From Mail-Order to Online: Tom Davenport on Founding Folkstreams, the Pioneering Online Streaming Site

Nov 29, 2025

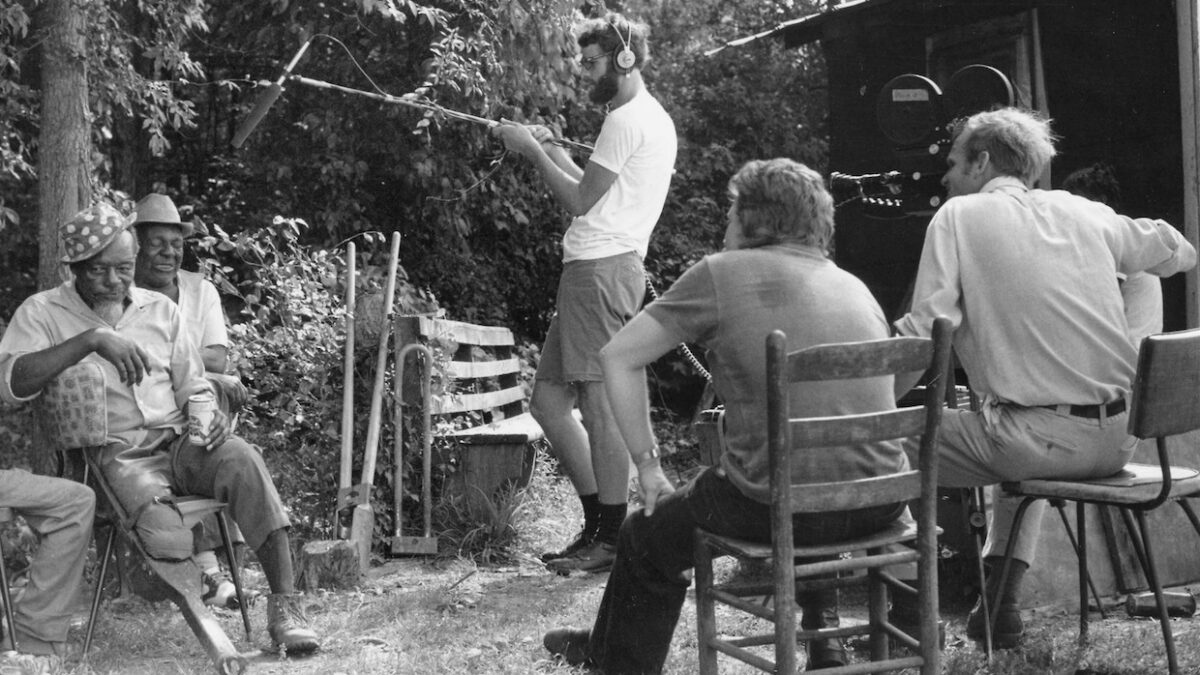

Tom Davenport filming Born for Hard Luck

When I first discovered the works of Jean Rouch, Robert Gardner, and Timothy Asch—academic anthropologists who opted to make films rather than books about their research subjects—my appreciation of their work was hampered by some lingering questions: “How in the world did they distribute this? Who paid for this? Who was watching this?” Sure, the government pays for them, universities buy them and academics screen them for students, but these filmmakers are also studied and appreciated within cinephile circles in a way that, say, 1940s newsreel directors are not. How did these filmmakers find an audience outside the ivory tower? Since this academic model of production and distribution exists independently of the wider film economy, answering that question may open new (or old) pathways for independent filmmaking.

Then, I found Folkstreams, a website that exclusively hosts documentaries about American folkways and folklore. The films are sometimes academic, as they’re the work of professional anthropologists and ethnographers. Others are works celebrating American folk art and culture, where the amateurish production is directly proportional to the film’s love for its subject. The films typically range anywhere from two minutes to two hours, and not a single one is “marketable” in the traditional sense. Yet here they are, completely free to watch. This is largely thanks to the continuous work of filmmaker Tom Davenport, who founded Folkstreams in 1999 in order to serve these films’ niche market and further expand their audience. That Davenport could watch these videos in primitive codecs on a dial-up connection and still feel that this was the future of independent film distribution speaks to his powers as a soothsayer.

At 85 years old, Davenport still maintains Folkstreams daily from his Virginia home. I brought up my pedantic queries about academic film markets; Davenport, in quintessential Folkstreams fashion, answered with stories about his life and career that provide a glimpse of what truly independent filmmaking in the 20th century was like. He’s quick to admit that he was lucky to live in a time of free-flowing grants and endowments—the very same that would eventually fund Folkstreams, and the very same that are currently on the political chopping block. We may need more than luck to continue his vision.

