âThe Underbelly of Lagosâ: Olive Nwosu on Lady

Feb 22, 2026

Lady

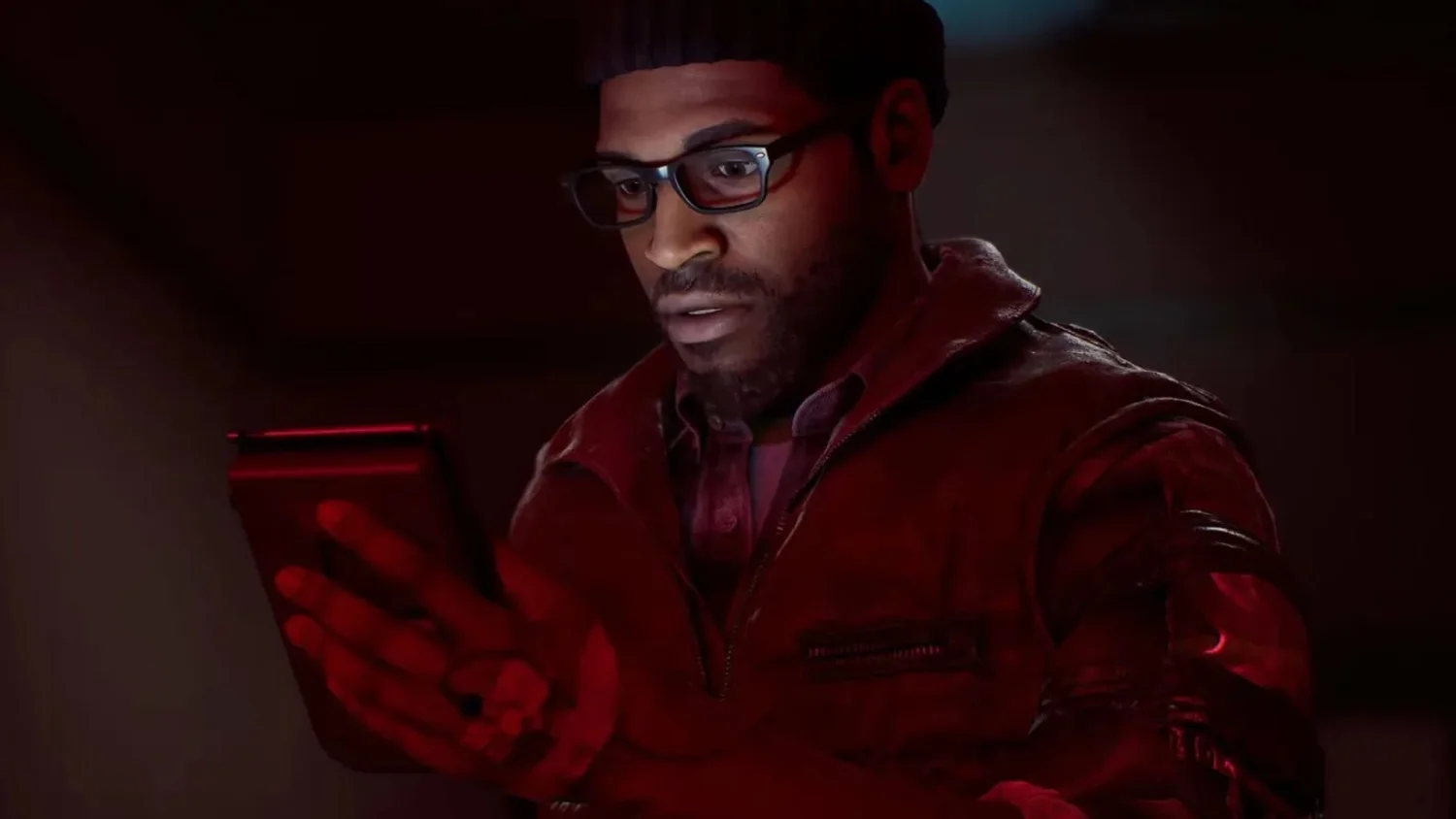

Lady, the titular lead of Olive Nwosu’s neo-noir feature debut about a taxi driver’s gradual solidarity with a group of Lagosian sex workers, possesses a piercing gaze. She’s not scanning you as much as she is preemptively fending you off. In her red taxi she stalks the nocturnal streets of the largest city in Nigeria, very much her own person, the only lady cab driver in a city on the verge of revolution around eradicating gasoline subsidies. Played with fiery commitment by Jessica Gabriel’s Ujah, Lady doesn’t even necessarily care that she’s a “woman in a man’s world,” or if she lives up to any cultural norms of femininity. Those expectations are too facile. Lady has a past she carries with her like armor even as she cares for an older female neighbor or affectionately pays extra to a little girl street vendor. No one else better get in her path. But one day, Pinky, a friend from her heavy past, shows up at her doorstep, asking for a favor. Lady’s nights are about to get a lot more charged, a lot more sexed, and of course, dangerous.

“Colorful” and “vibrant” are overused cinematic and festival descriptors of metropolises in the Global South and Sub-Saharan Africa. Portraying metropolises authentically is something Nwosu feels strongly about. Lady premiered at Sundance where it won the World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury Award for Acting Ensemble. While Nwosu admits she did write, at least in part, for festival audiences, she insists on guarding her insider perspective. She may have studied at Columbia University and currently resides in Britain, but she was born and raised in Nigeria. As such, Lady should speak to people in Lagos, too—especially the sex workers, among whom she conducted her research.

I spoke to Nwosu a few days before the film’s European premiere at the 76th Berlinale. She told me about the influence of Jane Campion, how the O.G. Taxi Driver served as a reference and her contrast with another well-known British-African female filmmaker. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Filmmaker: Since Lady premiered at Sundance and is now getting its international premiere in Berlin, I had a question about this idea of the film festival circuit and international films. When you were thinking about and writing this film, did you have a goal to screen it for a festival audience? And if you did, did you have a particular idea of how you wanted Lagos or urban West Africa to be represented?

