Dennis Cooper and Zac Farley on âRoom Temperatureâ

Jan 17, 2026

Room Temperature

Making an appearance on DC’s, the blog of author Dennis Cooper, each October are haunted houses and their amateur offspring, “home haunts,” the Halloween home makeovers that with varying degrees of imagination turn suburban dwellings into highly personal expressions of horror . For Cooper, the acclaimed author of works such as Closer, Frisk, God, Jr., The Marble Swarm and The Sluts, these necessarily ephemeral stagings are a particular kind of outsider art, which makes their cataloguing each year on Cooper’s website a work of invaluable archiving; they are installations in dialogue with American horror movie iconography in which such figures as Leatherface and Jason as well as more anonymous terrifiers are newly scary due to their placement within everyday neighborhoods as opposed to studio theme parks or multiplex movie screens.

As directors Cooper and Zac Farley note below about their Room Temperature, while there are plenty of horror movies set in amusement parks and in movie theaters, there has never been one set in a home haunt. (Shout out here, however, to the artist Cameron Jamie, whose 2003 Spook House captures one long night in such a homemade Detroit fright den.) But don’t mistake Room Temperature for standard-issue lo-fi indie horror. For one, the film’s measured editing rhythms make the concept of a “jump scale” completely implausible. More relevantly, though, Cooper and Farley pursue in Room Temperature — which is about a family staging a home haunt in their California desert home — latent, hazy traumas embedded within familial structures. For the film’s obsessive father, the annual home haunt is a kind of enduring ritual, one that his kids, who include the live-in French teenager Extra, become alienated by as they grow older. A local janitor, Paul, becomes a new member of the crew, drawn in by the mysterious menace of the redesigned home but only slowly clocking the anxieties and obsessions lying underneath the father’s artistic endeavor.

Room Temperature is Cooper and Farley’s third feature film. The California-born Cooper has been living in Paris now for decades, and he began directing with Farley, a French artist who studied at CalArts, on the 2015 feature Like Cattle Towards Glow, which was followed by 2018’s Permanent Green Light. As we discuss below, the new film is their first in English and first shot in the United States, but with its unpredictable segueing between dark humor and repressed dread, it resists in financing structure, crew, casting and overall affect the conventions of much American independent cinema. As John Waters wrote in Vulture when listing it as one of 2025’s best films, Room Temperature is “a purposely tedious and tender poetic head-scratcher of a film focusing on a family setting up their neighborhood home for a Halloween horror house. Just when you begin hating this film, you’ll suddenly realize—huh? I love it. It’s weird, creepy, and maybe … just maybe, great.”

After screenings this year at LA Festival of Movies, New/Next and at New York’s Roxy Cinema, Room Temperature will next play on January 28 at Seattle’s Grand Illusion cinema.

Filmmaker: In films when characters are making some sort of art work, there can be a temptation for the film’s production design to make something that feels very professional. In other words, what we see on screen is something that the film’s characters could never have created in real life. That’s not the case with Room Temperature, but was there ever that temptation? To lean into so-called “movie magic” when depicting these characters’s home haunt?

Farley: Not at all, because one of things we like so much about home haunts is their actual amateurism. We’re much more excited by a prop that looks profoundly homemade, where you see the materials and the process of its making. We were lucky to work with an incredibly talented set designer, Kristin Dempsey, who very quickly understood what we were after, so it was a pleasure.

Cooper: Both of us are interested in and involved in some way with the art world, so it’s more coming out of that kind of aesthetic than indie film. We would never think about trying to make it look like a regular film or whatever.

Filmmaker: Dennis, I’ve been a long-time reader of the blog, and I know you’ve done “Haunted House” days more than once. What were the origins of that interest? I’m assuming it comes from your childhood in the suburbs of LA?

Cooper: I’ve been interested in them forever. When I was a kid, I made them in my parents’ basement. Back then they weren’t something everybody did — if you were out trick or treating, sometimes people would put on a little display or something — but now they’re actually kind of a phenomenon. Zac and I go to LA every Halloween, because this is the center of the home haunt, and we go to 30 or 40 of them. We study them, like, “Oh, that’s interesting, this variation. How clever.” We’re looking at the props going, “This is so cool,” and the teenagers around us are all screaming, and the people who run the things are like, “Can you please keep moving along?”

We just love this beautiful outsider art form. Once a year, a family or group of people living in a house become artists. They get to transform their usual house into some special exciting thing. They get to be really ingenious and try to figure out how to scare people, how to trick them. They’re so sincere, very ambitious and [the haunts are] almost always failures. And the failures are so beautiful because they don’t have the money. There’s just a household budget, basically, and it’s just them and their kids. As far as I know, there’s never been a fiction film about a home haunt, so we thought that we should do this.

