âWhat Is a Golf Course but the Gentrification of Land?â: Rafael Manuel on Filipiñana

Jan 27, 2026

Filipiñana. Photo Credit: Potocol, Ossian International, Epicmedia, Easy Riders, Idle Eye

In Filipiñana, tension often lives inside the image itself: a desiccated pine tree creaks against a bright blue sky; mangos left to rot on the branch. There is beauty here, but also decay. Rafael Manuel’s debut feature expands on his 2020 Berlinale-winning short (which is streamable courtesy of The Criterion Channel) to offer an extended yet precise parable about class, memory, and quiet violence in his home country, the Philippines—filtered through the microcosm of a golf course on the outskirts of Manila during a scorching summer day.

The film follows Isabel (Jorrybell Agoto), a new tee girl, as she acclimates to her surroundings and moves through the club’s stratified spaces: dining rooms shared with other laborers, a patio where Chinese tourists eat neat slices of cake, and the greens she is forbidden to lie on. As Isabel circulates, the hierarchies, rituals, and unspoken rules governing the space slowly come into focus. Manuel shoots largely in static, deliberate compositions and long takes, often stitched together with precise match cuts that emphasize a sense of repetition and containment.

Having previously spoken with Manuel about his short, it was a pleasure to reconnect ahead of his feature’s premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, where Filipiñana plays in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition section. The film will also screen at the Berlinale and is executive produced by renowned Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke, Manuel’s mentor.

Filmmaker: I’ve never heard of tee girls like Isabel before. They’re literally sitting in front of the golfer at the driving range, inches away from being hit in the face. Is that a real thing? Where did you first encounter this?

Manuel: My parents are in the golf equipment business. Golf Depot in the film is actually my parents’ company, so I’ve been around golf ever since I was three or four-years old. I always found the idea of tee girls so absurd, especially the further I got away from the world and my parents, and the more I saw it from an outside point of view. They say to write about what you know, and I know this world.

Filmmaker: How did you think about scale when adapting this into a feature? More happens, but it’s still spare and restrained, maybe becoming your style.

Manuel: I don’t know about it being my style per se, but it’s the style that really matched the film. Because we talk a lot about inaction and action—themes that the film deals with that exist very much in a golf course— it just didn’t make sense to inject so much plot into this world. It was something that I already tried to play around with and experiment with in the short film. For the feature, we did introduce a bit more narrative—to respect the form—while still keeping the audience within this extended sense of time. I thought about it as a kind of coming-of-age story for Isabel, which worked for me because the film is really about collective memory. Her coming of age is a journey inward, into memory—remembering things from her past. In the same way, I feel that, as a people, Filipinos need to remember what came before so we don’t repeat the same mistakes.

Filmmaker: The film actually opens with city scenes in Manila that weren’t in the short. We see people lining up [to collect] water from tanks, images that recall earlier Philippine cinema. Was that about setting the economic context, especially for viewers who might not be familiar with those conditions?

Manuel: It was definitely context-setting but also very pointedly introducing images that people already know from the Philippines and connecting it to a side of the Philippines that they may not know, and saying that these are two [sides of the same coin]. It’s grounding the metaphor in images people are already familiar with and actually contextualizing the violence, which is the same kind that exists in both worlds.

Filmmaker: There’s an uneasy sense of humor that starts in those opening scenes, too. The tour guide tells a joke about the weather that made me laugh, but the patrons barely acknowledge it and it hangs in the air, unanswered.

Manuel: These hanging moments were definitely intentional as a way to encourage the audience to put themselves in those tourists’ shoes. Something similar actually happened at the premiere. The end credits start a bit earlier than people expect, but they’re not the real ending—there’s still an important moment afterward, with Isabel swimming out. Because of the 2:45PM time, as soon as the credits rolled, some people clapped, stood up, and left for the next screening. Some members of my team were sad about this because, obviously, a really beautiful moment is coming up, after Isabel calls out for help and the golfers walk away. Then, two minutes later—as Isabelle’s swimming out—you have people in the audience who think that because the movie appears to be over, they can walk away too. That to me was crazy.

Filmmaker: You’re “stretching” time in [the vein of] durational cinema and reshaping how the audience is asked to sit with these moments.

Manuel: For me, the film is really about taking themes that Filipino cinema has been wrestling with for a long time and finding a way to make them more relatable for a Western audience. That moment was like a mirror to me—art imitating life, and life imitating art at the same time.

