Now Showing: Black Panther – Wakanda Forever, Triangle of Sadness, Notre Dame On Fire, The Survivor and The Worst Person in the World

Dec 13, 2022

What’s in theatres? We’ll tell you.

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

Following the death of the Black Panther, Queen Ramonda (a thunderous Angela Basset) and princess Shuri (Letitia Wright) must contend with an international community under the assumption that Wakanda and its all-important Vibranium ore, are vulnerable to a pilfering in the wake of their figurehead guardian’s death. As Shuri’s resentment towards the outside grows, a new aquatic world power makes itself known when Namor (a menacing and persuasive Tenoch Huerta Mejía), king of Talokan, surfaces with an ultimatum: join his people in pre-emptively conquering the surface or become the first to bend to their subjugation.

The first priority: As a memorial to Chadwick Boseman, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever reads as heartfelt, even as certain brand-related intrusions threaten the sincerity of the cast and filmmakers (if you’re going to respectfully delay the Marvel Studios logo, why have it at all? Not to mention a maudlin mid-credits scene). The second priority: As a follow-up to an undeniable cultural event, also from Ryan Coogler, Wakanda Forever falls short of its predecessor, delivering both a fair helping of blockbuster bona fides and missteps.

It helps that there’s just no way to keep a cast this good down. Working with significant gravitas, Angela Basset takes advantage of several explosive monologues, Winston Duke remains impeccably judged as M’Baku, while Danai Gurira’s Okoye is reduced to thankless comic relief for a disproportionate amount of screentime, undermining her character’s resolution. As for Letitia Wright, though she does a commendable job of quite unexpectedly taking over as lead, I find hanging a franchise on her might be a tough ask, and Shuri as a character requires some room to grow.

The best aspects of Wakanda Forever involve Coogler’s exploration of scenes and locations beyond the typical, and when the film makes genuine pleas to emotion, which will undoubtedly go over well with most of the viewing audience being as attached to both Boseman and the first film as they are. A sombre opening and intimate conclusion hit home where the plot slips past, that is, when it isn’t faltering.

The most pervasive issue is the film’s struggle to merge what we can assume were the sequel’s predetermined plot elements and much of its thematic content with the newly prioritized theme at its core: that being Shuri’s difficulty in placing, processing and refusing to redirect the trauma of her brother’s death. Folding this broadly tragic event into her and Namor’s squabble and disdain for the world is unconvincing.

Other issues come down to the nitty-gritty but become sort of inescapable. As we move further away from the opening, Marvelisms begin to rear their head and it starts to feel as though the film is losing its way; especially in the humour which is particularly invasive and flat this time (especially that surrounding new addition Riri Williams, who is at a total emotional remove from the story, and whose introduction ahead of spinoff series Ironheart has been completely fumbled, despite the potential of Dominique Thorne). The CG has not improved much since the weightless Playstation-esque showdown of the first film (maybe the effects community is spread a little thin between all the Disney projects), a flaw pervading a number of the film’s fight sequences (a few of which aren’t up to snuff, none of which are especially exciting). The climax suffers the most, despite being better staged than some of the earlier sequences, but, for all its intercutting of threads, each more desperate to entertain than the last, it can’t stave off the feeling we’ve broached an anti-climax.

This is not particularly significant, but very rarely do technological inconsistencies in these films present a significant hurdle to investment, but they did here. Fantasy technology doesn’t need to make an ounce of sense, but when a film asks that you involve yourself in the minutia of its technology, the political implications thereof, its abilities and shortcomings, then it’s begging to be scrutinized. Why, for instance, can characters be sky-beam airlifted out of the ocean in one scene, but we are expected to worry for a gaggle of heroes who’ve tumbled into the ocean, where they are at a disadvantage, 15 minutes later? Does the most powerful and technologically advanced nation on earth have no better way of battling an aquatic army than pitching up in a boat? And why is there only one such boat? If it were a matter of staging an honourable battle that would be one thing, but for the sake of a vendetta, as it is here, why not drop the Vibranium equivalent of an atom bomb on Namor’s forces, ready the batter and vinegar and call it a day? But, these are not important issues.

These days when Marvel produces a less than functional project, something has gone very wrong in the manufacturing process. That’s not the case here, everything is in its right place, and will, for the time being, serve its purpose. Wakanda Forever is remarkably uneven, and though the film satisfies the immediate needs of its audience, it will more than likely in time reveal itself to be weaker than it once seemed.