Filmmaker: I was reading that you got started in your filmmaking career by working alongside D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock. I’m curious about in what capacity you were working for them and whether or not they were an influence on the films you would later make.

Tom Davenport: They certainly were an influence. They were the rebels in town when I arrived in New York. Ricky Leacock had just worked with Robert Flaherty as a cameraman on Louisiana Story. They both had an engineering background and were very excited about hooking up their Auricon 16mm cameras to Nagra tape recorders with a sync mechanism that ran on a tuning fork that kept everything in sync. So, you didn’t have to have an umbilical cord between the camera and tape recorder, and you could have a very different kind of movement in the way you filmed. I got interested in what was called in those days cinéma verité. I remember Pennebaker saying once that when you were filming it’s better when you didn’t even look through the viewfinder. You disappointed the camera. It was unlike framing Nanook of the North or those early documentaries made by the Farm Security Administration during the Depression, like The Plow That Broke the Plains.

Filmmaker: What was your impetus to begin making films with Dr. Daniel Patterson, the head of the Curriculum in Folklore at University of North Carolina?

Davenport: After poking around New York for a couple of years and doing freelance work, I decided I’d go back to Taiwan, where I had been a student of Chinese language, and start taking pictures. I had a contact [through] my parents at National Geographic, and they set me up with all the film I needed and development. They said, “We’ll let you go. We’ll give you a small stipend. You can go out there, start taking pictures and we’ll review them for you.”

I was out there for about six or seven months working hard, then got a letter from National Geographic that said, “We’re terminating your work. Thank you very much. We’re sending our professional team out there to finish the job.” I did manage to get some pictures into that article, but the feeling of depression set in—here I’d spent all this time taking this big gamble and I was coming back with nothing.

But when I was out there, a guy introduced me to a Chinese Zen teacher who happened to do Tai Chi, something unknown in the West at that time. They had a camera at the United States Information Agency in Taipei, which I was able to borrow. So, I went out and shot this footage of Nan Huai-chin doing T’ai Chi Ch’uan on a big rock on the coast. When I developed the 16mm footage, I came back to the John D. Rockefeller Foundation in New York, which had an interest in promoting artistic exchanges between Asia and the United States, and it just happened that one of the officers in charge of that foundation, Porter McCray, was from [my home state of] Virginia. He took a liking to me and said, “Yes, we’ll give you a small $5,000 grant to make this film.” So, I made [T’ai Chi Ch’uan].

When I was in Taiwan and got interested in Zen, I was trying to find antecedents in the United States for that kind of religious expression outside of Christianity and traditional Western religions. I happened upon a book of photographs of the interiors of Shaker buildings and furniture. The way they were photographed was very stark; they looked like Japanese temples in their simplicity. I contacted a friend of mine in New York, Frank DeCola, who I’d worked with as a freelance photographer. Frank was able to get this money just to make this 35mm black-and-white film on New Orleans jazz, The Cradle Is Rocking.

Because of his interest in music, Frank was very interested in Shaker music, and the expert on that was a guy named Daniel Patterson in Chapel Hill. I wrote to him and said that we’re interested in doing a film on the Shakers. Anne Rockefeller, who Porter McCray introduced us to when he heard that we were interested in that, gave us a $5,000 grant to do a film on the Shakers. So I started this film with Frank. Before we had even finished all the photography, Frank got a brain tumor and died. So, I ended up having the responsibility of finishing the film, and Dan became a collaborator. He was very, very excited about the idea of film documentation. That first film with Dan was The Shakers. It’s a sort of conventional film with narration by me, because we didn’t have much of a budget. That led to a series of films that we did in collaboration with the UNC folklore curriculum, and that’s how I got to know Dan better. I’m still very much in touch with him. He and his wife Beverly are in Chapel Hill. He’s 95 years old now. But he’s still a very, very good advisor and very bright about a lot of things.

Filmmaker: What was it like to produce, get money, secure equipment and try to distribute these movies in the ’70s and ’80s?

