’Oppenheimer’s Ludwig Göransson & Hoyte van Hoytema on Nolan’s Masterpiece

Dec 29, 2023

The Big Picture

The cinematographer and composer of Oppenheimer reflect on the challenges of bringing the film’s complex story to life. The use of the IMAX camera in the film created an intimate and immersive experience for both the audience and actors. Christopher Nolan’s directing style blends precision with intuition, allowing for a unique and immersive filmmaking experience.

Following our very special IMAX screening of Oppenheimer, Collider’s Steve Weintraub hosted a Q&A with cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema and composer Ludwig Göransson to talk about the behind-the-scenes of one of this year’s biggest blockbusters. It’s little wonder why the auteur has worked with them on multiple occasions – both are masters at their crafts.

To celebrate Oppenheimer, Collider was thrilled to give readers an opportunity to see Nolan’s grandiose biopic in the format that was intended one more time. As well as seeing the performances of the stellar cast, including Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, and Emily Blunt, led by Cillian Murphy, the audience got to experience Göransson’s score and Hoytema’s camera work that brought the turmoil of the father of the atom bomb back to life.

Check out the video above or the transcript below to find out what the most difficult elements of Oppenheimer were to capture on film, how Göransson worked with Nolan to create the movie’s sound world, and what it’s actually like to work alongside a director like Nolan. The pair also discuss the real reason Nolan doesn’t use CGI (when he can help it), building sets in one day, how many cameras he uses on set, and tons more.

Oppenheimer The story of American scientist, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and his role in the development of the atomic bomb. Release Date July 21, 2023 Rating R Runtime 181 Main Genre Biography

COLLIDER: When did you both realize, “Wait a minute, this movie is gonna be huge and resonate with so many people?”

LUDWIG GÖRANSSON: I took the whole summer off and I spent the whole summer in Sweden and I went to a small little village. I remember the day before the movie came out, I bought my tickets and that little theater in that little small town was sold out. That’s, I think, when I realized that people were very interested in this movie.

HOYTE VAN HOYTEMA: You didn’t think that could have been because of you?

GÖRANSSON: [Laughs] No, because the day before the screening, I was up in the town, that little village, and my wife Serena [McKinney], she saw some kids in all pink and she was like, “Oh look, they’re gonna go to the Barbie movie.” Then she saw some other guys behind them and they had, like, dark clothes on and were smoking cigarettes, and she was like, “Oh, they’re gonna go to Oppenheimer!” She went up and asked them, “Are you guys gonna see Oppenheimer?” And they didn’t know what she was talking about.

HOYTEMA: I had an interview at nine o’clock in the morning at the Chinese and there was literally people posting outside with fedoras and smoking cigarettes. [Laughs] But to be serious, this film, it was not very obvious that it would get the response that it got. I mean, it’s effectively people talking, and people talking about science, so when it started to get a little traction it was a bit surprising, I think. A very pleasant surprise in many ways. Of course, we did everything to make the story as palatable as we could. Chris always had a very strong faith that this was going to work, and we kind of always followed his lead in this, but it was a very pleasant surprise.

Capturing ‘Oppenheimer’s Complexity in Sight & Sound

A lot of people in this theater know how the sausage is made, they know the behind-the-scenes of making movies, so what were some of the unique challenges you guys faced in bringing this film to us?

HOYTEMA: For me, it’s very much that on a script level already, you’re working with faces and dialogue. On paper, it’s not a very obvious cinematic experience, so I think for me, the biggest challenge was, from the outset and from the start, to create something that has the scope, but also has the dynamics in terms of its visuals, right? Because a close-up, it’s like playing an open chord on the guitar normally when you order a crescendo in a piece of music. It’s like the biggest chord is the close-up, and if you put a lot of them next to each other in a film it can become monotonous and you can lose your dynamics a little bit. So for me, that was very much a challenge to keep faces and keep close-ups interesting and keep them dynamic enough so that you could sit through the movie and go through the different peaks and low points as you would in a normal film.

