Cue the Sun: DP Steve Yedlin on âWake Up Dead Manâ

Jan 8, 2026

Steve Yedlin and Rian Johnson on the set of “Wake Up Dead Man” (photo by John Wilson/courtesy of Netflix)

After spending the last Knives Out entry on a billionaire’s private Greek island, master sleuth Benoit Blanc’s latest mystery Wake Up Dead Man takes him to a remote parish in upstate New York to solve the murder of a priest (Josh Brolin). It’s a classic locked door mystery, with Brolin’s monsignor stabbed mid-mass in a closet a few feet from his pulpit. The suspects include a recently reassigned young priest (Josh O’Connor) and a tightly knit clique from the church’s flock (Jeremy Renner’s recently dumped doctor, Cailee Spaeny’s injured concert musician, Andrew Scott’s paranoid novelist and Kerry Washington’s lawyer).

Like every feature film Rian Johnson has made, cinematographer Steve Yedlin is behind the camera. With Wake Up Dead Man now streaming on Netflix, Yedlin spoke to Filmmaker about his love of zooms and his dislike for talking about lenses in “wine tasting terms.”

Filmmaker: What do you see as the connective tissue between all three Knives Out films? Are there elements of visual grammar that are intrinsic to the series?

Yedlin: Absolutely, but not from us making artificial rules for ourselves to follow, more me and Rian just trying to tell the story the absolute best visual way possible. That in itself is both why the movies look different and why there’s a throughline. On the one hand, these movies are so different. The last one was set in sun-drenched Greece in a big cement villa. This one is Gothic, and we’ve got a church and horror movie elements. So, you’re going to automatically end up with stuff that’s different. On the other hand, in all the films we’re solving puzzles with these big ensembles. In every movie you have scenes with a big cast of movie stars where they’re all in a room together and we don’t want to just shoot one person’s head and then cut to another person’s head. We have to communicate the dynamics between them. When you’re solving similar problems you’re going to end up with some aspects of it being the same, especially when it’s the same people doing the problem solving.

Filmmaker: What conversations do you and Rian have about the visual breadcrumbs you leave the viewer? Early in the film, you have close-ups of Jeremy Renner’s distinctive wedding ring and Kerry Washington tapping her spoon against her coffee cop. One of those plays a key role in the mystery and the other doesn’t. Are you intentionally weaving in misdirects? How do you not spoil the mystery while still making sure the audience notices all the details it needs to pick up on?

Yedlin: All of that comes from Rian. Even in the script it said that Dr. Nat’s ring is shaped like a nut so that we can recognize it. One thing that Rian always talks about is that the core of these movies all have to have an engaging story separate from the mystery and clues.

Filmmaker: Does this one have more zooms than the others?

Yedlin: I don’t think it has more zooms, but it has these very memorable endless zooms. The first one is when the groundskeeper Samson (Thomas Haden Church) is talking with Jud (O’Connor) in the garage about how Wicks (Brolin) inspired him to quit drinking. Over the course of that scene, we go from a ludicrously wide shot of not just the garage, but you can see the graveyard, the crypt and the house, then it zooms all the way into a medium shot of Samson. That was an idea Rian had. In prep I looked into what our options were because there is no cinema zoom that has that long of a range. We found a broadcast zoom mostly used for sports, like when they zoom in on the golf ball and then zoom all the way out. Panavision did some mechanical changes to it so that we could use it. The camera already had the right lens mount, but it didn’t have all the focus and iris control that we needed. Then you see that endless zoom again—a much faster version of it—in one of the flashbacks. I think they’re very memorable, but in terms of just the number of zooms, I don’t think it’s any more. Everything I’ve done with Rian–and a lot of stuff I do without Rian–has zooms. We use creep zooms a lot for intensifying. We also like to do a compound dolly zoom. We do have a dolly counter zoom in this movie, but more often we’ll do a compound zoom where we’re pushing in and zooming in to go faster.

Filmmaker: Do you have a director or DP whose use of zooms your particularly enjoy?

Yedlin: I mean, there’s not just one. I think zooms get a bad rap. It’s just another way to tell the story. Robert Altman does zooms that are much more what we think about when we think of 1970s zooms, where it’s a big reframe type of zoom. Those can be absolutely fantastic. He’s got evolving shots with all these characters and one thing turns into another and the zoom is reframing for the change. We actually did much more of that specific kind of zooming in the first Knives Out. I just watched In Cold Blood [shot by Conrad Hall], and it has these amazing zoom transitions where they’ll start zooming at the end of one scene and then be zooming in the first shot of the next scene and it’ll do a cross fade, which is an amazing transition. I don’t know why people don’t use it more.

