How Do You Take America’s Worst Home-Grown Terrorist and Make a Movie Like This?

Mar 21, 2025

Of all the questions that Mike Ott’s McVeigh leaves hanging, of all the threads of conspiracy and unspoken ties to the current political and administrative actions of the USA that are awkwardly hinted at yet never truly engaged with, there’s one query that, for a reviewer of film, is perhaps the most salient: Do we, in fact, need this film to exist? It’s not as if The Bin Laden Story, focusing on the Saudi’s perspective, is soon to show up in multiplexes (though, quite honestly, that’d make for a far more fascinating portrait than those that take a different tack), so why do we need a film that humanizes, at times even sympathizes, with one of the most monstrous people in the history of America?

Timothy McVeigh was the perpetrator of a mass killing that raised unheeded alarm bells about the rising tide of radicalization from a massively vocal subset of the country that continues to wreak havoc to this very day, with the very same dark ideas of hatred being fueled by those at the highest echelons of political and religious life. For some, he is an anti-government hero, for others a sad little man with delusions of grandeur, while for others, he’s not thought of at all, the events of decades ago supplanted by even more grand acts of violence. McVeigh himself, in Mike Ott’s direction, and with the script co-written by Alex Gioulakis, is a dull, even gormless man constantly staring off to the distance, his vacuousness belying the plans for brutality that we only see in flashes at the film’s conclusion.

The Oklahoma City Bombing Falls Like a Dark Shadow Over ‘McVeigh’

The morning of April 19, 1995 was a sunny one, a peaceful day as any other. Unnoticed by just about everyone who went to work that morning, the date coincided with the second anniversary of the debacle in Waco, Texas that saw the death of a Christian cult leader who refused to acquiesce to lawful arrest, whereby he allowed and even encouraged many of his followers, including children, to be immolated as a form of delusional martyrdom.

Army veteran Timothy McVeigh had witnessed the showdown with the FBI at that Texas compound. Now, 24 months later to the day and fueled by poisonous racism, a Christofascist ideology, and fervent right-wing anti-government radicalization, the most lethal domestic terrorist in American history set the final parts of his plan in motion.

Driving a cube van containing thousands of pounds of explosives McVeigh had acquired thanks to his Army buddy Terry Nichols, the 27-year-old parked the truck in front of Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. After the detonation, some 167 people were dead, including federal workers and nineteen children who were ensconced in the on-site daycare center, while almost 700 were physically injured.