GÖRANSSON: With the music, I started right after I read the script. The music needs to make the audience feel like you’re in his shoes, you’re seeing the world through his eyes, you’re feeling what he’s feeling and you’re not sitting there judging him. You’re with the character the whole time, with Oppenheimer. So I always knew, after I read the script, that the essence and the most important part is to get the emotional core of the music to really work with his character and all the different states of emotions that he goes through. That was, for me, the most challenging part because he is such an incredibly complex character and he has so many complex feelings and I need to try to go there myself in terms of trying to get that out, and that was difficult at times.

HOYTEMA: “You going there,” meaning you had to learn quantum physics. We all did.

GÖRANSSON: [Laughs] Yeah, we all did. But what was so great about after I read the script is that Chris Nolan was also getting involved very early, so one of the first things I do is he and Hoyte, they’re having test shoots and then they have screenings where you show some of the things that you’re trying out, and I remember early on I went to see one of those screenings that was at the IMAX 70mm theater. I’m sitting there in a theater and I’m seeing this close-up image of Cillian Murphy laying in bed, and I’ve never seen anything like that. It’s such an intimate performance, and intimate in capturing a face like that on such a format. That had a tremendous impact in the way that I was starting to hear the music.

The IMAX camera is so massive. What is it like putting that camera right next to people’s face? Because it’s different than a normal camera and I’m wondering how it affects people?

HOYTEMA: Well, it’s not necessarily massive – it’s loud. It’s like having a small little diesel engine in the shape of a small mini bar on the shoulder. For actors I can only imagine how intimidating it must be, but you have to kind of learn to switch yourself off, I suppose. It’s very, very intimidating, and of course, Chris and I decided that we wanted to be closer, we wanted to be more intimate with that camera than we had done before, which makes it even a little worse. But I just have to say all kudos to the actors that somehow understood the subtlety that a camera like that can pick up and could sort of do whatever they do in spite of the noise and the proximity of that beastly machine. And it’s not only the sound of the camera is here but it’s also my weird face very close in the viewfinder. [Laughs] But Chris is very good at explaining the premises of what we’re doing to the actors. Everybody knows what it means to shoot on a big format like that, not only work-wise on set, but also the implications it has when you project it and what do you see and so on, and somehow everybody is very much in on that game from the start, from the outset.

I read that Chris gave you the hint of a violin, or he said something about he heard a violin, so talk a little bit about what it’s like having a director give you that sort of guidance. Is it something that you enjoy or is it something that messes with you a little bit?

GÖRANSSON: It’s definitely something I enjoy. That was the first thing that he said after I read the script, he’s like, “I don’t have that much to give you right now, but I have an interest in seeing what we can do with having the violin channel Oppenheimer and his personality,” and I thought it was very interesting. I was asking why and he was explaining that the violin, with it being a fretless string instrument, you can go from this super romantic, beautiful sound to something neurotic, and basically just on the vibrato of the violin, just within a split second, going between those feelings. I thought it was a great start, and also, my wife Serena is a violinist so we spent endless hours in the beginning just trying to come up with different techniques and also different ways of using strings to channel feelings. Traditionally in the theater and when you see movies, the way strings are used in horror movies, for example, it’s like these big clusters. Everyone knows the Psycho strings, or these “horror” violin string clusters, but what if you take these clusters and instead of playing them with a very, very intense neurotic tone, you make it beautifully broader instead? What feelings is that gonna make?

Christopher Nolan’s Directing Style Is a Strange Hybrid

Image via Universal Pictures

Everyone in here is a fan of Christopher Nolan. What do you think might surprise fans of Christopher Nolan to learn about working with Christopher Nolan?

HOYTEMA: What I love with Chris, which is not always obvious, is that his films always appear to have a very high degree of precision, but when I work with him I feel that I work with a person that is not afraid whatsoever to work in a very intuitive way. He has a very good sense of things that are going on on set. He always has a very broad idea about what he wants to do, but when random things get fired at him, he always knows very well how to adapt. He’s somebody that is not afraid to go with the flow in spite of the precision of the work itself. I think that very often people don’t see him very much as somebody that can be very intuitive, and that very oftenly mistakenly [think] he’s so much about precision and planning, but he’s this kind of very strange hybrid in between that. Then you read the script afterwards again after the film is on the screen and you realize everything is kind of written in it, and then again this precision comes back, but on set, and I think the actors feel very much the same, he’s very open and very reactive and responsive and in intuitive.

