Guy Maddin and David C. Roberts Discuss âSong of My City,â City Symphonies and the âVivisectionâ of Cinema

Jan 10, 2026

Song of My City

Steam pouring from manhole covers, the neon-lights of 42nd street seen through rain-streaked taxicab windows, phalanxes of cops spied from tenement rooftops as they sweep a city block — David C. Roberts’s Song of My City distills the visual rushes of a score of 1970s and early ’80s New York City-set film classics into a 15-minute city symphony of sorts. Drawing inspiration from 1920s pictures such as Walter Ruttman’s Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis, Roberts has pulled shots from Taxi Driver, Dog Day Afternoon, Across 110th Street, The Warriors in order to capture not just ’70s New York but the sense memories of movie viewers whose images of the city are forever shaped by the way it’s been imagined by a particular generation of filmmakers. In the below conversation, Guy Maddin, a filmmaker whose has employed similar collage techniques in films like The Green Fog, chats with Roberts about cities, the ’70s and finding a sense of place in the edit room. — Scott Macaulay

Maddin: Lo and behold, you did it. You made this magnificent Song of My City. It’s completely different in tone from The Green Fog, but it’s using the same strategy. It’s pillaging, strip mining, repurposing footage from a particular vein. In my case, it was a Hollywood film shot in the Bay Area. Yours was New York of a particular vintage, and what a great idea, what a motherlode of imagery, what a motherlode of emulsion — New York produced in the ’70s for our delectation.

Roberts: Thanks a lot, Guy. You know, I grew up in Alabama. I didn’t come to New York until I was probably 20, 21, but I started watching these movies — Taxi Driver, Dog Day Afternoon… — in seventh grade or eighth grade. That cinematic setting was so foreign to me but so exciting. I felt like I knew the streets, and how they worked. The purpose of Song of My City was to recreate that vibe I had as a child. What was my New York before I went to New York?

Maddin: The Mythic New York rather than the real New York.

Roberts: Yes, the mythic New York. I had this idea percolating in my mind since I started in films [of] trying to capture this memory of a dream. But it wasn’t until recently, a couple of years ago, when I was watching these old city symphonies from the 1920s.

Maddin: Berlin?

Roberts: Berlin. Yeah, Berlin. They had a couple in Paris, one in Nice. It depends how you define it. Man with a Movie Camera could be called a city symphony.

Maddin: Yeah, I think of that as one. A Soviet city that’s just many cities.

Roberts: Yeah, it’s cheating a little bit. It doesn’t use just one city. But it’s the same thing with this day in the life of a city

Maddin: From dawn until bedtime.

Roberts: Exactly. And when I saw Berlin, I thought that’s it. That’s what I needed. I wanted a day in the life of this mythic city, created from the B-roll of these films. I went to my wonderful editor, John Sears, and I said, “I think we can do this. It’ll take a couple months, right?” I’d already had a script written with all the clips I wanted to use and had a song in mind: Steve Reich’s “Drumming.” Well, it took us about a year.

Maddin: Let’s talk about that for a second. When did you decide the organizing principle would be night, then morning, then brightness of day and then night again? Is that basically your organizing principle?

Roberts: We initially tried the Berlin organizing principle, which was “morning, midday, afternoon, evening.” This is how the city symphonies typically worked in the 1920s, but it just didn’t work for us because the New York ’70s movies were really night kind of films.

Maddin: Nocturnal grit.

Roberts: Yes. It starts in the night and it’s quite menacing in some ways. We use this Philip Glass song called “Clouds,” which has a sense of awe, but is also ominous. And so you had these menacing scenes…

Maddin: It’s perfect, it’s perfect. Glass is put on this planet to score nocturnal New York Street scenes because the movie flows really beautifully. It’s a celebration. Since I became a filmmaker, I didn’t just notice stories in movies and acting or more acting, as the Academy Awards like to reward, or louder sound mixing instead of best sound mixing or whatever. I just noticed the emulsion and the grit, and I almost can’t tell the difference between the chemicals in the film emulsion and the chemicals that the denizens of New York are inhaling or the night fluids that are just hanging suspended in the air, the exhaust, some really strong armpits flying around. So the garbage, the urine town smells, it’s all just mixed together in the emulsion to me, and I just can’t imagine New York looking as good, even if someone with a big budget set out to make a New York movie set in the ’70s today, they couldn’t pull it off. And you’ve concentrated all these chemicals. You’ve made the janitor-in-a-drum version of New York in the ’70s. If someone wants that experience, it’s there, 16 minutes worth, and man, you get it.

