DP Michael Bauman on âOne Battle After Anotherâ

Jan 12, 2026

Leonardo DiCaprio and Benicio Del Toro in One Battle After Another

For the first time since 2002’s Punch-Drunk Love, Paul Thomas Anderson has made a movie with a contemporary setting. To do so, he used a film format dormant for the last half century.

Anderson’s One Battle After Another continues a resurgence of VistaVision that now includes The Brutalist and Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things and Bugonia. The format, which uses 8-perf 35mm traveling through the camera horizontally rather than vertically to create a larger negative, gained popularity as a non-anamorphic widescreen alternative in the mid-1950s. It was used for everything from Biblical epics (The Ten Commandments) to musicals (White Christmas) to Alfred Hitchcock thrillers (Vertigo and North by Northwest). Marlon Brando’s 1961 Western One-Eyed Jacks marked the last major Hollywood film of the era to use VistaVision as its main production format, though Vista did see a resurgence beginning in the late 1970s for special effects work.

One Battle After Another cinematographer Michael Bauman, a former longtime gaffer who’s worked with Anderson since The Master, spoke to Filmmaker about resurrecting the format.

Filmmaker: Looking over your credits, I noticed that you worked on Darren Aronofsky’s student film Protozoa at the American Film Institute, which Matthew Libatique shot.

Bauman: Yeah, we were all in the same class together at AFI. Matty and I have done tons of jobs together since then. He’s my oldest friend in L.A. It’s good that him and Darren have kept that relationship going for so long too. It’s pretty incredible.

Filmmaker: Any memories stand out from that short?

Bauman: Even back then, Darren was doing crazy stuff. When Requiem for a Dream came out, I was like, “Of course.” That short was just a bunch of 21-year-olds running around trying to make a movie. It’s crazy that it was 30 some years ago.

Filmmaker: Have you officially hung up whatever it is that a gaffer would hang up—your gaffer glass, maybe? Do you consider yourself a full-time DP now?

Bauman: I’d say I’ve probably moved on, but we’ll see. Who knows? Things change all the time. It wasn’t ever really a thing of like, “Okay, I’m only going to do this now.” It just kind of evolved this way. To me, it’s always been about interesting projects. Would I do a gaffing job again? If it was a really unique project, I’d totally be interested if it’s the right fit at the right time, but I certainly enjoy being a cinematographer.

Filmmaker: Was The Master your first Paul Thomas Anderson project?

Bauman: Yeah.

Filmmaker: He tested VistaVision all the way back then. Were you on board for that part of prep?

Bauman: Yeah, I actually still have photos from of our initial tests. We lined up a 35mm, a 65mm and a VistaVision camera. There was a section of the script that Paul was looking at doing in large format and we ended up settling on 65mm for that section. Then, of course, he loved it, and we ended up shooting almost the entire movie in 65mm. [laughs]

Filmmaker: I’ve been reading about this Beaumont VistaVision camera you used, but I couldn’t find much info about them. Do you know what era those are from?

Bauman: To be honest, I don’t know a ton of history about that specific camera. The history of Vista and how it came to be is so fascinating, though, how the tech was driving things at the time just to get people into the theaters. When VistaVision was in its heyday in the fifties and sixties, the cameras were much, much larger. The Beaumont was the most portable version of Vista, and I still think that remains true. The Wilcam would be a close second, which is what Robbie Ryan did Bugonia on.

Filmmaker: Did you go back and watch any of those Hitchcock VistaVision movies or One-Eyed Jacks or anything from that era?

Bauman: I saw a few things in VistaVision. What was interesting was that with Paul, you watch film dailies. A lot of times, even if you shoot film, you’ll get digital files [for dailies]. On this, we had a traveling projection booth with two Super 35 projectors and one VistaVision projector. The biggest challenge was finding projectors that would be up to snuff that could run a lot of footage through. One day when we were at dailies, our editor Andy [Jurgensen] was like, “I’ve got a surprise for everybody.” Somebody from Warners had found an original negative roll of North by Northwest in VistaVision, which was framed for 1.85 even though [VistaVision] cameras shoot 1.5. It was a scene where they’re in front of Mount Rushmore that they shot on stage, and you could see the top of the backing and parts of the stage. It was cool and looked gorgeous.

Filmmaker: I’ve heard some of the DPs who have used VistaVision recently talk about how it’s difficult to shoot sync sound with the cameras because they’re so noisy. Obviously, they shot those 1950s and 1960s VistaVision movies with sync sound, but some of those cameras back then were in huge soundproof blimps. I’m assuming the contemporary sound problems come from the cameras being liberated from those cumbersome housings. How did you deal with the problem of getting usable sound?