GÖRANSSON: Also, something that I think is incredibly interesting, especially, is his curiosity. Especially when I’m in the middle of writing some kind of music and I’m using some kind of composing technique or any kind of computer technique, he’s so keen on understanding what it is and learning it, and really getting into depth of the craft. I know that he’s like that on every level, not just music, but in every different craft, and you can tell in the movies, obviously.

HOYTEMA: Yeah, or he comes back the next day and then has seriously read up on it and knows more about it than anybody else. Like with music, the same goes with the technology around it – optics, camera technology, lab technologies, light. He always tries to know a lot about everything, and I always have the feeling that that sort of amounts in you trying to better yourself, as well, and into results that are always kind of interesting.

GÖRANSSON: Absolutely, and I’m talking about music but also talking about sound. The amount of detail that he puts into the sound mix, into the dub station, the knowledge of the subs and the speakers and all that.

I have an individual question for you. How do you know, as an artist, when your piece of music is done? Is it like an instinctual feeling or do you tend to go back to something even when you think it’s done, just sort of tweak it a little bit?

GÖRANSSON: I try to tweak it a lot of times. I mean, the only reason that I know that it’s done is because we’re running out of time. Also, with Chris we sit literally through the last day of the dub with the music. There was one cue that took forever to finish and we finished it before the last day that we had to wrap the entire movie. Also with Chris we know when it’s perfect. I know when the music is done, I know when a cue is done, but I’m always trying to push it as much as I can and perfect it until the time is over.

HOYTEMA: Well, but there’s a beauty to things that are not entirely done, as well. For instance, it’s always nice to sort of incorporate and not engineer things to death and sort of at some point just accept, “This is what it’s going to be and this is what it has to be.”

GÖRANSSON: That’s one of the hard things.

HOYTEAM: It’s hard, but I think it’s like shooting stunts, for instance, on set. Sometimes those stunts, they’re not perfect, but then you’re sort of weighing every time you put somebody through a stunt it’s always a little bit dangerous. It wasn’t perfect, it wasn’t the way you had it in your head, but the way it happened it was kind of good, as well, and maybe we should just stand on it and let this be exactly the way it is and move away and move on. I think there’s some sort of a craft to that as well.

GÖRANSSON: Absolutely. Having that understanding is very difficult.

This Is Really Why Christopher Nolan Doesn’t Use CGI

Image via Universal Studios

One of the things that people might not realize, or maybe they’ve heard about it, is that this film has no CGI and you have some incredible visuals in this that are being done practically. Can you talk about making a film like this with no CGI and trying to photograph what he wants photographed using IMAX cameras or 65 millimeter cameras?

HOYTEMA: There’s, of course, a distinction between CGI and visual effects. There’s more than enough visual effects, but every effect in the film is based or derived from something that is shot tangibly. So every element you see is, at some point, committed to camera, and there are some shots that are built up from several elements, for instance. But we always try to do things as much in camera as possible, and very often people think that we do that out of some sort of vanity, but the truth is we try to do it in camera as much as possible because every time we do an effect in camera we don’t have to scan it, which means we can maintain the full 18K resolution that an IMAX negative can have. The moment you start scanning it, you already throw away half of the image quality that an IMAX can capture. So, the fact that we do things in camera has a very clear purpose for us, and that is we want to maintain as much as possible quality in the original negative.

I’ll just say, and I think the audience will also agree, that when I see things that are just visual effects with a lot of green screen or lighting behind it just looks fake to me. I think the way you guys shoot your movies, one of the reasons it feels so real is because of the practical nature and the analog nature of what you’re doing.

