Charlie Polinger on The PlagueFilmmaker Magazine

Jan 31, 2026

The Plague

The awkwardness of puberty is exacerbated by a cruel social game in The Plague, the feature debut from writer-director Charlie Polinger. Set in 2003, Ben (Everett Blunck), a shy yet precocious kid, finds himself shipped off to a water polo camp very far from his childhood home in Boston. His young teammates can practically smell Ben’s desperation for belonging; luckily for him, there’s already someone cemented at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Eli’s (Kenny Rasmussen) reputation as a maladroit athlete and for inept conversationalist make him an easy enough target for bullies, but the kids have added an additional element of psychological warfare to the mix.

After spotting that Eli’s rash guard conceals a red, flaky skin disorder, the boys have concluded that he has the titular plague, a contagious disease that affects social standing as much as it does dermatological well-being. If anyone ever touches him, they must thoroughly wash themselves before they’re considered full-blown infected. Even something as innocent as Eli sitting at the same lunch table sends his teammates running and screaming. Ben toggles between joining in on the bullying and sympathizing with Eli, who he discovers shares similar interests that some of the other boys might deem “nerdy.” One day, when Ben finds it in his heart to treat Eli with extreme kindness, he is subsequently ostracized by the group. Even more odd, Ben begins to itch and scratch his skin, the result of a rash that has mysteriously manifested. Could the plague actually be more than just an adolescent hazing ritual?

Still a few years ahead of the advent of iPhones and social media, The Plague analyzes this coming of age dynamic in a refreshingly analog incubator. Yet there’s a lot that’s timelessly familiar about this intense era of self-discovery: the boys exchange raunchy stories, discover new music (Moby’s “Feeling So Real” factors quite heavily) and sneak out to chug beers, smoke weed and set garbage on fire. Any inclination toward simple nostalgia is totally rebuffed by the anxious atmosphere conceived by Polinger, whose attention toward eerie sound design, gnarly prosthetics and frantic choreography (in and out of the water) conjures unrelenting dread.

The Plague released in New York and Los Angeles theaters on Christmas Eve and now expands wide via Independent Film Company. I spoke with Polinger via Zoom shortly before his film’s theatrical release, our conversation spanning his own repressed summer camp memories, the Lynchian atmosphere of indoor pools and the iconic Darude song that nearly made its way into the film.

Filmmaker: The inspiration for this film came from personal diaries you rediscovered while at home during COVID. How much of this summer camp experience have you carried with you and what reemerged after rereading your own account?

Polinger: It was almost entirely rediscovered. I hadn’t thought about camp during this time in my life very much. I mean, I went to another camp after the sports camp that was more of a theater camp. I had a great time there and became lifelong friends with some people. But I had kind of repressed my less good camp experiences. Reading some journals I kept just brought back this flood of memories and that inspired me to explore that time not just in my life, but in anyone’s life.

Filmmaker: Did any of these experiences tangibly make their way into the story? Or did they mostly just serve as a jumping off point?

Polinger: It was definitely more of a jumping off point. I wouldn’t say it’s an autobiographical movie, but the idea of the plague as a game was a real thing that I had experienced. Some of the characters in the movie were definitely inspired by certain people that I knew, but I’d say by the time I finished the screenplay, it became a total work of fiction.

Filmmaker: What felt imperative about setting the story in 2003? Obviously, you’re filtering the story through your own coming of age, but I’m curious what you felt wouldn’t translate to 2025.

Polinger: I was excited about exploring a certain age through the lens that I saw it through at that time, because leaning into the memories just made it feel as personal as possible. I also think that the version set today is a different type of movie. This type of bullying or these types of group dynamics definitely still exist, but social media would play a big part in it. Even the sense of humor would be more specific to that. It’s a different world and different tools are used for some of the same behaviors. The thing that I’m more of an expert in is growing up in that particular era.

Filmmaker: Speaking of the period specifics, there are boomboxes and payphones and certainly not a cell phone in sight among the boys. Did your young actors abstain from using their own devices during filming, or was that too tall of an order?