Roberts: It’s got to be one of the best cinematic settings ever.

Maddin: I’m so glad you made it after we made The Green Fog, which is a kind of San Francisco city symphony. Its organizing principle is that it’s a remake of Vertigo. We had so much fun making it, but we thought we wanted to make more city symphonies. So I approached some friends at the Berlinale about doing Berlin, an update of a Berlin City symphony. I thought of New York, I thought of Paris, but then all the movies would be in French.

To me, San Francisco seemed to be the best thing we could ever tackle as a subject because the subject of Vertigo itself is a man maniacally obsessed with the myth of a woman and he’s remaking her. So it’s what we were doing with the film, and then we got daunted by the challenge of New York, but you found exactly the right tack somehow, the New York of your childhood , and the New York that most people think of when they think of New York. I think it’s the New York everyone wants to see as long as they don’t get hurt when they go visit it.

Roberts: I live here in New York now on the Upper West Side, and I talk to these old-timers here, and there’s such a nostalgia for the ’70s. And then they start telling me stories about how you couldn’t walk on the sidewalks at night. There was dog shit everywhere. The stories are about a city you would never want to live in, and yet there’s this nostalgia.

Maddin: Well, because they survived it — it’s like war veterans.

Roberts: Yeah. I have nostalgia for that period, but I went to New York for the first time in 1999 or something. I have nostalgia just from the films.

Maddin: That’s more important, though, because you’re making a film essay or a film symphony and your nostalgia comes from film and you don’t even have to capture the truth. It is the truth. The instant you cut one shot to another, it’s the truth. It’s your truth.

Every now and then you split the screen up and you start messing with it formally, and that’s pretty cool how you did it. Was that just a matter of the movie needing a change of pace here, and this was one way to maybe just keep the eye alert, keep the eye on top of things? Because even as spectacularly cinematic a city as New York, if you’re making a cinematic poem about it, you got to use all the tricks in the bag as a filmmaker.

Roberts: That is John’s genius. John is a genius with graphics. And one of the reasons I love working with him is that other editors I work with often only do the things I tell them to do. “Hey, this is what I need.” And then they’ll give it to me and it’s fine, it’s good. But John, he brings new ideas, and a lot of them don’t work, but goddamn, some of ’em do.

Maddin: I love them. They work well. And especially these bands of high-angle shots of the streets where at first you’re not even sure they are three different bands, they just seem like the same thing. And then your eyes are familiarized, but you don’t know it at first. And there’s a really fun one where a subway train above ground is divided up and its doors slide open, but the different sections of the screen, the Brady Bunch screen, are delayed somehow and the door gets to open on a variety of timelines. It’s just so beautiful and it goes with the music.

Roberts: I wish I could take credit for that. That was John. He is a genius for that type of stuff.

Maddin: It’s nice to hear you crediting your collaborator because film editors are filmmakers too.

Roberts: Absolutely.

You know, my wife asked me, why do you use these collage techniques? I am drawn to them by your film, The Green Fog, and Los Angeles Plays Itself by Thom Anderson — I don’t know if you’ve seen that one, that was a huge inspiration for this. And another one — I think one of the great pieces of art of this century‚ was Christian Marclay’s The Clock, where he’s doing a 24-hour version of nothing but scenes of timepieces.