‘McVeigh’ Loosley Looks at the Events That Led to a National Tragedy

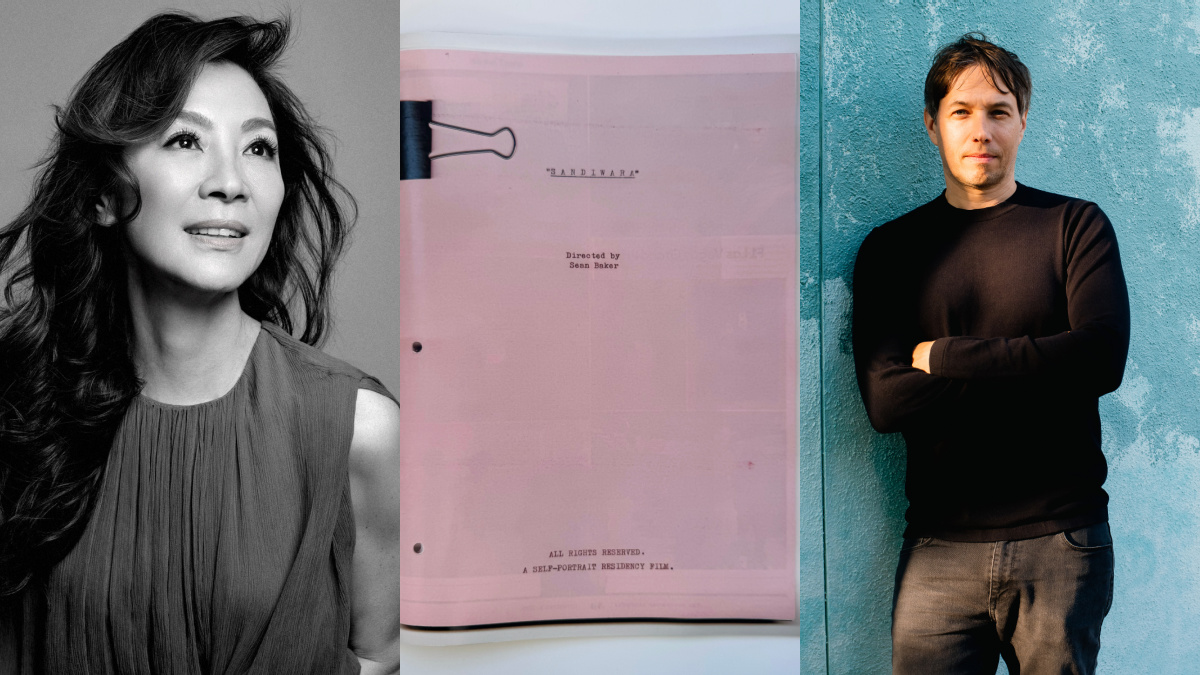

Image via Decal

Ott’s film only touches upon the bombing itself through a brief epilogue, where news footage is assembled in a chaotic, even experimental fashion, with flashes of witness statements from the bombing, testimony about the Waco raid, and even scenes from Waco itself moving backward and forwards in a swirling mass. The lead-up to this kinetic finale is far slower, deliberate, and at times even excruciatingly dull, reveling in the somber tone as we see McVeigh, piece by piece get the materials together for the eventual explosion.

McVeigh is portrayed by Alfie Allen (Game of Thrones, John Wick) with a taciturn, almost sulky air. Brett Gelman’s (Stranger Things) take on Terry Nichols is equally baffling, where one never truly gets a sense of their impetus for action. Anthony Carrigan, best known for his brilliant work in Barry as a caustic Chechen gangster with an identity crisis, portrays a highly fictionalized French-Canadian Nazi character without the requisite menace. And Ashley Benson (Mob Land) has the most thankless task of all, appearing as a brief love interest for the consistently disengaged McVeigh, making us wonder what the hell she sees in the first place to be attracted to, completely lacking any cause for empathy when things go as awry as expected.

Perhaps the only performer who truly gets to ride the fine line between menace and sympathy is the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer/actor Tracy Letts. His take on Richard Snell, the murderous racist who was executed on the same day as the bombing, is simultaneously compelling and off-putting. The small-mindedness and delusions of grandeur far more menacing out of the mouth of this incarcerated individual who, unlike with Allen’s portrayal of the titular character, at least occasionally voices his poisonous rhetoric to underscore the terrible actions that resulted in his execution.