Filmmaker: Clara seems like a foil to young people today who come to study in the States. She’s visiting her home country and she seems uneasy, clocking the social differences, but ultimately remains compliant. What role did she play for you? Is there hope for a character like her?

Manuel: I can’t speak for all Asians, but for many Filipinos who move abroad—as I did—there’s a deep sense of guilt tied to pursuing your dreams while knowing what’s happening back home. With Clara, that feeling is very present. In a way, her arc is the inverse of Isabel’s. Isabel is coming of age; Clara is a tragic figure. She begins from a principled position and is skeptical, but she doesn’t move beyond that. Formally, I tried to reflect this contrast too. The first image of Isabel shows her waking up, opening her eyes. The last image of Clara is her closing hers. They mirror each other, but they also mark opposite trajectories.

Filmmaking: That violence at the end of the film is also different from the short. How did you get there?

Manuel: I wrote a treatment for the feature before I shot the short. Then I realized it really needs to be an evolution, not just an expansion. It’s easy to lay the blame on one side when they’re not represented, and I really didn’t want this to be a film that lays the blame on any one side. We all have our part to play in perpetuating a system that doesn’t really work, and that’s when we got the idea of the character of Clara. In the short, I explored the milieu through one point of view. Like Isabelle, Clara is an outsider to the golf course.

But because of her social status, she has more access than Isabelle and Isla, the little girl who dies at the end of the film. I always knew that if I wanted the theme of invisible violence to stick in the end, it would need to land in a very real way that connects both characters in both worlds. I was very influenced by the ending of Lucretia Martel’s La Cienega, which deals a lot with this generational and structural violence. In the end, a kid falls from a ladder, but you don’t really see it.

Filmmaker: Lucretia Martel also uses sound a lot in her movies. How did you think about sound as a mechanism of power within the film?

Manuel: I think mainly in sounds. If you see the script, you’ll see that I really write down the sounds. Half the time, I’m thinking about how I would spell out what the sprinkler sounds like. Is that a CH or is that an SCHK? The most obvious example is the sound of the golf club hitting the ball. We didn’t add anything new; we just raised the existing sound by maybe three decibels. That tiny shift already brings out the violence of the sport. Sound also becomes a way of expressing heat and drought, which are forms of violence in my country in themselves. That’s why there’s so much inaction in the country—because of this fever or heat-induced fog. Another example is bringing up the cicadas and other essentially wild sounds of the land that existed before it was gentrified into a golf course; you’re calling back to what the land once was. And in doing so, you create this link between memory, sensation, and emotion.

Filmmaker: So you didn’t have to manufacture too many sounds or Foley anything?

Manuel: No, not hardly any. It’s a lot of recorded sound.

Filmmaker: There’s a section where the sounds of the staff’s chores—sweeping, stacking chairs, cleaning the pool—are cut together with diegetic music, almost like a choreographed sequence. It’s like they’re whistling while they work.

Manuel: I love that example of whistling while you work because the Filipino people work very hard. They have to. Many of the people who work in the service industry live hand to mouth. Usually you’ll find that we’re also very musical people. The harder the work, the harder the life, the more musical the person is, and the more they sing because it’s like an escape in itself. I don’t know if it has its roots in Catholicism, but I’m relating that to the sequences of musical montage, that’s really where it’s rooted in the beauty of finding an escape amidst a hard life.

Filmmaker: The film’s color palette is deceptively gentle—pastel, controlled, almost decorative—despite the violence embedded in the world of the country club. How did you approach color as a thematic and narrative tool? I remember from when we last talked, you spoke of inherent violence, and the gentrification of violence, and how you wanted to use the tools of cinema to showcase that through texture, color sound.

Manuel: I wish I had my cinematographer here because it was very much a collaborative effort between directing, [Xenia Patricia’s] cinematography, and [Tatjana Fanny Honegger’s] production design. What is a golf course but the gentrification of land? Oftentimes they try to hide violence by making something look pretty, very manicured. That was the design philosophy we had. We pulled a lot from the ‘60s and the ‘70s with this idea of retrofuturism or a nostalgia for the future, which is contradictory. Pulling colors, design. and fashion from that era, we tried to play around with a period setting that felt timeless. It’s very important that when you watch Filipiñana, it’s hard to tell if it’s happening now, 50 years ago, or 50 years in the future. That calls back to themes of colonialism—for me, post-colonialism doesn’t really mean anything because we’re still living in it in the Philippines.

Filmmaker: Do the golf course employees, like the tee girls and caddies, have those distinct outfits?

Manuel: It really depends on the golf course. They do have these uniforms but we just made them a bit more aesthetic.

