1977, as characters do in the film?

Mendonça Filho: “The Hairy Leg” is something I remember from childhood, yes. It was an urban legend, and I remember a nanny telling me, “if you don’t behave, ‘The Hairy Leg’ will come and get you.” I also remember my mom reading about it in the newspaper, exactly as Tereza reads about in The Secret Agent. It was an urban legend developed by two journalists who were always dealing with censorship, so they came up with this code, “The Hairy Leg.” But what The Hairy Leg actually was was police beating people up in the park, especially the gay community (and all of the “other degenerates”) who were making out, having sex and fucking. That became a phenomenon. It was all over the newspapers and cartoons and radio programs. When I was doing research for Pictures of Ghosts, I found the actual articles that came out at the time [about The Hairy Leg] in the local paper. This was not the Literary section on Sunday—no, this was in the Metro section. That should give you an idea of how crazy and transgressive the city is! One way of facing censorship is by showing how ridiculous it is, i.e. “Let’s publish a story about ‘the zombie leg.’” The public reaction was crazy. I’ve always wanted to use it and thought [The Secret Agent] would be the film.

Filmmaker: And for that sequence I believe you used stop-motion animation to visualize its movements? Puppetry?

Mendonça Filho: The stop-motion effects for the leg moving around the city were created in Holland. I shot empty plates with the actors/victims and the [first-person] camera movement, knowing that later in post-production, we would add in the hopping, jumping leg. There are also some shots with the leg that were performed by an assistant whom we tasked with attacking the actors with a prosthetic leg. Imagine how funny that was! And while the stop-motion leg was about this size [Mendonça Filho using his hands to indicate a size of a few inches], the puppets on set were bigger, essentially life-size.

Filmmaker: The past and present converge in really fascinating ways in the film, and I know some of that is derived from a personal place. The archivist character in the present day, Flavia, is, in some ways, a tribute to your mother. I was curious about your mother’s relationships to oral history, to interviews and recordings, and the idea of simultaneously bringing the past and present together via changing technology.

Mendonça Filho: I think cinema is an amazing tool in which to analyze time. You know, you could have an unbroken shot of two people talking for seven minutes, and so [laughs] it ends up being a documentary of those seven minutes. It’s a real-time document of two people talking. It could be fiction or documentary. I’m completely fascinated by that. My mother worked with recordings on tape, and just recently, as I was writing the preface for the book that’s coming out in Brazil which contains the script for The Secret Agent, it dawned on me that, in a strange way, she might have been making a form of cinema with her recordings. She [conducted] many great interviews with wonderful Brazilian cultural figures, writers and filmmakers, [in the 1970s] and to hear those recordings really took me back, in a strange and melancholic but also beautiful way. I would look at the date of a recording and think, “Wow, I was only 11 at the time. What was I doing on the day she was doing this recording?” The whole thing just plays with my mind.

I think it’s fascinating that these people were living their lives in 1977 and, like Wagner’s character Armando, trying their best to survive. When he meets with Elza at the cinema to discuss [obtaining fake passports to leave the country], they are discussing matters of life and death, but actually [laughs] there is somebody in the future who will be listening in on their very conversation [Elza records the conversation on cassette tape]. It’s like our conversation now—if if survives, somebody will be listening to us in the future. I’m fascinated by that. That is cinema itself. I spent years working as a critic and would always have a little mini DV camera with me, placing the camera here or there to interview filmmakers who would allow me to do so. It [became] a little documentary, 80 minutes long, called Critico, back in 2008. I find that, as the years pass, that film becomes more and more interesting because of a number of things: its image quality, the people being interviewed, the people who have since died and how cinema itself was evolving, changing, improving, or getting worse, depending on our discussion. Making that film was the first time I realized that the work of my mother had a strong influence on what I do for a living.

Filmmaker: Armando’s relationship to the memory of his own mother and his relentless pursuit of official documentation of her existence [as a teenage homemaker, the young indigenous woman was taken advantage of, eventually becoming pregnant with Armando] is also a beautiful way to illustrate the need for some acknowledgement of history, in this case, a personal one.

Mendonça Filho: That’s true. There’s a very intelligent piece about the film in Brazil’s biggest newspaper today, where an academic wrote about something no one had yet mentioned. He wrote that at the end of the film, Fernando tells the historian, Flavia, that, when he was a kid, he had nightmares about Jaws. But then, once his grandfather finally took him to see the film, the nightmares stopped. In the academic’s interpretation, he saw this as being about how the country of Brazil deals with memory. If Brazil doesn’t fix the memory problem, it will continue to make the same mistakes and thus have more nightmares. I thought that was an interesting insight.

Publisher: Source link

A Snake-like Light Skewering of the Hollywood Ouroboros

The re-adaptation of existing IP has become such a ubiquitous practice in Hollywood that the industry has started eating its own tail, and filmmakers are referencing the IP itself in increasingly metatextual ways. See: Scream V and VI. See: The…

Dec 31, 2025

Five Nights at Freddy’s 2 Review: Darker, Deeper, But Uneven

Emma Tammi’s Five Nights at Freddy’s 2 arrives with both the burden of expectation and the advantage of familiarity. Following the massive success of the 2023 film adaptation, this sequel sharpens its focus on the haunted legacy of Freddy Fazbear’s…

Dec 31, 2025

Andrew Rannells’ Grisly Holiday Murder Mystery Wraps Up 2025 on a High Note

Editor's Note: The following contains spoilers for Elsbeth Season 3, Episode 10.How far would you go to see your child's dreams of being a star performer come true? How about if your own dreams of the same never did, and…

Dec 29, 2025

Against The Odds, Scott Derrickson’s Smart Sequel Deepens The Original’s Chills

When “The Black Phone” landed in theaters in the summer of 2022, it performed better than many people expected. Having already screened at several festivals, word of mouth from critics and early audiences was good, and a twice-delayed release heightened…

Dec 29, 2025