Nwosu: I did. My first film Troublemaker played at Clermont Ferrand in France, and then my second short Egúngún played at TIFF and Sundance. So I’d done the festival circuit. And something I had noticed in watching films [that deal with] African history is the way that the continent has been shot. There’s often this kind of pastoral ideal and rural characters and settings. I was intrigued by that history, a lot of it coming from Francophone Africa in terms of the African festival circuit. So with Lady, I wanted to do something that really subverted that, that spoke about a contemporary city, a modern city, that was unafraid to lean into genre elements, that felt like a strong representation of what Nollywood also has to offer, that a local audience would also enjoy [in addition to the one on the] festival circuit. That was kind of the conceptualization of the film.

Filmmaker: Growing up in India surrounded by Bollywood, which is the Hindi-language cinema around Mumbai, I realized later that India’s independent films have nothing to do with Bollywood because, first of all, independent films come from all regions of India. I was wondering whether you too are irked by similar comparisons. If people talk about Nigerian cinema, do they automatically talk about Nollywood? If so, is that something that bothers you or is Nollywood influence something you actively work to bring into your films?

Nwosu: I think it used to bother me, to be honest, and these days it doesn’t. I have a real appreciation now for Nollywood. It’s such an enterprising industry, self-started and is imperfect, certainly. It could do with more development time and more financing. But again, it’s local people who are using the resources they have to tell local stories. I really appreciate that. There’s also independent film. My hope is that it’s not so separate where independent film becomes foreign-facing only and Nollywood is serving a local market. I feel like you can have a rich independent ecosystem that’s also speaking locally. That’s what I’m hoping Lady can be. It’s not afraid to deal with complexity. It’s not afraid to look at darkness, but it’s in conversation with local authenticity. Not to say that others aren’t, but the language is accessible.

Filmmaker: What other films from the Sub-Saharan African region or West Africa do you see this film in conversation with? The one that comes to mind is On Becoming a Guinea Fowl.

Nwosu: It’s not something I’ve consciously thought about, to be honest. I love Rungano’s work. It’s beautiful. And she’s one of few British-African filmmakers. So in that sense, I’m a conversant with her work. I feel that there’s a slight difference in that I was born in Nigeria and was in Nigeria the first 17 years of my life. So I think Rungano has this amazing lens of observation that’s slightly from the outside. In Guinea Fowl, for example, there’s an amazement at local culture. Whereas with Lady, I hope that we’re sitting inside the city and inside Lady’s character, and viewing Lagos through that point of view. So in that sense, I think there is a separation between the two films. A very different film is [Wanuri Kahiu’s] Rafiki. That felt like there was a vibrance and understanding of local culture that was exciting, even though it was looking at people on the margins.