An Awkward Aloofness Makes ‘McVeigh’ More Dull Than Chilling

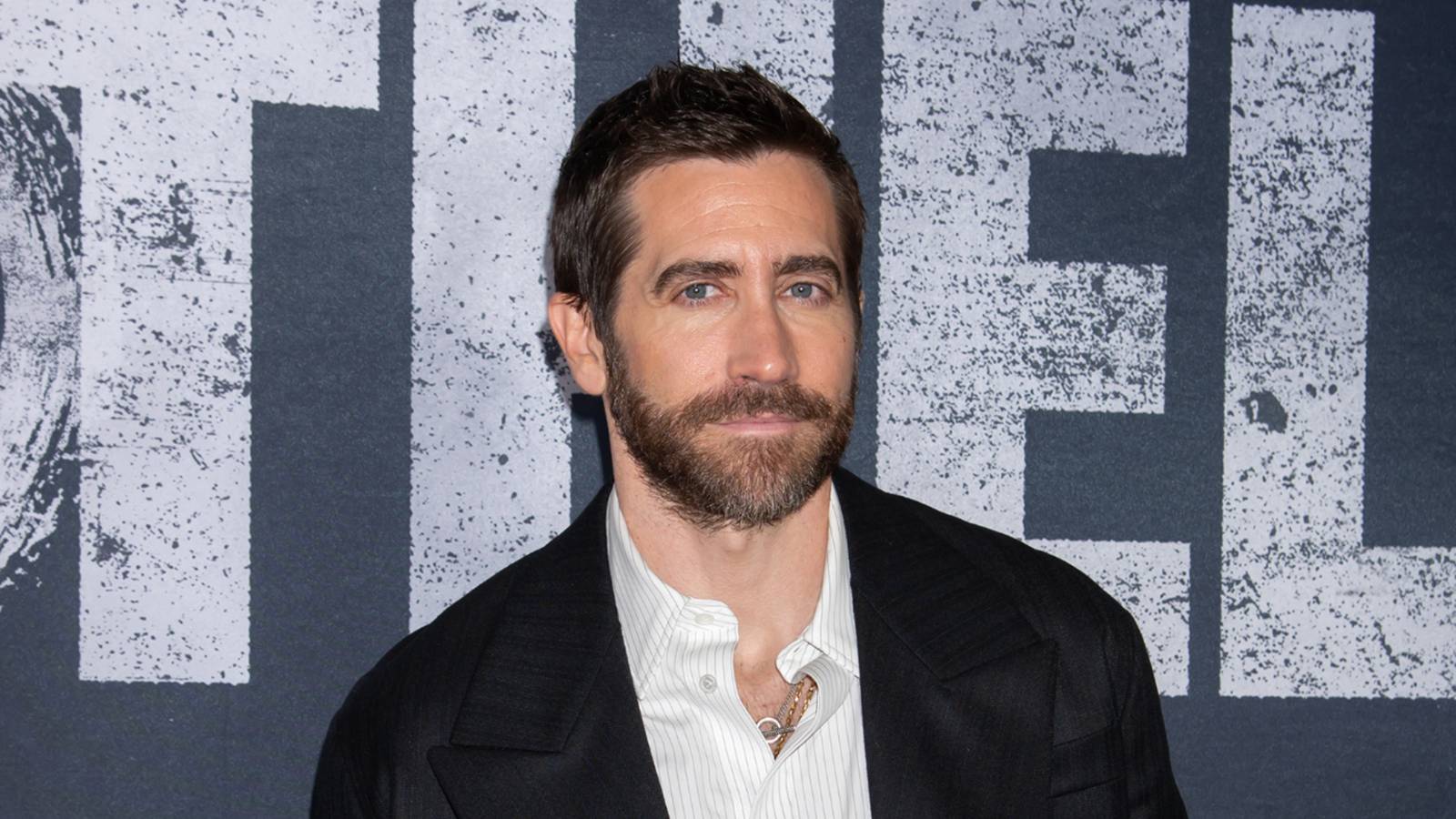

Image via Decal

Ott photographs the aloof protagonist with numerous shots of the rear of vehicles. McVeigh is constantly looking backward from the driver’s mirror, an overt echo to a far superior rumination on sociopathy. Unlike with Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, where there are obvious allusions to Travis Bickle’s rage (and, coincidentally, DeNiro’s character in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil mirrors McVeigh’s use of “Tuttle” as one of his aliases), the low energy brooding makes for a more aimless sentiment rather than a sense of dread. The result is more ponderous than anything, the slow burn means to simmer but instead fizzles out constantly.