HOYTEMA: Yeah, because it is very often not fake. I think it’s just very hard to conceive a lot of things from the luxury of a glass cubicle, and literally, when you do CGI every single element in a shot, including the highlight and the kick and the weird vibration that the table is doing, you have to invent that and you have to make that up, and somehow the human mind cannot compete with what nature gives us naturally on a way to do it. So for me, it’s always very obvious that you try to do things for real if you want things to be real, and whatever you can’t do, you work very hard to invent a way so you can. If then you fall short, then you maybe resort to CGI. It’s, of course, very dependent on what kind of films you do, but I think this film lended itself very, very well to trying to do things practically. All these kinds of things we were doing were sort of science projects in itself, and so doing that, you also learn a little bit and you also have to invent a little bit of things here and there and you see what works and what doesn’t work. Slowly you kind of study yourself forward through that complexity. Instead of just conceiving of something you wanna see and then putting a vision on the screen, it’s much more something that is slowly cobbled together and comes a little bit from curiosity and wanting to learn.

In terms of writing the music, how much do you need to see the footage before you’re really writing a lot? How much can you write to the script, how much can you write to those first test shots, and how much is it like, “I need to see the movie?”

GÖRANSSON: So I think your biggest enemy on any of this is just time, so the more time you have to do anything and the more time you have to write music, the better. Normally when you finish shooting a film, you go into post production, you make an edit, and then you have three or four months before the movie’s done, before you have to finish the movie, so that’s why it’s so crucial to get started early. That’s really, I think, what’s so unique is that we have a lot of time. When Chris is in pre-production, two or three months before he starts shooting the film, we meet up once every other week or once a week and I write music every week based on the script, based on our meetings. Then we sit down together, we’ll listen to it, we talk about some details, we talk about what characters they could work for, what sounds we like, so when you guys take off shooting, he has about two or three hours of music that he listens to on set, and then sometimes he calls me from set and has notes. “Turns out this is looking a little different now, what if we do this?” And when he starts putting his first edit together with Jennifer Lame, the editor, they don’t use any temp music.

Temp music is something that is used almost in every film. When you make a first cut, you put in music from already existing films, but what we do here, with Chris, is that we put in music from the two or three hours of material that I’ve already written. So immediately from the jump, when you see the first cut of the film, you have a whole unique sound world and music world, something that’s crafted and put together just for this emotion, for this feeling, for this movie. Then, my job really starts. We have a lot of music already in the movie, but now it’s time to really craft through the scenes and get the material that wasn’t written. Also, for this movie with this length there’s a lot of music that needs to come into place, so for the last four or five months of this process, after we have a first cut, it’s pretty much a heavy-duty job to get the music in place.

And then also, obviously, the last thing that we do on this project is to record it all with the live orchestra — especially with this film, which I would say 80% of the music is played by a live string orchestra — and just listening and seeing how much of the music ends up changing based on the live players, just the dynamic. Really getting that human touch and the human element into the music really changed it a lot because we would really be able to play out the dynamics. I feel like in music and most art and most theaters whenever you’re exposed to music or listen to radio, everything is always compressed to maximum level, just from cranking it up. I think with this film’s sound overall, but also with the music, something we were trying to do was just really create something dynamic.

HOYTEMA: I also love the fact that you turn up so often when we watch dailies because we actually all watch dailies together. So during the shooting you’re very often there. In a way you getting a little taste of the set.

GÖRANSSON: Yeah, you watch dailies every day and I try to come in there even though it’s no sound, but just getting some visuals and seeing the incredible footage that Hoyte has been getting is very inspiring.

Also, I’m sure it’s an education in terms of learning filmmaking in case down the road you ever decided you wanted to direct? This is like the best film class ever.

HOYTEMA: Why would you do that? [Laughs]

GÖRANSSON: Yeah, I remember I went to set one day and I saw they were shooting that scene in the beginning when Robbie and Oppenheimer are in that little train and they’re having a conversation. And that was tiny, that little train, and then you were standing, I think you were poking in a window with your camera — it’s a huge camera — and then they built this little train cabin out of wood and Chris was jumping on the stage to make it shake. [Laughs]

HOYTEMA: As well, it was not in a studio, but we happened to shoot at a location here downtown that happened to have a room, and schedule-wise we had to do it that day, so we literally built that train set that was driving to Zurich in a room somewhere with Chris jumping up and shaking it.

How Many Cameras Does Christopher Nolan Work With?