Triangle of Sadness

First, an argument. Then, a luxury cruise gone very wrong, several times over. Then, a deserted island. Triangle of Sadness follows the wealthy-and-or-beautiful through a series of increasingly debased circumstances. What fun.

There have been some complaints in the critical sphere since Triangle of Sadness took home the Palme D’or, that it takes aim at easy-targets with a shotgun blast of satire lacking in complexity. This is missing the forest for the trees. Triangle of Sadness is an outrageous comedy of social errors with a knack for highlighting our predilection to be petty (emboldened by status, monetary or otherwise). First and foremost, it makes for great, raucous entertainment. Director Ruben Ostlund’s films are made with a mind to prod, not to dissect (what’s the saying about jokes and frogs?).

That said, it’s not as if Triangle of Sadness is bereft of sociological interest, and anyone with a passing familiarity with the ultra-wealthy will recognise that there is little in the way of exaggeration here. If you peel the movie apart for deft psychological profiling and a precise untangling of the strife between socio-economic strata, it may not entirely satisfy your demands, but for something as funny as this, it is far sharper than it needs to be.

All this would be for nought if the film’s cast weren’t up to the task of its high-wire balancing act between the skin-crawlingly familiar and the extremes developed on the edge of dignity. The cast is pitch perfect, from the likes of the broad work of Zlatko Buric and Woody Harrelson, acting out an ‘intellectual’ duel between a Falstaffian Russian oligarch and a self-loathing socialist ship captain, to the restrained Charlbi Dean, her last role betraying a subtlety of great promise.

The vestigial remnants of the theatrical-released comedy have been less than satisfying lately, and it was refreshing to sit in on one that wasn’t only partially interrupted by perfunctory chuckles of recognition (if it walks like a joke, it would be impolite not to snort), but one where for long stretches gasps rolled into full on cackles. Of this week’s slate, this is the film you’ll have the best time with, provided your flavour of choice lands somewhere between the crude, the restrained, the cringe-inducing and the prickly. Note: if you don’t take well to lengthy vomit/scatological scenes, maybe bring a good book along to keep busy for that portion of the film. Not ‘Love in the Time of Cholera’.

Notre Dame On Fire

Notre Dame On Fire (it’s original French title, delightfully, is Notre Dame Brule) is exactly what it says on the tin, no frills, no histrionics; a moment-by-moment reconstruction of the 2019 blaze, the rescue of its key artifacts, and the men and women who put their lives on the line so that it might stand. Through this clear-cut approach, Notre Dame On Fire avoids becoming what, considering its sensational subject and international appeal, it had every chance of becoming. That being the worst sort of French film: an American French film.

Director Jean-Jacques Annaud, gifted as ever, emphasizes the strain involved in these efforts, shooting for absolute realism, going so far as to incorporate archival footage of the disastrous fire into the edit. The logistics involved, given rare insight for a non-documentary disaster film, keep your interest, and a well-realised ensemble of Parisian citizens and key-players duly fulfil their muted roles.

Precisely how involving an audience member will find this take will depend entirely on their expectations and requirements of a film about this event. If you want a well-realised, play-it-straight-drama with total fidelity to the play-by-play of the fire and rescue operations, where the most remarked on stakes concern religious and historical heritage, this is that film. If you are looking for a more conventionally written, familiar, Hollywood approach, with a focus on characters, personal stakes, arcs, a rising action, etc., these aspects are downplayed. A telling moment: partway through the film, we cut away from the fire to an unaware senior citizen in a panic; her cat has strayed onto the slanted roof nearby and needs rescuing. Then, it slips, landing precariously atop a loft window. This moment produced the strongest reaction of the entire screening (audible gasps all around). Annaud’s impersonal approach is admirable, but for much of the film the results are dramatically inert.

The saving grace of Notre Dame On Fire is its recreation of the inferno as we’ve never seen or heard it. Being so familiar with the sight of an event, only to have the experience of it recontextualised (especially through sound); there is a constant awareness of the texture of things; narrowly avoiding the heavy splash of molten lead or disappearing into a sound dampening cloud of smoke, a rising heartbeat your only companion. Thankfully, Annaud has no trouble in making us feel present.

Notre Dame On Fire doesn’t burn the house down, but shouldn’t disappoint either.