Davenport: When I made the Shaker film, my wife and I got married and moved down here to Virginia where my father had an old house on the farm that he was able to fix up. He did some housing developments around Alexandria that were very mid-century modern called Hollin Hills, and he bought this farm with the money that he made. After my wife was pregnant, we moved into the house, as it was so much cheaper to live where I didn’t have to pay any rent. I moved my Steenbeck down into the basement and we edited The Shakers, since we had that small grant. The National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities had just started and were giving money to filmmakers to make films. It wasn’t very bureaucratic at that time. Subsequent to that, for most of the films that we did, we were able to raise money through the National Endowment or state counterparts. Folkstreams is really a product of that too, because we’ve been supported by both the National Endowment and the IMLS [Institute of Museum and Library Services] until recently, when they rescinded everything. But we were lucky; the timing was right for that, and those endowments really spurred on a tremendous amount of creative filmmaking. As time went on, it became more bureaucratic and [that] weakened it a little bit, but in those days it was very active and very creative.

Filmmaker: That does sound like a dream these days. Did these endowment programs have a particular kind of audience in mind for the films they funded or guidelines for filmmakers to distribute these films? Did you have a particular audience in mind whenever you were making these films?

Davenport: It was influenced at that time by the way in which these films would be delivered. With a 16mm [print], you’d sit in a room like a theater and play them. We were able to distribute them ourselves. When I moved down to Virginia, I had this bright idea that I would just self-distribute the films like I was selling some folk art or handmade rugs through mail order. In those days, the only people that would buy them were public libraries and universities. If you sold a 16mm film, every sale, in today’s money, was about $5,000—if you sold 20 films, that was a lot of money. So, we would just advertise the films and do mail order. Les Blank made a living pretty much by doing that and several of us followed. Now that’s all changed because of the proliferation of YouTube and streaming services. It’s very difficult to have a film now without raising money to make it. I suppose some of these films do make money, but to me it’s hard to imagine.

Filmmaker: Yeah, I think something like 80% of independent films don’t break even. You were saying earlier how these programs have become more bureaucratic. In what other ways has the process of making ethnographic documentaries changed?

Davenport: In those days, there were essentially four broadcast networks: ABC, NBC, CBS and PBS. PBS had just started very much in tandem with the interest in the National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities. Other stations wanted their own people at the station to make their films. They weren’t going to sign a contract with an outsider like myself, but PBS was willing to do that. If you had a good film and they liked it, they would buy it and put it on there. They liked The Shakers, so we got a national broadcast with that on PBS. But you’d also have to be thinking about the runtime, making films that were 57 minutes if they were for PBS or maybe 50 minutes if they were on NBC, because they had advertising. If you made a film that was 17 minutes long, there wasn’t a chance you’d get a broadcast. But a lot of independent films, like the films of Bill Ferris, they’re odd lengths like that, and a lot of my early films were that way too. They were independently made with the endowment money usually, or small grants, but never could get shown on any of the networks. That was a stimulus for starting Folkstreams.

Filmmaker: Was there a particular moment that caused you to think that somebody needed to collect all these films and have this online archive? 1999 is a very early time to start putting lengthy videos on the internet.

Davenport: One of the fairy-tale films that we did in the mid-90s was Willa: An American Snow White. PBS told us that they would broadcast it, but, at that time, they said that you had to have a website. And to make a website, they said, was extremely expensive—about $50,000. So, my wife Mimi, a very talented artist who did all the costuming and co-produced all the fairy tale films, said, “I think I can figure that out.” She bought some books about how to do it and made a website. So, I said that if we make websites for our films and other Folkways films, we could put these films up, and they could find a niche market. Maybe not everybody’s interested in a work about a tinsmith or a particular blues singer, but plenty of people will be interested if you find that niche market.

That thought grew into the idea of Folkstreams. But in the early days, we thought we had to make a separate website for each individual film. Can you imagine how much work that would be? If you wanted to make a change, you had to change every single thing in the code; you couldn’t just create a template which is fed by all the data that you gathered on a film. I contacted a guy named Steve Knobloc who was working on PHP programming that could fix this. He developed the first site for Folkstreams. It was a technical struggle. In those early days we had some help from an organization at Chapel Hill called ibiblio, an Internet site that basically tried to become the world’s biggest library of everything. Paul Jones, who was running that, became an advisor for Folkstreams because we were connected with Dan Patterson. About ten years ago we adapted it to a much more robust system, but that’s how we started off. We were very early: Folkstreams predated YouTube, but Folkstreams is different from YouTube in the sense that we’re curated. It’s not a technical system.

Filmmaker: I’m curious how Folkstreams operates day-to-day. What does the team look like and what’s needed in order to maintain a site like this?