Filmmaker: The first two Knives Out films were shot on the old Alexa sensor. Tell me about moving over to the Alexa 35 for Wake Up Dead Man.

Yedlin: I don’t think the camera is a very important leverage point in the look, but yes, the first one was Alexa Mini, the second one was the LF and this one was Alexa 35. The movie would’ve looked the same with any of them. That choice is more about checking boxes for distribution requirements that are based on legal definitions rather than actual image science. The Alexa 35 does have a different sensor and different spectral sensitivity, but I’m always mapping it to the look we want anyway. If anything, it’s just an extra step to prep the new camera to have our look, because we already have it set up for the old cameras.

Filmmaker: Did you use enhanced sensitivity mode or the Arri textures or any of that stuff?

Yedlin: No. I do the absolute minimal amount of processing in the camera because we’re going to do our own processing. This is going beyond Wake Up Dead Man, but I think the camera manufacturers are both bowing to and reinforcing—it’s a little bit of a feedback loop—this misconception that the camera is the leverage point for the photographic look. It doesn’t really matter what camera you use, as long as it’s good enough quality. There’s this ongoing superstition that the camera makes the look. Then because of that, the manufacturers have to say, “Well, ours has this look,” because everybody already believes it has a look and they’re making all kinds of new things to brag about, but it’s all just off-the-shelf processing instead of custom processing. We have the processing we want to do, and we’re not going to do some weird in-camera processing just because a new camera offers an automatic one. It’s the equivalent of using an Instagram filter instead of actually sitting down and colo-correcting the movie.

Filmmaker: Do you feel like the lens has more of an impact on the look than the camera choice?

Yedlin: I know a lot of people think about it that way, but I don’t think that the audience can see the lens model. We basically select lenses for flexibility. It’s like, “These lenses are fast. They don’t fall apart wide open.” Look, I hear great cinematographers who shoot great stuff talk about the lens giving the movie a look, that it’s going to give you certain kinds of skin tones or a certain warmth. They use all these kind of wine-tasting terms, but the reality is I don’t think the audience can see it. I know stories of people saying, “We’re going to shoot these characters with this lens model and these other characters with that lens model,” and they’re renting two entire lens sets that are really expensive. I’ve done tests and not only can the normal audience not see it, but most directors can’t actually see it. It sounds good when you talk about it, but in my actual testing that’s not something the audience can see. What the audience can see is that we did this shot deep into dusk that we wouldn’t have been able to do [on another lens set]. That’s dictated by the fact that we have a lens model that opens up almost as wide as any lens available, yet doesn’t fall apart wide open because every lens model is worse wide open. You’ve got to get off the bottom to get to its quality, but the difference is how [far from] the bottom you have to get and how bad does it get at the bottom. The lenses we used are the best for both of those. You only have to barely get off the bottom for it to be great and the most that it falls apart is way less than even the next best lens model. Sometimes when people talk about lenses in wine-tasting terms, they’d have you believe that only the junkiest lenses have interesting flares. Even the highest quality lenses are still physical objects in the real world. They’re not mathematically perfect things. So, in terms of getting something that has a texture to it and isn’t just clinical, literally as soon as you’re shooting with a real lens in the real world, you’re going to have that part of it.

Filmmaker: Let’s get into some specific scenes. The flashback is my favorite sequence in the film. The saturated colors feel like they’re out of a Mario Bava movie from the 1960s. Do you and Rian talk in terms of movie references when you’re prepping?

Yedlin: We might offhandedly throw things out, but we don’t sit there and look at movies. Rian and I have been friends and making movies together since we were 17 or 18 years old. We have a whole lifetime of talking about and watching movies together. References are always abstract anyway. Like, which aspect of this thing did you like versus which aspect did I like? To some extent, references are really just to make sure you agree with each other and have the same taste. At this point, we don’t need to do that. That flashback sequence just came from us designing those shots. I think we were just saying, “Let’s not be scared to go big with it.” The shot in the church with the red moon was something Rian knew he wanted from the beginning, I think even at the script stage.

Filmmaker: Was that moon done practically?

Yedlin: It’s a visual effect. We tested some practical things, but between what Rian actually wanted out of it and the fact that there was all this rain and everything, it ended up being a visual effect. We also did a thing in the flashbacks where we had these different cuts of these colored perspex, and Rian would arrange them in front of the lens. If it was right up against the matte box the crew would tape them down and if it was out a little further they would put them on a stand. It was to give us this idea of looking through stained glass. For some wider shots where we weren’t going to have the perspex and we were dollying fast, I proposed to Rian, “What if we continue with the unrealistic colors and I just make it completely red out the window?”