Filmmaker: Do you go to the ones that are more hardcore horror, where you have to sign waivers and there’s almost like a sadomasochistic element to them?

Cooper: Yeah, we have. Haunted Hoochie is a famous one. And there’s one here [in Los Angeles] called The 17th Door. You have to sign a waiver. At one point you have to kneel down, and it looks like a car is coming right at you. They blindfold you and put you against the wall, and then you’re “executed” — they shoot actual stuff at you. And when you go further into the haunted house, you become the executioner, and you’re shooting people. It’s never really dangerous, but it is a little unnerving. At the end, they put you into this coffin, and you’re like, “Oh, shit!” And the coffin raises in the air and tilts back, and the bottom drops out and you fall 20 feet into these balls. It’s kind of nuts.

Filmmaker: Even though you are both California people —

Cooper: Actually, Zac’s French.

Farley: Yeah, I only lived in California for two years.

Filmmaker: Okay, but you are both somewhat outside of the American independent film world as well as being kind of outside the French film industry, the whole CNC-supported system. How do you think about yourselves in relation to filmmaking communities, whether those communities are professional, French, American or sort of outsider?

Farley: Dennis and I have approached all of our films and projects in a very project-oriented way. Dennis mostly writes the scripts, and we work on them for a long time before we even begin to imagine how we are going to make them. The previous one, Permanent Green Light, we did in France, and we have this producer there, Nicolas Brevièr, who is very supportive and helped us navigate some of the public funding — not at the national level but more on the regional level. But, for this one, it was a completely new thing because we wanted to make it in the US and in English. And that disqualifies us from French public funding, so we had to go from scratch. It took a very long time to find the money. We didn’t want to do it in way that would give up any creative control. But, I mean, we don’t feel outside of film. We’re friends with filmmakers, we just don’t go about making films in a kind of “This is how you do it, and in this order” [way] because neither of us is fully knowledgeable about that stuff. We’re still kind of figuring out how things are usually made.

Cooper: In France, there are grants, but there are also all these strict rules about making films. There are strict limits on how much you have to pay everybody, how long you get to shoot. For instance, on our last film, which was a feature, we had to raise money for a short and then shoot it [on a short-film schedule]. It was very difficult because you can’t shoot a feature film there for less than 1 million euros, and you’re never going to raise 1 million euros for one of our films. So it’s tricky. There’s a reason why there isn’t an underground filmmaking scene [in France] because it isn’t set up to support that kind of work. That’s why we did it this way, which was just to go to people, mostly in the art world, and say, “Would you donate some money to us?” It took forever, but we eventually got there.

Farley: We’re both very curious people, and we talk to people. We’re not completely [unknowing of] how the world functions. But when we start working on a film, we set ourselves up to make every decision in a way that serves the project in the best way. I see people who are struggling to fit their projects into a pre-existing structure, and, in a lot of cases, that can harm the most exciting potential in the work. And so we make as much of an attempt as possible to find the right collaborators for the project but also the right approach to making them.

Cooper: And because we work with non-actors, we don’t go through SAG or anything. They’re all just interesting people, basically, so that kind of puts us on the outside. And then in terms of crew, for this film the DP and some of the central crew members were Russians who had escaped Russia and who were here and willing to work for us for much less than they were used to.

Filmmaker: Dennis, how do you approach the screenplay form in a way that’s distinct from your novels?

Cooper: Well, I mean, I don’t really read screenplays, so I don’t know, honestly. I might have read some Paul Schrader screenplays years ago. In fiction, every single fucking thing is in there, and then the readers take the material and make the thing in their head. With screenplays, you have to do a description of what you’re going to film, and there’s the dialogue, but you’re you’re basically writing hints. You don’t know who’s going to be in it, you don’t know where it’s going to be shot. The characters are just archetypes that are pretty open so that when you cast and find the right people, you can adjust it so the characters play into their strengths. It’s a kind of a recipe more than something that’s completely finished.

Filmmaker: Zac, how do you fold into Dennis’s writing process?

Farley: Well, I’m not a writer, and Dennis is one of my favorite writers. He does the heavy writing, but we talk about everything when he’s writing. We keep things very open until we go into pre-production, and that makes it so the thing continues to evolve until we’re shooting. We try to make it so that when we’re casting, scouting, working with production designers, that all those decisions can feed the project.

Cooper: Zac is much stronger at visualization than I am. I’ll write something that will seem really great to me, and Zac will say, “You know, this won’t look as interesting as you think it will. Maybe we can adjust it so I can do more with it filmically.”

Filmmaker: Are you both on set the whole time together?