Image via Universal Pictures

Roger Deakins shoots famously with one camera and Ridley Scott likes to shoot with six or eight cameras. I’m curious, what is it like on set for you guys? How often are you using one camera? How often are you shooting things with multiple cameras?

HOYTEMA: It’s safe to say that we are, with a few exceptions of dangerous stunts or visual effects, we are a one-camera show. So, we work with one camera and one camera only. We try to be meticulous with what we should, as well, in a very old-fashioned way you could say, but we work with an analog camera that has an optical viewfinder, so whatever gets into that camera, you look through it through an optical viewfinder, and it has a very bad video assist, so Chris is usually resting next to the camera looking from the vantage point of the camera onto the set. So everything that happens in front of the camera, it’s all built around that sort of funnel that goes into that one single lens, and I think we both love working like that. So, we’re definitely a one-camera show. And by the way, to have two IMAX cameras next to each other noising it up… [Laughs]

Well, hopefully there will be a smaller camera soon.

HOYTEMA: I’m not sure if I agree because there’s something very magical with the fact that you have a set and you plant something in the middle and all the life and the chemistry on set sort of starts evolving around that thing that is standing central there. It’s a certain respect and all that people are around it, and they start sort of living their lives and building their things all around that gigantic vacuum cleaner there in the middle that is then supposed to suck everything up. So I think the size is not a problem. And then the other part of it is that I always feel it as my obligation as a cinematographer to kind of master the technology and the discomfort in order to get the best experience possible, so I’m not so much into ergonomic or more handy solutions that make it easier for me to pick up or anything like that. I think it’s good that there’s a little resistance, and that always kind of works to my advantage.

By the way, the IMAX camera, we all talk about it like that’s the heavy camera, but the System 65 camera, the 5G camera, is much heavier and much harder, in a way, to work with. Besides that it pulls 65 millimeter strips of film through its mechanics, it also is built in a case that is thick and heavy in order to not let any sound out. So, the IMAX camera feels like a very ergonomic and easy thing to work with compared to the System 65.

I have never heard anyone say that the IMAX camera is ergonomic and easy to work with.

HOYTEMA: No, it’s really not that bad. There are all these myths about it. When I started working for the first time on IMAX, everybody was saying, “Ooh, the IMAX camera…” and when I stepped into it, I thought it was like a Volkswagen Beetle or something, that big, and people say, “Handheld is impossible.” And then at some point you go to the rental company, you see the thing, you think, “No, it’s not that bad,” and then you pick it up and it’s not that heavy, actually. Then you ask somebody to put it on your shoulder, and just by doing that you find out the stories or the mythology around it weighs so much more than the camera itself.

Oppenheimer is available to rent or purchase on Prime Video and you can look forward to the film’s upcoming IMAX 70mm re-release.

Watch on Prime Video

Publisher: Source link

11 Famous People Who've Reacted To, Been Embarrassed By, Or Absolutely Loathe The Memes That Have Been Created About Them

Dua Lipa said the "Go girl give us nothing" meme was "humiliating" and "hurtful." She had to take herself off Twitter because of it.View Entire Post › Disclaimer: This story is auto-aggregated by a computer program and has not been…