Filmmaker: You were in the Sundance Feature Film Lab with Lady. What was the biggest story change that is now reflected in the film?

Nwosu: I loved being at the Lab. I had amazing mentors. I met Jane Campion there and she has been an amazing champion of the film and really encouraged me to lean into the interiority of Lady. The second big part of the Lab that I really took away from was the emphasis on research. The Lab was in two parts. After the first part, I went back home and spent two months with sex workers in Lagos, interviewing them, hanging out with them and writing a new version of the script. That really just deepened the architecture of the world. The rhythms of the group of women really comes from that experience, their camaraderie, their emotional vividness. That beautiful mix of freedom and darkness—the complexity—was real. These are women who are making economic choices, who are shamed in Nigeria but also have this freedom because they’ve done the most taboo thing and they’re actually often in systems that are less oppressive than the family structures they came from. There was something in that dichotomy and in that sense of agency that I really loved. That came from the research process after the Lab.

Filmmaker: About the research process, how do you go about doing it?

Nwosu: I was lucky I had a local fixer who was already kind of integrated into the community. I think especially for communities like that, finding someone local who they trust as a way in is important. Specifically with sex workers, there’s a lot of fear around police. So building that trust is the biggest part of it. I found that not many people had ever asked the women questions. There were just lots of assumptions. So once they felt comfortable, they very quickly started to open up. They were hungry to share their stories. For me specifically, because I have a background in psychology, having a trauma-informed process is helpful. Thinking through how you create emotional safety for the people that you’re interviewing. Then a lot of observation. You just start to see details of how people behave that you can work with.

Filmmaker: What is one concrete thing that a filmmaker can do to create emotional safety for vulnerable subjects?

Nwosu: I would say really listening to them. I feel like filmmakers often talk a lot. [Laughs.] We have a lot of ideas. It’s enough to ask one question and then see how organically a person takes it. Often with the group, I would have maybe four questions and then just allow each one to build. I would also say to really think about how you create a space where people feel comfortable. Throughout the process we had an intimacy coordinator. We had a psychologist on set. When the actors know that they have these support systems, just that knowledge is plenty, especially in Nigeria where often that doesn’t happen. The last part of it was educating the crew. Having a lot of workshops in advance around being respectful to the women, around how we speak with one another, making sure everyone is speaking the same language.

Filmmaker: I’m curious about the specificity of working with an intimacy coordinator in Lagos and in terms of the Nigerian industrial context?

Nwosu: Honestly, it was wonderful. We worked with an intimacy coordinator who is South African, Sara Blecher, but she’s basically built out the intimacy program in much of Africa. We looked but we didn’t find a fully-trained intimacy coordinator in Nigeria, but who we did find was a woman, Yeside Olayinka-Agbola, who runs a women’s sexual empowerment group. So we paired someone who had the technical know-how with someone who had the cultural sensitivity. Together they created a framework that I think the women really responded to.

This kind of stuff is the most exciting part about making films in Nigeria for me. It’s how you start to build new systems and figure out the puzzle of who works with who, combining that technical skill with the specific culture that we’re working in. What did that look like for Lady? I would say, even thinking about how there’s so much touch in Nigerian culture—people hug, people hold hands—butthen there’s the difference between doing that with and without consent. These are the kinds of conversations that we have to begin with, before going into design of the scenes that need intimacy coordination.

Filmmaker: Do filmmakers use intimacy coordinators for scenes outside the sex scenes?

Nwosu: It’s primarily the sex scenes but honestly just intimacy in general. It’s kind of like sculpting intimacy throughout the film, because Lady is such a guarded character and she has this backstory. So we were thinking about how she responds to touch. Sometimes that’s overt, like when she’s seeing sex in the mansion, but it’s also just slight moments between her and the women.

Filmmaker: One of the most powerful moments in the film was when Lady is in the cab and she shouts, “Don’t touch me!” How did you approach working with everyone to make sure you got that moment?