The Survivor

Based on the memories of Hertzko ‘Harry’ Haft, dubbed the ‘Survivor of Auchwitz’ during his brief post-war boxing career. Haft, interned in concentration camps for the duration of the war, was trained to box by an SS officer and forced to fight fellow prisoners to the death for the entertainment of the officers. This period is seen in black and white flashback; the memories and guilt are inescapable for Harry, knowing his survival came at the cost of others, and now a light heavyweight boxer determined to face off against rising star Rocky Marciano. Heft is convinced his first love has survived the war, and that news of a high profile fight might reach her. The Survivor is not much of a sports movie, though smatterings creep in, it is more of a character piece. Heft’s experience is very nearly totally unique, and yet all too applicable for many who suffered through history’s greatest failing, and that is worth recalling.

The Survivor sometimes succumbs to overly conventional handling (though nothing in the film is left particularly neatly), for instance: there are images of such extraordinary power at play during Heft’s matches that musical accompaniment (however slight composer Hans Zimmer’s treatment may be) seems a moot point. This story doesn’t require the little Hollywood tidy-work involved, but finds ways to escape it’s bounds nonetheless.

For one, there is no shying away from suffering, internal or otherwise. Haft is fascinating and Ben Foster’s central performance is enthralling. It’s not uncommon that an actor in character be unrecognisable from their red carpet ready self, but here Foster as a young Haft at Jaworzno is hardly recognisable as the battered fighter we meet in post-war New York, and still less so as the middle-aged greengrocer letting his pain bleed to those around him. Foster’s performance is unflattering, unwavering and so thoroughly unaffected it’s bound to be overlooked.

Not to say that the rest of the cast, Vicky Krieps, Billy Magnussen, Peter Sarsgaard, John Leguizamo, and Danny DeVito among them, aren’t on point. Each plays their part, as the film itself does, precisely, with that unique old-Hollywood sophistication, mostly sidestepping that unique old-Hollywood sentimentality. The results are affecting and should not be overlooked simply because The Survivor has come up short on awards buzz this year.

The Worst Person in the World

Julie is nearing 30, and can’t decide what she wants to do, or what she wants from her love life. Or more accurately, she’s very good at deciding, and then changing her mind. She’s a medical student, then a psych major, before settling on photography. Maybe writing too. If we go by what she does during all this, she’s a bookstore attendant. She sleeps with one of her portrait subjects, before meeting and promptly falling in love with Aksel, a comic book artist a decade her senior, warmer on the idea of having kids than she is. One night, attending a cocktail party with Aksel, she’s so moved by boredom that she takes off and crashes a wedding afterparty.

She and a lonesome but taken attendee spend the night debating and performing whatever forms of intimacy don’t constitute cheating. And so on. This premise sounds like it could make for fairly standard romcom fare, but The Worst Person in the World is quietly subversive, fleetingly prone to imaginative flight, and beyond emotionally knowing. It plays as if without fault. And what a soundtrack!

The dexterous script has been lauded time and again since the film’s initial release, probably nabbing attention for its wordy and forthright passages of narration and realistic conversational dialogue, but it’s the reined in sequences later in the film that leave a greater impression and become unexpectedly poignant. The film is justifiably divided into a prologue, 12 chapters and an epilogue, each a complete thought, and none out of place.

An understanding, ultra-modern rom(?)-com(?) about arrested development proceeds to faithfully follow the shape of life in all its unpredictability, and its characters in their truthful and uncontrived complexity. “I feel like a spectator in my own life. Like I’m playing a supporting role in my own life” Julie says during an argument. That’s a good way of saying you have no idea what’s wrong, because you’re not sure what would be right. An argument could be made that our lead isn’t fully realised. Another way of putting it; she’s as tenuous as the story makes clear she is to those around her. Julie is endearingly, frustratingly impulsive, refreshingly unmarred by the principles of typical storytelling bending their protagonists to ideals (true love and whatnot).

Though it never quite reaches transcendent heights, it’s certainly worth catching this 2021 gem in the cinema (now showing at the Labia theatre).

Publisher: Source link

Lamorne Morris Thinks Kamala Harris Has This Advantage Over Donald Trump

Trump said that President Joe Biden, who dropped out of the race on Sunday while recovering from COVID-19, never really had the infection. “Really? Trump thinks Biden never had COVID?” Morris said on Monday. “You don’t pretend to have COVID to get out…

Jul 26, 2024

Khloe Kardashian Is Ranked No. 7 in the World for Aging Slowly

Khloe Kardashian's body is out for more than just revenge. In fact, the 40-year-old is one of the world's slowest agers—a revelation she learned after taking a blood test to determine her body's biological age compared to her calendar age.…