Filmmaker: Did you shoot on film?

Manuel: Both in the short and the feature, we’ve always toyed with it, but we could never afford it. But we are very lucky to work with Toby Tompkins of Cheat, based in the U.K. He’s one of the world’s leading color specialists in film simulation. He does a lot of color studies related to film, and we worked with him along with Vlad Barin, his protege. They just got bought out by Harbor [Picture Company]. Working in post color, we added a lot of heat to the film, with flares and other elements to create the film’s atmosphere.

Filmmaker: You also filmed in 4:3 which is not the most obvious choice for something set on a golf course.

Manuel: Golf courses are vast expanses of lush greenery, so it would make more sense to shoot maybe anamorphic or something—but by taking out the width, you gain verticality. We tried to emphasize power relations through the verticality of the frame and framing within frames. For example, the shot that, for me, was the genesis of the entire idea of the film is Isabelle between Dr. Pallanka’s legs. So much of the power relation that the film is about is in that. One thing that’s not present in the short that we’ve developed in the feature is these very slow zoom-ins. Our evocative, poetic camera movement allowed us to talk about or symbolize memory.

Filmmaker: The last scene is shot from a far distance. Why did you choose that? To me, it seems connected to what you were saying about inaction—it positions the viewer as a passive observer. The violence is far off in the distance and you might not even notice it.

Manuel: That’s spot on. I think getting too close at that moment is a disrespect to the audience. You’re telling them how to feel—when the entire situation in itself already says a lot.

Filmmaker: The flip side is that some viewers might disengage—like at the premiere when people left as soon as the credits rolled.

Manuel: The people who do stay—they’re really paying attention. Instead of an ending that people see and forget, those who stayed—and there were a lot who did—know that others are missing something. There’s a kind of power in that. The moment will live on longer.

Publisher: Source link

The Housemaid Review | Flickreel

On the heels of four Melissa McCarthy comedies, director Paul Feig tried something different with A Simple Favor. The film was witty, stylish, campy, twisted, and an all-around fun time from start to finish. It almost felt like a satire…

Jan 30, 2026

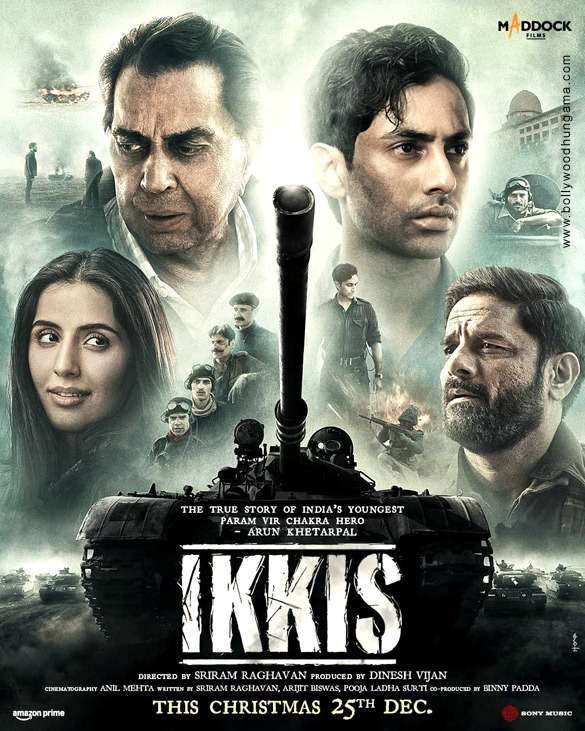

The Legacy Of A War Hero Destroyed By Nepotistic Bollywood In “Ikkis”

I have seen many anti-Pakistani war and spy films being made by Bollywood. However, a recent theatrical release by the name “Ikkis”, translated as “21”, shocked me. I was not expecting a sudden psychological shift in the Indian film industry…

Jan 30, 2026

Olivia Colman’s Absurdly Hilarious and Achingly Romantic Fable Teaches Us How To Love

Sometimes love comes from the most unexpected places. Some people meet their mate through dating apps which have gamified romance. Some people through sex parties. Back in the old days, you'd meet someone at the bar. Or, even further back,…

Jan 28, 2026

Two Schoolgirls Friendship Is Tested In A British Dramedy With ‘Mean Girls’ Vibes [Sundance]

PARK CITY – Adolescent angst is evergreen. Somewhere in the world, a teenager is trying to grow into their body, learn how to appear less awkward in social situations, and find themselves as the hormones swirl. And often they have…

Jan 28, 2026