For me, those three collage films were pure magic. You have many different layers of experience. You’re experiencing a clip at one level where you recognize where it came from, like, “Oh, I remember that film with James Cagney.” At the same time, you’re experiencing this whole new story that the filmmakers made. So you’re hyper alert in some ways, but in some ways, as you’re going through, you’re not. When I saw those films, including your film The Green Fog, I just thought that’s something that I got to try. That’s the magic.

Maddin: Thank you.

Roberts: So what draws you to these collage films, Guy?

Maddin: I make a lot of just paper collages too. I just like a surprising collision. When you watch these repurposed film-movies like you and I make, you do become hyper alert to every edit, and you’re always pleased when an edit works. And because we’ve got good editors — my partners are my editors, and they make sure the cuts work. Sure, you forget the cuts for a while, but because you’re cutting across different movies and different years and things like that, you’re aware of the cuts all the time.

And when cuts work, I dunno, it’s like a vivisection, but not a cruel one. A vivisection of cinema and how it works. And so you’re not only enjoying the movie for what it is, but you’re wide awake to… it’s like you’re on an extra high plane of awareness or something when you’re watching these things.

David C. Roberts is a former diplomat and academic physicist, and currently a filmmaker/writer based in NY. His articles have appeared in the NYTimes, Atlantic, and the Wall Street Journal. Song of My City is currently streaming on HBO Max and will premiere on Turner Classic Movies on January 21 alongside several of the films from which the filmmakers sourced clips.

Publisher: Source link

The Housemaid Review | Flickreel

On the heels of four Melissa McCarthy comedies, director Paul Feig tried something different with A Simple Favor. The film was witty, stylish, campy, twisted, and an all-around fun time from start to finish. It almost felt like a satire…

Jan 30, 2026

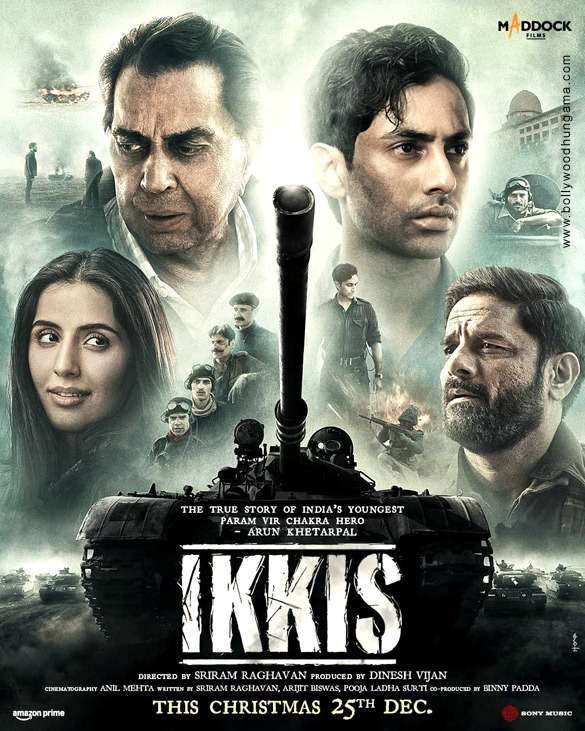

The Legacy Of A War Hero Destroyed By Nepotistic Bollywood In “Ikkis”

I have seen many anti-Pakistani war and spy films being made by Bollywood. However, a recent theatrical release by the name “Ikkis”, translated as “21”, shocked me. I was not expecting a sudden psychological shift in the Indian film industry…

Jan 30, 2026

Olivia Colman’s Absurdly Hilarious and Achingly Romantic Fable Teaches Us How To Love

Sometimes love comes from the most unexpected places. Some people meet their mate through dating apps which have gamified romance. Some people through sex parties. Back in the old days, you'd meet someone at the bar. Or, even further back,…

Jan 28, 2026

Two Schoolgirls Friendship Is Tested In A British Dramedy With ‘Mean Girls’ Vibes [Sundance]

PARK CITY – Adolescent angst is evergreen. Somewhere in the world, a teenager is trying to grow into their body, learn how to appear less awkward in social situations, and find themselves as the hormones swirl. And often they have…

Jan 28, 2026