Cooper: [Zac] is the director, and everybody’s answering to him, but we’ve discussed everything beforehand. On set, I’ll be like, “What about this?” Or, “Are you sure you want to do that?” But mostly I work with the actors to get the performances right.

Filmmaker: Tell me about moving your actors into the kind of performance zone you want them in, which is muted and the opposite of melodramatic.

Farley: This is our third film, and we’ve experimented in the first two films with a certain kind of presence on screen and a certain kind of relationship to the language of the film. But, starting from the casting, we really want to be permeable to their ideas and their selves. We want [the performers] to really participate in the film as full-on collaborators. The way we set up the filmmaking demands full focus and participation. All the takes play out very much at length. We’re not doing pickups here and there. So it’s very demanding on the actors, but we’re also very open to them bringing suggestions. For example, John Williams, who plays the father in the film — we did rehearsals two months ahead of time, and we knew how it was going to work, but he got on set and it was that times 17 or something. The first day and a half he was like, “Whoa, I don’t think I was prepared for the level of composition,” and we just adjusted everything to make it work, and now when we look at his performance, we’re like, how did this happen? It’s just extraordinary. So, it’s very exciting for us to set up these kind of constraints for everybody to be within a very specific register, for everyone to be in tune with everyone else, but also allowing for things we didn’t anticipate and for the performers’s desires to break through.

Cooper: By the time we finish the rehearsals, most of them know who the character is and can really do it. There weren’t any problems whatsoever [on Room Temperature], but because they are not actors, they don’t know what they look like [on screen]. So, if they have to be sad or angry, you might have to say, “It doesn’t read, so maybe change it a little bit so it reads like you’re feeling it on camera.” And then there’s all the timing, the spaces and everything, and we have them do that, but a lot of that is done in the editing.

Filmmaker: Are you writing parts for people who you know?

Cooper: The only person we wrote the part for was Stanya Kahn, who plays the mother, because we really wanted to work with her. We have a friend, Erin Cassidy, who’s a filmmaker, and she was the showrunner for the first two seasons of Big Brother. We gave her the types, and she reached out to people she knew, and then we just saw them. It wasn’t like a normal audition. It’s mostly you just sit down with them, talk to them for a while, do a little bit of line reading, and then it’s like, “That’s the father.”

Filmmaker: Tell me about the production design challenge of creating the haunted house. It’s always a challenge when you have a hero location that undergoes a big transformation. How did you organize the production around this change?

Farley: Originally, when we were first figuring out how to make this film, we met this group of cool and brilliant teenagers who had been doing home haunts for years, and we thought they’d be our set designers. It was a really nice idea, but they also do a lot of drugs and seem very disorganized, and that it might actually be difficult to organize them into this demanding and organized [production design]. Kristin, who is one of the production designers, is a real pro, and the sets were the main constraints on our scheduling because it was one location and actually a very small house. They built everything there at that house, and things had to built and unbuilt and rebuilt in some cases. The spreadsheets [showing the scheduling of the film] were mind boggling to me. Sometimes we would be shooting a scene in one room and [the art department] would be discretely painting the room next door.

Filmmaker: Dennis, do you think of the audience differently when you write a novel versus writing a script?

Cooper: No, it’s just technical. Does this work, does this read? What are the limitations? How is this going to be difficult for the viewer? How can we make it fun? How can we make a rhythm that’s challenging but then you get a little gift or something? But I never think of the actual viewer. I guess I probably think about myself [as viewer]. I’ve been writing fiction so long. I have a kind of sense of that world and how I fit into it. But the film thing, we’re trying to do something that’s really odd, you know? It feels like we’re trying to find people that we know exist out there, who are actually going to somehow like what we do. It feels very much like a frontier or something.

Filmmaker: What’s the next film? And will it be in the States or here?

Farley: We’re writing it now, but we haven’t gotten to the step of figuring out how to make it. I don’t know whether it will be in France or the States or somewhere else. Dennis writes in English, and we made it knowing it was going to be translated into French. So, as we were writing Permanent Green Light, we were cautious about making sure it would work in France. But we haven’t really done that with the script we’re working on now, so it’s a bit scary. But raising money for this film in the US was so difficult, and it took so long, not having access to grants and public funding. It’s not easy.

Cooper: If we could find in the States a producer who’d work with us, I’d like to shoot it in the States. I like the films to be in English. When you change [the dialogue] to French, you lose these little idiomatic things I love to play with. Even with the subtitles of Room Temperature there’s things you can’t do. For instance, at the beginning of the film, there a woman who comes into the bathroom and asks the janitor, “Do you think the students look up to you or down on you?” And they don’t say that in France. Or there’s a point where they kill Extra, and they’re digging the grave, and the janitor says, “I get it.” And you can’t say that [in French]. You have to say, “I understand.” It just kills the mystery.