May 19, 2024

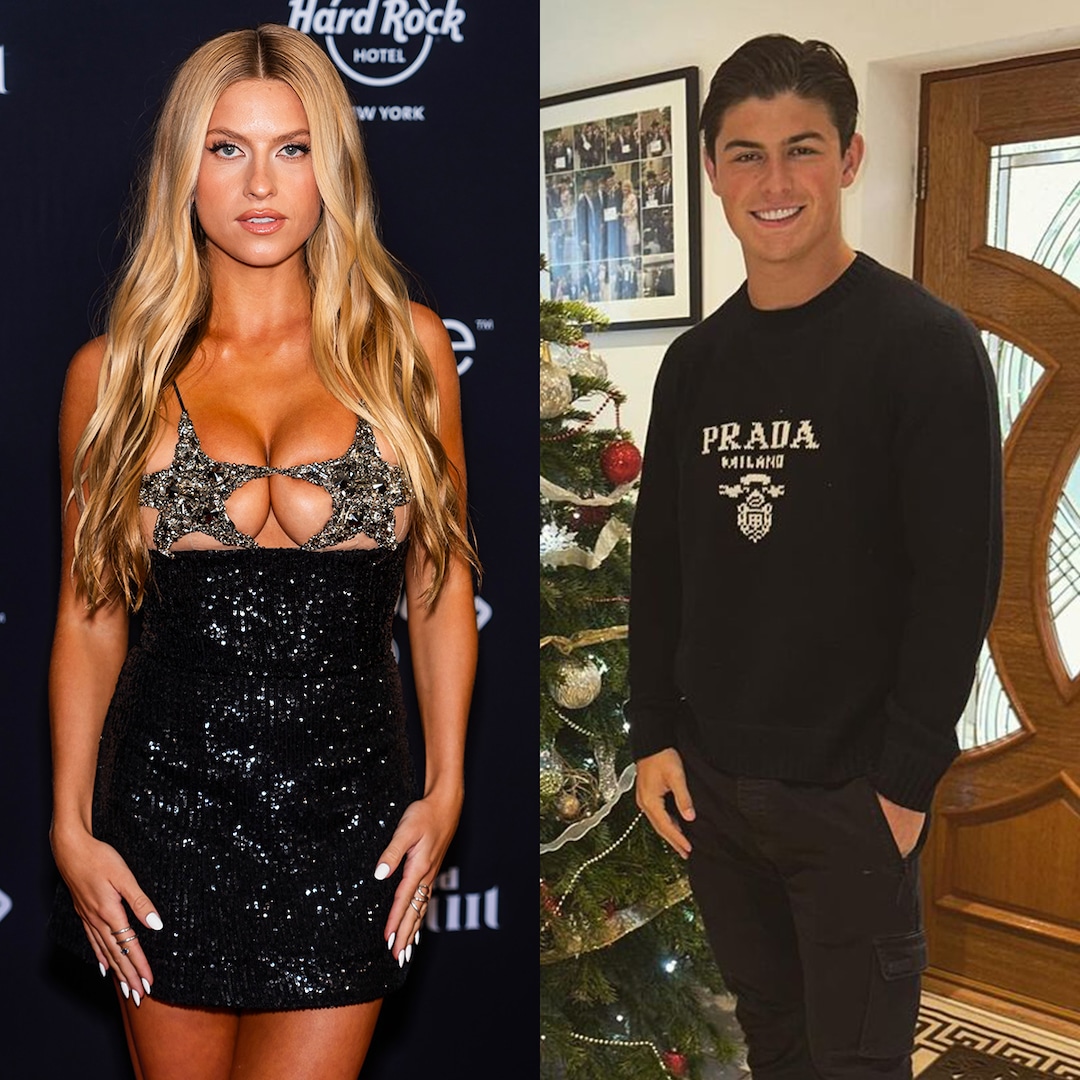

Is Xandra Pohl Dating Kansas City Chiefs’ Louis Rees-Zamm? She Says…

Did Xandra Pohl find her own guy on the Chiefs? The TikToker sparked romance rumors when she and Kansas City Chiefs player Louis Rees-Zamm were recently spotted at the Worlds of Fun amusement park together. Though the pair looked quite friendly in Instagram…

May 19, 2024

Kelly Clarkson Discussed Weight Loss And Ozempic Rumors

Kelly Clarkson Discussed Weight Loss And Ozempic Rumors A few weeks later, Kelly discussed her physical transformation for a second time, celebrating the fact that she no longer felt the need to wear shapewear. Amid all the speculation, Kelly attributed…

May 18, 2024

Early Memorial Day Sales You Can Shop Now: J.Crew, Spanx & More

Kate Spade: Save 40% on Kate Spade markdowns. Kate Spade Outlet: Nab 70% off hundreds of Kate Spade styles. Plus, an EXTRA 20% off shoes and crossbodies. Lilly Pulitzer: Shop 25% off deals on Lilly Pulitzer spring styles. lululemon: Technically, there isn't a lululemon sale…

May 18, 2024