Davenport: Basically, it’s mostly me now and I think about it all the time. I have to get away from it in order to keep my sanity. Obviously, I have some technical help with new software that we use to carry the site, and a couple of people are very helpful in terms of technical questions that I can’t answer. I correspond, of course, with all my advisors and the filmmakers themselves. This past week, we put out a little newsletter, which is infrequent, and I update and patch things constantly. The problem in the long run is that nobody knows the site as well as I do while also knowing the technical side of it. I think Dan Patterson and his wife Beverly know a lot about the films and their content, but they don’t know anything about how they go up there. Then there are many new films [for Folkstreams] that have come in, so I had to create transcripts and correct captions. It’s very mundane work. It takes a lot of work to put a film up and make sure that all the information is correct. You have to go back and forth with the filmmakers, and they can be very particular about certain things.

Filmmaker: How would you categorize the kind of films on Folkstreams? “Folk” in the name probably gives it away, but I’m curious if there’s criteria you’re looking for in docs about folklore or folkways.

Davenport: People sometimes come to me and say, “Well, this is a film about folklore,” and the film is just a band on the stage with the camera on the floor and they’re taking a picture of that performance, or they have a picture of a guy doing some kind of craftwork and that’s all it is. It shows how he formed a metal or forged the object that he’s working on, but it doesn’t tell you much about the person and doesn’t tell a story. Almost all of the films on Folkstreams tell a story. One of the basic things about them is that they show you how folklore, in its broadest sense, allows people a survival story. It’s what got them through hard times or a personal crisis in their lives. They’re not just clips or performances or demonstrations or how-tos. YouTube’s great. It’s got a lot of stuff like how to fix a 1929 Ford or something like that. We don’t show that kind of film.

Filmmaker: Back in the ’70s and ’80s, were you aware of the need to archive a lot of these films that you were making? And is that a process that Folksteams is involved with now?

Davenport: When I was younger I didn’t care about that as much. As you grow older, naturally you think about archiving your material and that somebody might find use for it. I kept most of my 16mm material here in my office, but the University of North Carolina was interested in a lot of my materials, especially the documentaries, because of the Center for Southern Folklife Collection that Dan Patterson had been instrumental in starting. It’s a special library where they’re primarily collecting music, but they collect films as well.

When you get into the archiving business, you realize that there’s this vast amount of material that’s produced, especially when you’re shooting digital material which doesn’t cost anything; when you were shooting film, that was tremendously expensive. If you shot a 10-minute roll of film, got it developed and then made a work print from it, it would probably cost about $500 in today’s price, so you didn’t shoot as much. Your ratio of shooting, instead of one part out of a hundred, might be one in five or one in ten in terms of what you’d be from your final film. This tremendous increase in materials has created a lot of problems in archives: how you catalog it and find it, whether it’s in digital form or not.

Folkstreams decided at one point that we could keep all our archives at the University of North Carolina in their library system, but it soon became apparent that the filmmakers that I contacted for Folkstreams were all over the country and had their material in other archives. So, we decided to create a section in the database called “Archives,” where you would note where the archive was, and any kind of information you could gather from that archive. You could check it if you wanted to go back and find original materials, or in certain cases you might want to re-digitize an old film that you only have a very poor copy from. Maybe the only copy that’s running on Folkstreams comes from a VHS; if it was a 16mm film, that means that you could have had a much better higher quality scan or stream if you go back to the original film.

The National Film Preservation Foundation in California gives grants to libraries and people restoring films. If you write a proposal and feel that the film is in danger, they will give you funds to rescan it. But it has to be a very endangered film—maybe it only exists as a print or a negative that has been damaged somewhat. Then they’ll have you restore that. It’s an expensive, lengthy process. I’ve worked on a couple of these things where you go to the lab and they’re scanning every frame and building the film back up. We have several restorations that we’ve done. And we encourage that; it’s helped filmmakers who are worried about that.

Filmmaker: Does the grant fully cover the process?

Davenport: Those grants only pay for billable lab work. They don’t pay you for overseeing it, discovering the film, putting the film up on Folkstreams or anything like that.

Filmmaker: If there’s one person who feels like a celebrity figure of the Folkstreams genre, it’d probably be Les Blank. I’m curious what your relationship with him was; do you think his fame overshadowed other filmmakers working like him or did his work help highlight this style of filmmaking?

Davenport: He’s a very important and talented filmmaker. Before Les died, he was, again, very careful about his legacy and how his films were distributed, because he was making a living from that. So, he told me, “I want to put up a couple of films on Folkstreams and see how it affects my own distribution.” Because if they’re available for free on Folkstreams, why would anybody buy any DVDs? That was what he was thinking, I think. So he gave us some films that he wasn’t selling very much of, and they play on Folkstreams.