Polinger: We tried to have a “no phone” rule when we were on set anywhere near the camera. We even tried our best to not have any of the crew have our phones out either, just so it could be this sort of sacred space and let it feel real to the time period. But we didn’t always fully succeed at that [laughs].

Filmmaker: How did you prep your young actors for embodying a kid from 2003?

Polinger: I gave them hang out movies from the time or set during the time to watch. I gave them booklets of CDs with a CD player and suddenly they were singing Eminem lyrics [laughs]. They just started organically digesting the culture. We’d put a Game Boy on a bed and let them figure it out. It was a little more real than me trying to talk them through it.

Filmmaker: Some of the cast are somewhat established actors in their own right, with lead Everett Blunk previously starring in last year’s Griffin in Summer, and his friend, played by Elliott Heffernan, was the lead in Steve McQueen’s Blitz. I know you cast some of the other actors via social media, but I’m curious how you guided experienced and non-professional child actors in order to create this really intense social hierarchy?

Polinger: You didn’t really feel that some of these actors have been in movies before and for some it was their first time. Everyone came so prepared and took it so seriously that it felt like everyone was just here to work. It was really more about building the dynamic with the group in general, getting everyone in a room, giving them time to hang out, play games and read the script. Even teaching them water polo became this [bonding activity] where they could get lunch afterwards and complain about how difficult water polo is. They just naturally built the kind of relationships that you might have at a camp. I think it was more about getting everyone in sync rather than merging acting styles.

Filmmaker: By putting these boys in an environment that mirrored your own youth, did you start seeing any of the dynamics that you recounted in your diaries sprout up anew?

Polinger: Maybe because we cast a really nice group of boys, everyone got along and it was really fun. I do think some of the fun experiences that I had felt mirrored. Like when I first did a play or something. Coming together and hanging out felt reminiscent of that. I mean, we were in Romania and none of us really knew anyone there, so we were all hanging out and trying to find the best spots. We were eating burgers and exploring the city together. It felt like we were on this shared adventure.

Filmmaker: I’d like to know more about what conversations were had about some of the more mature themes of the film, like when the boys are sneaking out, setting shit on fire, rolling spliffs and drinking beer. How did your intimacy coordinator, or even the parents involved, navigate this realistic aspect of coming of age that is maybe a little uncomfortable to confront?

Polinger: I found that parents, or even just adults reading the script, were nervous about things that all the boys were incredibly aware of. If anything, they were eager to push further based on their experiences, which is sort of what I had expected. Getting them to break stuff and set things on fire was the easiest thing ever. Stopping them when we called “cut” was more of a challenge [laughs]. Even the more intense stuff are things that they’ve all experienced in their lives. They’ve experienced bullying, they’ve experienced talking about sex. It was pretty easy to have a conversation with them. In a way, I think adults feel more awkward about it than they do.

Filmmaker: During the process, did you feel this reinvigorated sense of, “I thought my experiences were so far removed from theirs, but it’s much more similar than I expected?”

Polinger: It was very easy to connect with them and the generation gap didn’t make it hard. It was like, “I know a kid who reminds me so much of Eli or a kid who reminds me of Jake.” I was able to hang out with them and build a relationship. Trying to fit into a group is something that people are always going to have to navigate.

Filmmaker: Joel Edgerton is great in a role that is intentionally slight; his lack of actual oversight and authority is a really dreadful element. How did he and the child actors establish this guise on and off screen? Did you keep him intentionally at a distance or was he really closely collaborating with them during the process?

Polinger: It was a mix. He was there for a certain chunk of the shoot. He would be there supervising the water polo stuff. There’d be [other] adults peppered throughout [these scenes], chaperoning the boys at the camp, but you’d sort of keep them in the background. Joel’s character as a coach really felt very connected to Ben’s experience. But Joel was definitely hanging out with [the boys] and he was on the sidelines actually coaching and learning how water polo worked. I think that [the boys] were able to build a similar dynamic with him that they would with a coach.