Filmmaker: So how then do you feel about your books in translation?

Cooper: No idea because I can’t read them.

Filmmaker: You must speak a little bit of French.

Cooper: Very, very little.

Farley: The French translations of Dennis’s work are actually really good. I think the only novel of his that’s just understandably very difficult is The Marble Swarm. Just because it’s a kind of faux French-inflected [version of] English put back into French. They were forced to make decisions about how to do that in order to make the novel function in some way, so it works very differently.

Cooper: I have arguably the best publisher in France, and they care a lot and work very, very hard on the translations. I’m lucky to be published by them.

Filmmaking: Has making these films made you think about adapting any of your own novels?

Cooper: I don’t want to do that. They’re meant to work as texts, and I wrote them that way. There was a point when this novel of mine, God, Jr. was optioned for a while by Laika. I loved the idea of doing something animated, and they wanted this to be their first film that was live action and animation. They could never figure out how to do it, though. But, otherwise, no I don’t want to adapt [one of my books]. It’s more interesting to write something original

Filmmaker: Do other people to come to you for adaptations?

Cooper: The weird one is The Sluts, my famous novel, which is bewildering to me because it’s not my favorite. When people come up and say, “I like your work,” they always say The Sluts.

Filmmaker: Why do you think that’s the one that inspires so much interest?

Cooper: Because of the internet? I don’t know. It’s got a kind of mystery structure that I use like an actual narrative with, you know, tension and mystery. I never do that. I think it’s the sex. It’s just accidentally zeitgeist-y. But people have come up to me a number of times and say they want to adapt it, but none of them want to use the internet, which is the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. It takes place on the internet. Go find a book that has a bunch of stress hustlers and make a movie, but don’t take The Sluts off the internet. That’s crazy.

Publisher: Source link

The Housemaid Review | Flickreel

On the heels of four Melissa McCarthy comedies, director Paul Feig tried something different with A Simple Favor. The film was witty, stylish, campy, twisted, and an all-around fun time from start to finish. It almost felt like a satire…

Jan 30, 2026

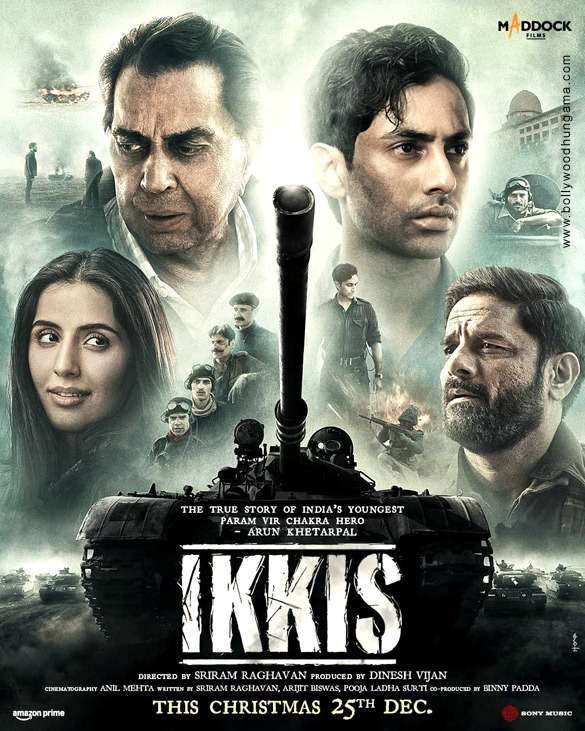

The Legacy Of A War Hero Destroyed By Nepotistic Bollywood In “Ikkis”

I have seen many anti-Pakistani war and spy films being made by Bollywood. However, a recent theatrical release by the name “Ikkis”, translated as “21”, shocked me. I was not expecting a sudden psychological shift in the Indian film industry…

Jan 30, 2026

Olivia Colman’s Absurdly Hilarious and Achingly Romantic Fable Teaches Us How To Love

Sometimes love comes from the most unexpected places. Some people meet their mate through dating apps which have gamified romance. Some people through sex parties. Back in the old days, you'd meet someone at the bar. Or, even further back,…

Jan 28, 2026

Two Schoolgirls Friendship Is Tested In A British Dramedy With ‘Mean Girls’ Vibes [Sundance]

PARK CITY – Adolescent angst is evergreen. Somewhere in the world, a teenager is trying to grow into their body, learn how to appear less awkward in social situations, and find themselves as the hormones swirl. And often they have…

Jan 28, 2026