Nwosu: Yeah, I really loved that moment. I think it speaks to the character’s complex relationship with physicality. It started with Jess crafting Lady’s discomfort with her sexuality, down to her clothes and this armor she’s putting on to hide from the world. Then we were really thinking about how she would respond after such exposure at the sex party. We had to shoot [the sex party] scene very quickly, to be honest. We were running out of time. We only got two or three takes, and it’s a long push in, so it takes a lot of set-up.

But I have to say that Jess and Amanda, who plays Pinky, were very connected from the very beginning. So really it was about letting them sit in the moment, prepping everything in advance so that they could really take their time and perform.

Filmmaker: One of the things that really stood out for me is how much night photography there is, both interior and exterior. Could you talk about working with your cinematographer Alana Mejia Gonzalez?

Nwosu: Most of the shoot was nighttime. I think it was four weeks of night shoots. I mean, we always wanted to contrast Lagos daytime and Lagos nighttime. It’s about the underbelly of Lagos and what happens when the city goes dark. So for me, from the very beginning, that was obvious. Taxi Driver was always a reference. That film also lives so much in the nighttime.

I would say working with Alana, we talked a lot about a new noir look to the film at nighttime contrasting with a more verité style during daytime. That’s where a lot of the lighting ideas started from, like leaning into high contrast, leaning into real darkness, leaning into the colors of the nighttime world. Lagos in the daytime is so busy and hot, and then at night it gets cooler and quiet.

Filmmaker: You spoke about high contrast versus real darkness. Was there a particular shot or scene where you were actually not sure what choice you wanted?

Nwosu: Once we settled on the noir look, it became pretty clear [that we would be] leaning into the inkiness, the mystery and the shadows of Lagos. Our lighting budget was very high. [Laughs.]

Filmmaker: What choices did you have to make in color grading?

Nwosu: We made the film darker in the grade. That was a risky choice, but I really love the deep blue that we landed on. I think for dark skin, it sits really beautifully, like the chroma and the highlights. That was something that came from my grader, Gareth Bishop. Just going so dark that sometimes all you can see are the outlines of the characters’ faces.

Filmmaker: Somewhere in the middle of the film, there’s this impressive long tracking shot on the streets, in the day, when people are reacting to the news of the removal of the petrol subsidies. What was the process of getting location permits and then pulling off that tracking shot?

Nwosu: Yeah, that shot was so hard. [Laughs.] I think our crew had to start laying tracks around 4am, because past mid-day the shadows would fall on the wrong side, and then you could see the camera. So we had a very limited amount of time. But I knew I wanted to do that as a long take just to fully capture the madness of Lagos but also petrol stations and the fuel crisis. It’s almost a mini portrait of the city in that one shot.

Permits are semi-official. [Laughs.] We were able to get permission to shoot in a gated community with like 300 homes, and there is a petrol station in it. We had to close down half the street. Eventually, I think we annoyed the community so much that they told us to leave. But again, we had done prep because we knew we only had so much time. So it was about knowing exactly what we wanted to do with that time.

Publisher: Source link

Pastiche Horror Wears Its Aesthetic Influence On Its Padded 1970s Shoulders To Both Juicy and Exhausting Effect

There's a common refrain about marriage that stipulates you'll end up finding yourself in a myriad of new relationships throughout its lifespan. The person you marry is not the person they will be in twenty years. Hell, they're not the…

Feb 21, 2026

Sam Raimi’s Bonkers Survival Horror Comedy Is Deliriously Demented

There are practically three movies inside genre maestro Sam Raimi’s hilariously bonkers “Send Help,” a deviously dark thriller-cum-horror comedy. There’s its first act—office politics and workplace f*ckery, hinting at power-play dynamics and control-freak dominion. Then comes its second chapter, where…

Feb 21, 2026

Try Not to Cry During HBO’s Most Emotional Goodbye Yet

Editor's note: The below recap contains spoilers for The Pitt Season 2 Episode 6. A third of The Pitt Season 2 is already over. In that time, audiences have watched Dr. Michael "Robby" Robinavitch (Noah Wyle) struggle through his last…

Feb 19, 2026

Ryan Murphy’s JFK Jr. Drama Hits Hardest in the Scenes That Never Made Headlines

When The Crown premiered its final season, it felt like the end of an era. The Netflix series created by Peter Morgan dove deep into the British monarchy through the lens of Queen Elizabeth II and her immediate family, while…

Feb 19, 2026