Filmmaker: Meanwhile, for the brief, almost mythical presence of the girl campers, I assume that you scouted fledgling synchronized swimmers?

Polinger: We found this awesome synchronized swimming team in Romania who wanted to be in the film. We saw their routines and they were incredible. It was very easy, we set up the shot and put the boys on one side and the girls on the other. We were just like, “Girls, you’re walking in and you just all dive into the pool. Boys, you are heading out and grabbing your bags and leaving.” That’s all we even said. All the interactions between them happened naturally just by having to pass each other. We filmed it in slow-mo and I didn’t even say anything the first take. Everything that happened felt very organic to what happens when you have what we called “the changing of the guards” with the swim teams. Everyone was able to stay in character, not look at the camera and just keep it real.

Filmmaker: Tell me about choreographing all of this movement with Celia Rowlson-Hall, whose work in The Testament of Ann Lee hit theaters at the same time as your film. I assume she shaped some pivotal dance sequences, but did she have any influence on the underwater aspects of the choreography?

Polinger: She most specifically focused on the dance that Eli does at the fire and that Ben does later. She worked with both of them to find something natural in their bodies but that also worked with the music. The synchronized swim routine was something that the girls already knew before the shoot.

Filmmaker: Did you have any guidance for her in terms of the choreography or did you allow her to let the boys play around and see what felt best?

Polinger: The first thing I sent her were different videos I could find of boys around that age who are on a sugar high flailing their limbs around. Something between dancing and an exorcism. The idea of a top spinning or gyrating was in the script, so we talked about that.

Filmmaker: How did the music that you ended up choosing influence the movement?

Polinger: I found the song by just listening to everything that I have. I have these old mixtapes that I kept. I was listening to all the music from that time period on these CDs I’d made myself, and that Moby song was on one. There’s something about it that is so chaotic, freaky and kind of liberating. It’s a lot of different emotions at once and it felt like a song that if you had enough Red Bull or something [and heard it] at thirteen, you could go crazy. We’re really lucky that Moby was willing to let us use the song for a pretty good price. When Celia heard the song she was also like, “I totally see how this clicks.” She told Kenny, who played Eli, “Listen to it all the time.” It became his favorite song. When it came on, he just automatically wanted to move.

Filmmaker: Were there any other songs in the sunning that you rediscovered?

Polinger: “Sandstorm.” Moby is a slight exception, but a lot of the Euro dance stuff of that time, like “Freed From Desire.” There’s another one I’m trying to remember now. “Castles in the Sky,” maybe. Any of those techno songs that were really big. But the Moby one was my favorite because there was something really pained about it while also being really upbeat, and that felt kind of special.

Filmmaker: There is definitely something that happens to your brain chemistry when you hear “Sandstorm” for the first time at thirteen.

Polinger: “Sandstorm” would be very fun. I mean, we were lucky to be able to get some Ying Yang Twins. Our music supervisors, Kayla [Monetta] and Alison [Moses], worked some serious magic getting “Around the World (La La La La La).” I never thought we would get some of those songs.

Filmmaker: How did the needledrops play into the overall sound design of the film, which is really intentional and intense?

Polinger: It was all about trying to immerse the audience in Ben’s psychological state and in his subjectivity. It was this constant anxiety about the social elements around him, like hearing voices, lockers slam, music playing. All of those things are indicators that you don’t know who is going to be around the corner. Is it just some random people or is it the people you don’t want to run into? We would use voices, routines and music to create stress for him. The constant dripping and the crazy sounds of these indoor pools and their machinery sounds like a David Lynch movie. I would take recordings on my phone and show them to Damian [Volpe], our sound designer, and we tried to build that out. You’re in this cocoon of bizarre noise, like you’re trapped in this place. The two times that he leaves, you really feel that sound fall off. It’s this relief, like, “Oh my God, we’re out of the prison.”