Filmmaker: For the high angle shot in the flashback where Wick’s mother is beating her hands against a mausoleum, is that a piece of set built in an exaggerated proportion? That’s a pretty cool shot.

Yedlin: No, it’s not even exaggerated. It’s just a really wide lens—I don’t remember specifically, but probably a 15mm. The Wicks engraving looks huge and it looks like she’s really far away, but it’s just a wide lens. It’s the same tomb set piece that’s in all the exteriors in the movie.

Filmmaker: I love a good character introduction and in this you introduce Wicks with a shadow. Father Jud is in the church looking up at the spot on the wall where the cross used to be, and the door opens off-screen and casts Wick’s shadow onto that wall. It felt like it could’ve come from some RKO noir in the 1940s.

Yedlin: That’s another shot Rian knew he wanted. I don’t remember if it was in the script or not, but it was absolutely known from the beginning of prep. It wasn’t any kind of improvisation on the day. The way we actually did those shadow shots was slightly different each time, but they were all totally low tech. You get a big light on the floor as far away as possible so the shadow’s sharp and you get the person who’s making the shadow unrealistically close to also help the shadow be sharp. Then the door is just a piece of foamcore or something.

Filmmaker: Cailee Spaeny’s character also has a memorable introduction, with this push-in behind her as she performs on stage with all these crazy flares.

Yedlin: We used a streak filter because Rian wanted a “glare of the lights” feel to it. It’s the only shot in the movie where we used that filter. What’s really fun is that the background is a cutout.

Filmmaker: So, you’re shining light through some sort of black backing?

Yedlin: Yeah, it’s just a flat, black backing with holes cut in it. In prep they kept moving this scene around. They were like, “We have this scene that’s in a concert hall, but it’s only one shot [where you see out into the hall]. Where are we going to shoot this? Where is it going to go in the schedule? It has to pair with something. We’re not going to spend one entire day and go to a concert hall for this shot.” Late in prep, I had an idea. There’s a shot of Bob Dylan from the mid-1960s where he’s on stage and you see this huge spotlight on him, and you just see the dots of whatever house lights are on. I was like, “We could do something like this.” I found some different references online and gave them to the art department and they made this large backing. It had to cover the whole background, but it’s just a flat cutout. They made all the holes in it, then our gaffer Dave Smith put lights behind all of them with some diffusion.

Filmmaker: Tell me about the church set. It looks gigantic.

Yedlin: That was an incredible set built by our production designer Rick Heinrichs and his team on C Stage at Leavesden Studios [northwest of London]. I told Rick it’s my favorite set I’ve ever shot, both because of how beautiful it is and how logistically shootable it was for us to do so many different looks in there. We had it rigged with two stage backings, which I asked the art department for. Instead of just a flat backing, there was a tree backing and also a sky backing that I could light separately so that we could get all of these really specific different looks. I could go full black on the trees and then a dim blue glow on the sky so I would get this silhouette of trees against sky. If it was full day I could front light and blast both of them until they’re not quite blown out but getting obviously overexposed. We could do dusk where I light the trees, but they’re dim and then the sky is brighter. Our gaffer Dave Smith really rigged the heck out of everything to where we could do all of these different looks as much as possible with just this custom light control software we were using. For the things that would have to physically move, he rigged those to be as quick and easy to move as possible. We had everything out there all at the same time. The big lights that were our sun were out there, but so were the softer lights for when it’s overcast. Over the top of the set there was not a completely solid hard ceiling. There were headers and in between each header were soft boxes that could raise up and down. In the giant wide shots, the soft boxes were all the way up or almost all the way up to get them out of the shot, but then if we were doing closer [coverage] we could bring them down lower.

Filmmaker: The movie has several important moments where you’re creating this effect that the sun is either ducking behind or popping out of cloud cover, including two pivotal moments in the church.