Meanwhile, because of his sorta-celebrity status, he was able to land some contracts with companies that digitize and sell streaming rights to universities and public libraries. I think one of the examples would be Alexander Street and Kanopy. After he died, his son Harrod was distributing these, and I said to Harrod, “Are you making any money from these to make it worthwhile for you?” He said he really doesn’t make much, maybe $5,000 a year. But he still didn’t want to give us the rights to that because he’s very much into distributing his father’s legacy; Harrod’s also a filmmaker himself. So, we never had been able to get a lot of Les Blank films. That’s the one hole in Folkstreams, I think. But we try to steer people to them through the films that we do have of his.

Filmmaker: We have many experimental ethnographic films, like the works coming out of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, in international film festivals today. But what were ethnographic filmmakers’ relationships with film festivals like in the ’70s and ’80s?

Davenport: Because the only people that bought the films were public libraries and university libraries, they would have the American Film Festival, which was a huge event, usually in New York City, where librarians would gather and screen these films in different categories. Another similar thing was the CINE Golden Eagle Awards, where there were competitions. So, if you got that award or a Blue Ribbon at the American Film Festival, you were almost assured of having pretty good distribution among librarians and could budget the purchase of that film because of that. But those festivals don’t exist any longer. Right now, there are so many festivals, and they are costly to enter. They require entry fees on your part and a lot of people just don’t go to the theater as much.

I tell filmmakers that if there’s a film that looks like it’s going to be a folklore film that would be good, don’t give it to us on Folkstreams. Try to distribute it for the next three or four years and see what happens. You usually get a little bump from it. If you win a prize at a festival, you might indeed get picked up by something like Netflix or Amazon Prime, which would probably give you some front money on that thing. I distribute some of my films on Tubi and put advertising in them, and the advertising pays a certain amount that goes to the filmmaker. I spent a lot of time doing my children’s series for Tubi, but my returns on that work were negligible, really. I think I made $500 last year. As a filmmaker, they don’t want to deal with you. They want to deal with somebody who says, “I’ve got 10 or 20 films I want to sell to you.” Most of the time the filmmakers coming to us now are ones that have films they realize have no commercial value any longer.

Now, Folkstreams does function as a source for stock footage. That’s one of the things that helps fund Folkstreams, and probably the most popular films that have been used in other films are the films of Bill Ferris. The other interesting filmmaker, who’s been very helpful to Folkstreams and a very interesting character, is Steve Zeitlin and his work with City Lore in Manhattan. He’s been very successful. We have a bunch of films from City Lore on Folkstreams as well as a bunch of Steve’s own films. And Steve has a son [Benh]. He did a film that was nominated for an Academy Award a few years ago, [Beasts of the Southern Wild]. Steve Zeitlin himself worked with a filmmaker named Paul Wagner to do a film called The Stone Carvers, about these Italian stonemasons who helped build the National Cathedral. Steve’s one of the most prolific filmmakers on Folkstreams now, and he has been very successful in getting grants for things. He recently sold his collection, I think, for some big bucks to the Library of Congress’s archives, because they felt they had so many films from people in very rural areas and wanted some city folk art.

Publisher: Source link

Timothée Chalamet Gives a Career-Best Performance in Josh Safdie’s Intense Table Tennis Movie

Earlier this year, when accepting the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role for playing Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown, Timothée Chalamet gave a speech where he said he was “in…

Dec 5, 2025

Jason Bateman & Jude Law Descend Into Family Rot & Destructive Bonds In Netflix’s Tense New Drama

A gripping descent into personal ruin, the oppressive burden of cursed family baggage, and the corrosive bonds of brotherhood, Netflix’s “Black Rabbit” is an anxious, bruising portrait of loyalty that saves and destroys in equal measure—and arguably the drama of…

Dec 5, 2025

Christy Review | Flickreel

Christy is a well-acted biopic centered on a compelling figure. Even at more than two hours, though, I sensed something crucial was missing. It didn’t become clear what the narrative was lacking until the obligatory end text, mentioning that Christy…

Dec 3, 2025

Rhea Seehorn Successfully Carries the Sci-Fi Show’s Most Surprising Hour All by Herself

Editor's note: The below recap contains spoilers for Pluribus Episode 5.Happy early Pluribus day! Yes, you read that right — this week's episode of Vince Gilligan's Apple TV sci-fi show has dropped a whole two days ahead of schedule, likely…

Dec 3, 2025