Filmmaker: Body horror films about puberty are plentiful, but I appreciate the squirminess of the realistic rashes and zits here.

Polinger: It’s the psychological horror of being a 13-year-old in the social dynamics and the body horror of being a 13-year-old. It was very literal in that way. By focusing on the details, it’s really squirmy because most people have dealt with this. I mean, I had really bad acne and was on Accutane. I remember sneaking into the bathroom to try and pop a pimple and you can’t actually get it to pop. It’s nasty. In some ways, that’s a lot more intense to look at than someone’s head exploding, because we’ve all been there. I could barely look at some of those scenes, even though I know that they’re just prosthetic pimples.

Filmmaker: And how did you work with your makeup designer to reflect what the titular plague looked like and what real life dermatological disorders it may mirror?

Polinger: It was actually a pretty thorough research process because we were looking at a few different things that can cause these types of rashes: chlorine, fungi, stress, when you don’t change your wet shirt. We got all these research photos and we did all these tests just trying to keep it in a place where there’s enough room for interpretation of what it could be, which is a lot more stressful for Ben. It’s “just a rash,” but it grows and it’s weird. We really thought through exactly how bad it was from scene to scene. It was very boarded out in terms of his own psychological journey and how bad the rash is actually getting.

Publisher: Source link

The Worst Episode Ever Proves It Needs To Course-Correct ASAP

Because my favorite 9-1-1 character is Eddie Diaz ( Ryan Guzman) and he's been getting sidelined all season, I had high hopes going into this week's episode. Season 9, Episode 10, "Handle with Care" sees the return of Abigail (Fallon…

Feb 1, 2026

Mother-Son Road Trip Movie Is Sweet but Overly Familiar

The road trip movie is one of the most beloved film genres of all time. From hilarious, irreverent comedies like We’re the Millers to heartwarming dramedies like Little Mrs. Sunshine, Oscar-winning dramas like Nomadland, to documentaries like Will & Harper,…

Feb 1, 2026

The Housemaid Review | Flickreel

On the heels of four Melissa McCarthy comedies, director Paul Feig tried something different with A Simple Favor. The film was witty, stylish, campy, twisted, and an all-around fun time from start to finish. It almost felt like a satire…

Jan 30, 2026

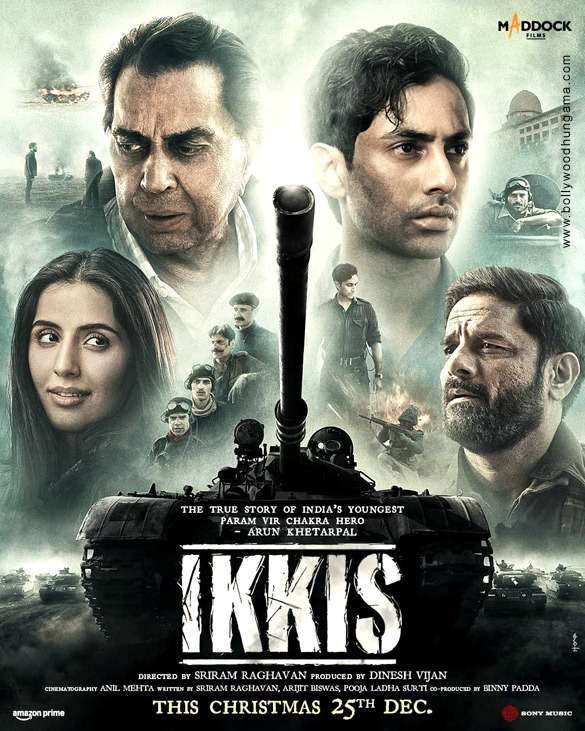

The Legacy Of A War Hero Destroyed By Nepotistic Bollywood In “Ikkis”

I have seen many anti-Pakistani war and spy films being made by Bollywood. However, a recent theatrical release by the name “Ikkis”, translated as “21”, shocked me. I was not expecting a sudden psychological shift in the Indian film industry…

Jan 30, 2026