Bauman: We basically designed our own blimp. The Beaumont is designed to sit on a tripod and just be like, “Okay, give me a great Vista shot,” and it works fantastic like that. However, as soon as you have to start moving the camera [it becomes difficult]. So, it was like, “How small of a blimp can we make so we can actually use sync sound?” We also shot tests without the blimp to see what Skywalker Sound could do, because there’s all these new post processes that could potentially help out depending on the application. Bugonia basically shot on stage, but we didn’t. We only had one or two days where we shot on stage. Most of the movie was all practical locations. So, we had to try to find a way to make the blimp work. One of the problems was you can only put a certain amount of lens motors in the blimp. A lot of times I’m pulling iris and doing exposure changes, but you can only put one motor on it and our 1st AC Sergius Nafa needed to have his focus motor. So, you couldn’t do focus and iris at the same time. We did still use the housing several times in the film, for example in the scene with Willa in the bathroom where the pager goes off for the first time and Regina Hall appears in the mirror.

Filmmaker: You used Steadicam in the movie, but I’m guessing the blimped version of the camera was too bulky to go on there?

Bauman: It was. In all the set photos where the blimp is out, no one is smiling. [laughs] It was a whole deal. What we ended up doing was developing something like an Easyrig that we’d use with our dolly grip John Mang’s cart. That cart has been on a million movies. It should have its own IMDB page. It was a lot of experimentation and figuring out things like how [different ways of moving the camera] affected the magazine, because weight shifts sometimes can cause the mag to jam. It was complicated.

Filmmaker: How much did you end up having to shoot on Super 35?

Bauman: It wasn’t that much. Most of the Super 35 stuff was for two reasons. One, if it was really critical for sound. The other thing was that since a thousand-foot Vista mag takes film twice as fast, you only have about five minutes tops, maybe four and a half minutes. Sometimes we’d have a longer dialogue scene, so we’d use Super 35 for performance reasons. The other problem we discovered is the Beaumont camera doesn’t like it if you have a full thousand feet. You really do better at 800 feet, which means you actually only have four minutes of shooting time [per mag]. The reloads also take a while on Vista; on Super 35, you can reload the camera in under 20 seconds.

Filmmaker: Did Kodak specially make 800-foot rolls for you or did your loader have to go in and trim them?

Bauman: Yeah, our loader Jackson [Davis] had to go in and cut them all down.

Filmmaker: I’m assuming for things like the crash cams you weren’t strapping one of those VistaVision cameras in there.

Bauman: No. [laughs] We only had three Beaumonts that were reliable and the one we got from [actor/cinematographer] Giovanni Ribisi was really the best one. Then we had two Panavision Millennium XLs [for Super 35]. That was our main package and sometimes we’d use Arri 235s or 435s for things like crash cams because they are double pin registered and more reliable.

Filmmaker: When you got into the grade, did you find you were making less adjustments or different types of adjustments than when you’ve done DIs on projects shot digitally?

Bauman: Well, the first thing is that for Paul, everything is about [doing things] photochemically as much as possible. It makes it interesting because a lot of times as a cinematographer you can sit there and shoot something and you’re like, “Okay, cool, I can go in later and do all this amazing stuff that you can do now in a post suite.” Paul doesn’t operate from that space. You put as much energy on the day as you can toward getting it as right as possible. There is a shot in the film where Tim Smith shoots Lockjaw [from a moving vehicle]. When we shot that we had so much light pumping in on Tim. You have to be right on your exposures with Paul because you don’t have the luxury of being like, “Okay, I’m going to take that down and fix this later.” So, I was like, “We might have to [power] window Tim Smith.” And Paul is like, “Really? Come on.” I was like, “Okay, so we’re not going to do that.” [laughs] Our VistaVision prints were actually off of original negative, so there wasn’t a DI in that process. So, in the five theaters that played the film in Vista, all the VistaVision stuff is off of the original negative. They even put less visual effects in on the Vista prints because they didn’t want to scan stuff and then film it out unless it was absolutely necessary.

Filmmaker: I had initially assumed that your options for lenses were limited when you shot VistaVision, but then I read the American Cinematographer story on the film and it says you had something like 60 sets to test. What were some of the lenses you went to the most?

Bauman: There’s a set of lenses that they call the GW’s because they’re based off of glass that [The Godfather and All the President’s Men cinematographer] Gordon Willis had. We’ve used those since even before Phantom Thread. They’re made by Panavision. Paul’s always going to go Panavision because him and [Panavision’s senior vice president of optical engineering] Dan Sasaki have had a relationship for a long, long time. When you’re shooting film you’re generally going to be in Panavision’s world. We carried four 50mm lenses with us because each 50 had a different characteristic to it. One might have lower contrast, one might flare more, one might be sharper or have more resolving power. It really depended on what the application was per shot. We had a lot of different lenses and focal lengths. Dan was constantly sending updated stuff, and it was tough for Sergius because he’s like, “Dude, I don’t even know if this thing is calibrated right. I’ve got to check this before I put it up.” We’d have lenses come where [the barrel markings] were not even engraved. It would just have tape on it with the focal marks. Sometimes you’d check out the lens and be like, “How does this one resolve on the sides? Oh, it doesn’t [laughs], but that’s actually kind of cool. Let’s use that.”