Jul 26, 2024

Reactions To Trump’s Kamala Harris Donation

Just as many white Americans used their Obama vote to excuse their internalized racism, Lauren Boebert seems to have adopted this same ideology, ignoring Trump's long record of racism against African Americans, Mexicans, Hispanics, Native Americans, Muslims, Jews, and immigrants, and discrimination against women and…

Jul 25, 2024

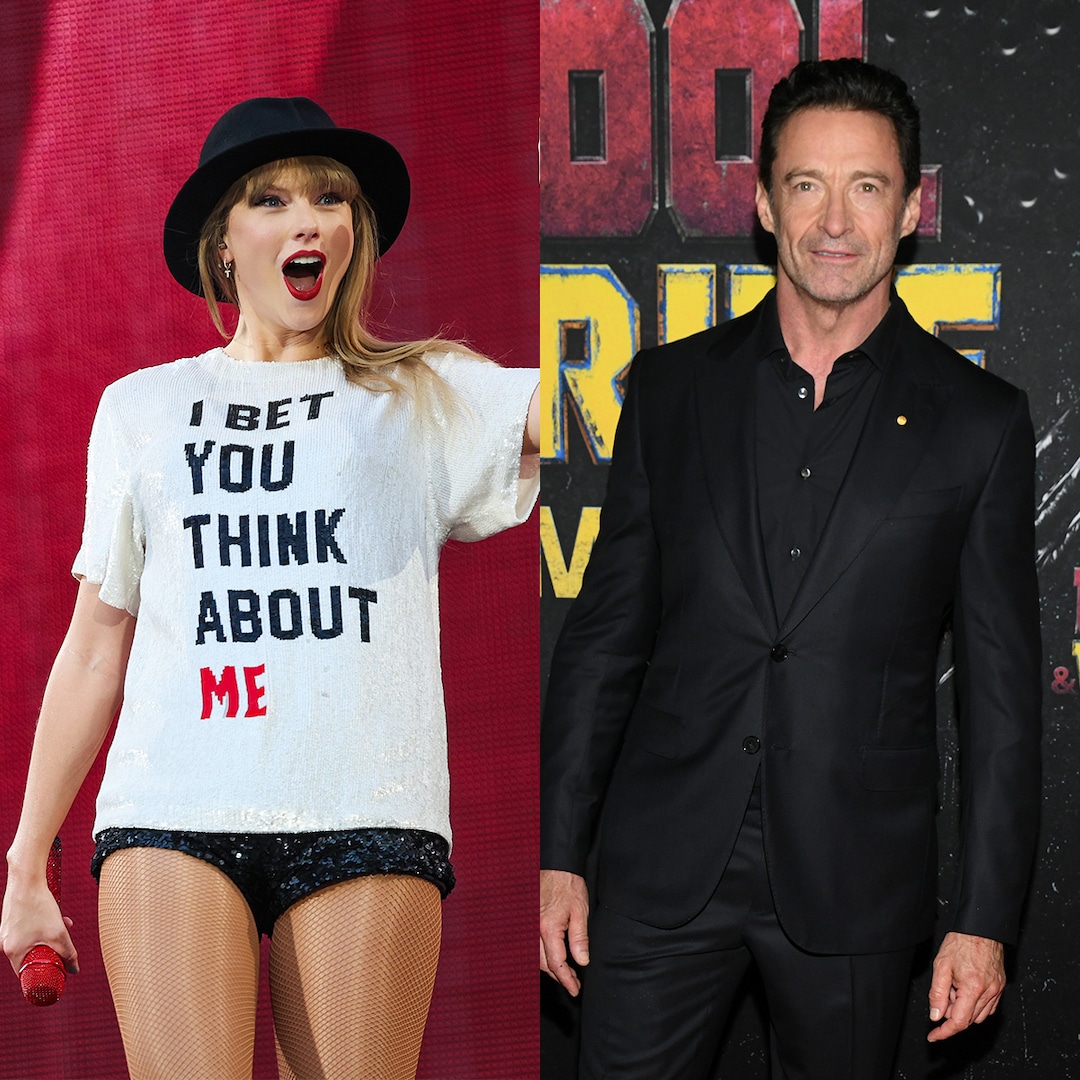

Hugh Jackman Reveals What an NFL Game With Taylor Swift Is Really Like

Hugh Jackman is happy to fill any blank space in Taylor Swift’s NFL game suite. In fact, the Deadpool & Wolverine star recently detailed his experience attending a Kansas City Chiefs game to root on Travis Kelce, alongside Ryan Reynolds,…

Jul 25, 2024