When things do try to rise to dramatic effect, we’re left as disengaged as McVeigh’s characterization. The hookup with a barmaid goes basically nowhere, as does a sleepover with some Nazi colleagues that he connects with via a visitor at McVeigh’s gun show booth. What’s stripped away is any sense of ideological fervor, instead presenting a sulky, almost petulant McVeigh who feels slighted by the Clinton administration’s actions regarding the Branch Davidian situation, yet gives off the air of someone on the verge of falling asleep at a moment’s notice.

And so, to answer the initial question above, do we need this film to exist? Cinema, as has literature, art, and even poetry, has been enriched for millennia through a look into the heart of darkness, so there’s nothing fundamentally wrong about engaging with just about any character and their motivations, provided something interesting is being said. Far from being shocking, or an affront to the memories of those who were killed, or aggrandizing the ideas of such pathetic lunatics holding onto their vile prognostications, McVeigh suffers from the more prosaic cinematic crime of being excruciatingly dull.

Is ‘McVeigh’s Problem the Subject, or the Execution?

Image via Decal

There’s nothing here to be gleaned from the watching, no greater insight into the events themselves or the men that perpetuated them. The portrayal of McVeigh as bored and disengaged mirrors the feelings of the audience watching, but not in ways that are seemingly intentional. The coy placement of conspiratorial breadcrumbs is all the more tedious, especially with secreted payphone calls and an apparent John Doe accomplice in the final moments before the explosion that the camera assiduously avoids tracking over to view. It’s tiresome by the end, as if the film is dancing around just how insidious the ideology of McVeigh and his fellow acolytes has become all these decades later, refusing to offend those who have taken up the cause of these psychotic murders under the guise of making their country “great again.”

And so, McVeigh is the least explosive telling of events leading up to one of the largest explosions in American history, an act of war perpetrated by a character that for many embodies the heart of the country’s identity. This brooding, banal, forgettable film is not only an injustice to the gravity of the events it wishes to retell, it’s an outright failure in how it attempts to interrogate the feelings and motivations of these disturbed yet deadly individuals.

There’s a fascinating movie to be made about this period and these characters, but Ott’s telling is simply not up to the task. While a fine ensemble of actors are doing their best to mine the best of what they have been tasked with performing, as a film, McVeigh collapses in ways more pathetic than laughable, a disaster of epic proportions that wraps itself in the horrors of those events thirty years ago without any earned sense of tact or propriety.

McVeigh

Mike Ott’s slow burn take on the days leading up to a mass murder terrorist fails to live up to its subject matter

Release Date

March 21, 2025

Pros & Cons

Decent performance from Tracy Letts, and an ensemble doing their best to make sense of the unknowable.

Dull and dreary.

Provides little in the way of context or truly taking on the more dark elements of the tale/

Overwhelmed by its dour pace and meandering telling/

Publisher: Source link

The SpongeBob Movie: Search for SquarePants Review

It raised more than a few eyebrows when The SpongeBob Movie: Search for SquarePants was selected as a closing night film at AFI Fest. It made more sense within the screening’s first few minutes. Not because of the film itself, but the…

Feb 5, 2026

28 Years Later: The Bone Temple Review: An Evolving Chaos

Although Danny Boyle started this franchise, director Nia DaCosta steps up to the plate to helm 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, and the results are glorious. This is a bold, unsettling, and unexpectedly thoughtful continuation of one of modern…

Feb 5, 2026

Olivia Wilde’s Foursome Is an Expertly Crafted, Bitingly Hilarious Game of Marital Jenga

If you've lived in any city, anywhere, you've probably had the experience of hearing your neighbors have sex. Depending on how secure you are in your own relationship, you may end up wondering if you've ever had an orgasm quite…

Feb 3, 2026

Will Poulter Is Sensational In An Addiction Drama That Avoids Sensationalizing [Sundance]

Despite all the movies made about addiction, the topic does not naturally lend itself to tidy cinematic narratives. (At least, when portrayed accurately.) While actors often visualize the condition of substance dependency through expressive physical outbursts, the reality of recovery…

Feb 3, 2026