Yedlin: That was something where Rian knew exactly what he wanted in prep, that this sun is coming out behind Jud and flaring the lens as he is giving this swelling speech to Blanc about faith. So, Rian knew he wanted that, but on the other hand, it’s not like we knew in prep the exact mark where [Josh O’Connor] was going be standing. There had to be flexibility for us to figure out how we were going to do it with the exact blocking that happens on the day. Because we were set up for success by all the work we did in prep, I think the only large thing that we physically had to move that was rigged, as opposed to on the floor, was probably to adjust the light over a little bit or up and down on its batten. It was already out there, and we just had to move it a little bit for it to be exactly right there behind his head. And because everything is rigged and I’ve got our custom light control software, I can get immediate results. There’s no sense of the interface. I was able to finesse all this lighting. I don’t have to tell the gaffer and then the gaffer tells the lighting programmer, and we’ve got a game of broken telephone. I’m turning these knobs that are very gentle where I can change exact amounts of the lighting ratios and the exact color. As the sun comes out, I can change from warm to cool. I can dial it in exactly and also finesse the exact length of the cue. In the world of the movie, only one thing is happening—the sun is coming out from behind the clouds. In the real world of photographing the movie, a lot of different things are changing. The soft boxes are changing. The light on the backings is changing. The 20K that’s the sun is dimming up. So, we need to be able to finesse that cue where, on the one hand, it’s totally flexible and I can continuously adjust it. It can’t be the kind of thing where we’re like, “Well, this got programmed in prep and now it is what it is, and it can’t change.” On the other hand, it also has to be dependable and repeatable so that once we do get something we like, it can always start on the same line and take the same length of time from take to take. This is a huge performance scene for the actors, so we can’t be like, “So sorry. We messed up the lighting cue. Can you do that again?”

The other thing that was going on was we wanted all these lighting adjustments to feel like they were one cue, but sometimes the lengths [of each lighting change] had to be very, very different. Everything was LEDs except for [the light serving as our] sun, which was an incandescent 20K. That light has a very different dimming reaction than LEDs do. So, the cue for the 20K might have to technically be 50 seconds long for it to feel like it’s 30 seconds because you can’t see some of the dim curve. Some of the LEDs might even have different durations than other LEDs for it to all feel like it’s the same cue.

Filmmaker: That’s all in a controlled environment. You have one of those light changes in the woods as well with Father Jud in a wide shot. How do you pull that off away from the confines of the sage?

Yedlin: With all those light changes in the movie, there was exactly one time where it was pure luck and it’s that shot. The sun actually just came out and Rian and I looked at each other like, “This is unbelievable.” Depending on whether you [share the worldview of] Blanc or Jud, either we got lucky, or God gave us the exact thing we wanted.

Publisher: Source link

The Housemaid Review | Flickreel

On the heels of four Melissa McCarthy comedies, director Paul Feig tried something different with A Simple Favor. The film was witty, stylish, campy, twisted, and an all-around fun time from start to finish. It almost felt like a satire…

Jan 30, 2026

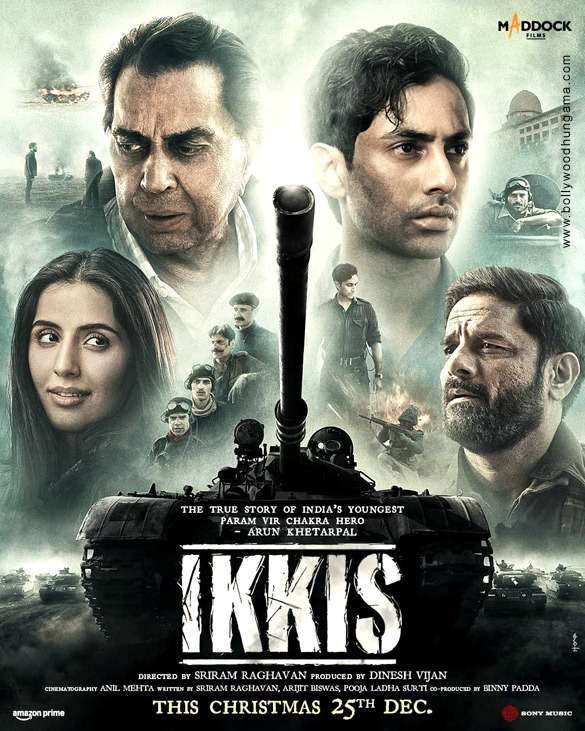

The Legacy Of A War Hero Destroyed By Nepotistic Bollywood In “Ikkis”

I have seen many anti-Pakistani war and spy films being made by Bollywood. However, a recent theatrical release by the name “Ikkis”, translated as “21”, shocked me. I was not expecting a sudden psychological shift in the Indian film industry…

Jan 30, 2026

Olivia Colman’s Absurdly Hilarious and Achingly Romantic Fable Teaches Us How To Love

Sometimes love comes from the most unexpected places. Some people meet their mate through dating apps which have gamified romance. Some people through sex parties. Back in the old days, you'd meet someone at the bar. Or, even further back,…

Jan 28, 2026

Two Schoolgirls Friendship Is Tested In A British Dramedy With ‘Mean Girls’ Vibes [Sundance]

PARK CITY – Adolescent angst is evergreen. Somewhere in the world, a teenager is trying to grow into their body, learn how to appear less awkward in social situations, and find themselves as the hormones swirl. And often they have…

Jan 28, 2026