Filmmaker: What did you use this crazy 1200mm Canon lens for? That thing looks like it’s about three feet long. Was that shot of Sean Penn walking over those rolling hills toward the end done on that lens? Such a cool shot.

Bauman: Yeah. We were trading that lens with Sinners. It was playing back and forth and then they’d have to modify it for our needs. We also used it inside the mission where Willa finally meets Lockjaw for the first time. There’s a shot where he says, “Come closer,” and then we cut to her. That was on the 1200. It was an interesting piece of glass. It had a minimum focus of something stupid, like 40 feet. [laughs]

Filmmaker: Tell me about the Christmas Adventurers Club meeting room.

Bauman: That was one of our few sets that we built on stage. Florencia Martin, the production designer, and Paul had been talking and one of the things they wanted to incorporate was this diorama. I took that as, “Christmas Adventures have so much juice that they can control man or beast.” That’s their view of the world. I think we used Vista for the entrance shot, but I think most of it was Super 35. We lit it with top light and just a little bit of frontal fill, and the diorama’s primarily featured in the background, so you could easily run multiple cameras. That’s not something Paul normally likes doing, but sometimes you do it out of necessity. We did it a few times when Bob is on the phone for the second time with the guy up in sensei’s apartment because Leo was just on a tear. Then when we shot the other half of that conversation, it was the same thing. You’d run a couple cameras just because the improv was great, and you didn’t want to not catch any of that.

Filmmaker: One of my favorite images from the film is a rooftop silhouette as DiCaprio’s trying to escape from sensei’s apartment.

Bauman: Those guys [running on the roof alongside DiCaprio’s character] were just local talent and we had a stunt team also jumping with them. It was like, “Okay, how do we show that there’s a huge battle going on underneath (this roof) on the streets and it’s getting really out of control?” We kept it really simple. It was just one condor with a backlight, then smoke and fire from below and [camera operator] Colin Anderson and [key grip] John Mang racing as fast as they could with the camera. That’s just a really beautiful, strong image and it’s one of my favorite images from the movie.

Publisher: Source link

The Housemaid Review | Flickreel

On the heels of four Melissa McCarthy comedies, director Paul Feig tried something different with A Simple Favor. The film was witty, stylish, campy, twisted, and an all-around fun time from start to finish. It almost felt like a satire…

Jan 30, 2026

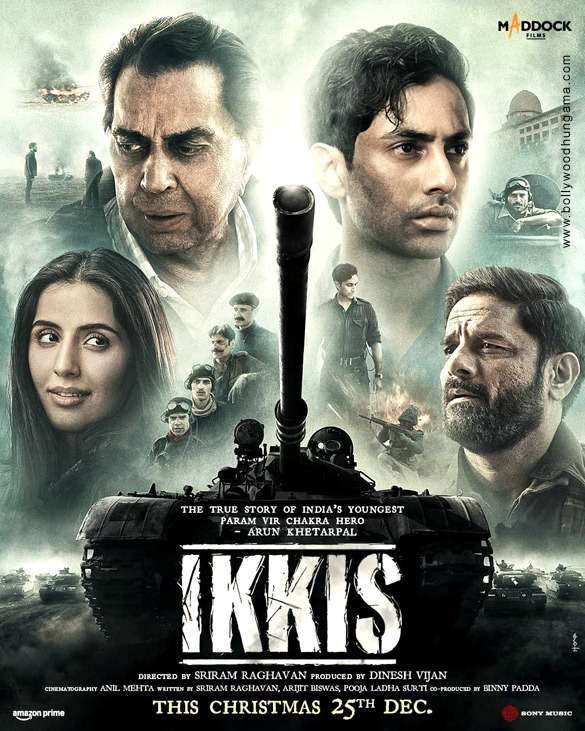

The Legacy Of A War Hero Destroyed By Nepotistic Bollywood In “Ikkis”

I have seen many anti-Pakistani war and spy films being made by Bollywood. However, a recent theatrical release by the name “Ikkis”, translated as “21”, shocked me. I was not expecting a sudden psychological shift in the Indian film industry…

Jan 30, 2026

Olivia Colman’s Absurdly Hilarious and Achingly Romantic Fable Teaches Us How To Love

Sometimes love comes from the most unexpected places. Some people meet their mate through dating apps which have gamified romance. Some people through sex parties. Back in the old days, you'd meet someone at the bar. Or, even further back,…

Jan 28, 2026

Two Schoolgirls Friendship Is Tested In A British Dramedy With ‘Mean Girls’ Vibes [Sundance]

PARK CITY – Adolescent angst is evergreen. Somewhere in the world, a teenager is trying to grow into their body, learn how to appear less awkward in social situations, and find themselves as the hormones swirl. And often they have…

Jan 28, 2026