“The Algorithm of It All”: Tucker Bennett and Chris Corrente on “In the Glow of Darkness”

Oct 27, 2025

In the Glow of Darkness

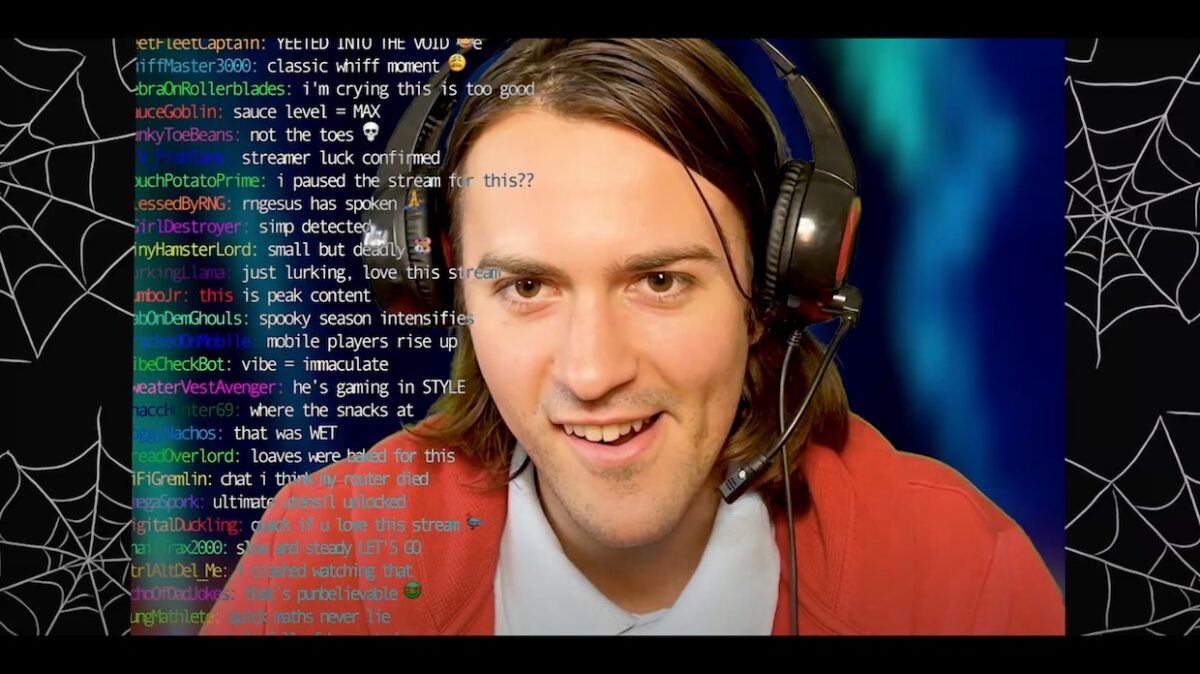

Drawing heavily from internet aesthetics that feel at once contemporary and dated, In the Glow of Darkness is a sprawling, hand-made cyberpunk ensemble film following detectives, streamers, pop stars, struggling families, corporate conspiracies and a rave-dancing hitman. Eschewing direct references to our world’s online space, In the Glow of Darkness constructs a parallel reality of tech-run nightclubs, LAN party fraternities and a “meme-tripping” drug culture, where users get have their subconscious uploaded to a QR-code tramp stamp, which, when scanned, gives them euphoric hallucinations as well as sending AI-generated targeted ads directly to their brains.

Tucker Bennett started making films at San Francisco Art Institute, where he and close collaborators Chris Corrente (who scored In the Glow of Darkness and Bennett’s previous film, Planet Heaven) and Zach Shipko studied under the late, great pioneer of American underground cinema George Kuchar. While at SFAI, Bennett co-directed the VHS-shot Why Are You Weird?, an awkward undergraduate dating comedy that the pair released for free in 10-minute increments on YouTube embedded onto the web art collective site JstChillin. Bennett would go on to make two more DIY films in the 2010s, Bloodrape and Candelabra, before he started working as an editor for Eugene Kotlyarenko on We Are and The Code.Riding the momentum he had after 2022’s Planet Heaven—an update of Bennett and Shipko’s characters from Why Are You Weird? which finds the pair at the Los Angelino intersection of tech and wellness by peddling a chakra app—In the Glow of Darkness is Bennett’s fifth feature and best work yet.

I had a long chat with Bennett and Corrente over Zoom after In the Glow of Darkness played at New/Next Film Festival. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Filmmaker: To start off, can you tell me about how you two started working together?

Bennett: We met at San Francisco Art Institute. When I came into school, I wanted to shoot on black & white 16mm and make art films about loneliness—people looking out the window and dirty dishes, little apartment stuff. We’re both students of George Kuchar and true disciples—there’s kind of a before- and after-point for both of us between meeting him and him helping us find who we are as artists. Working with him was like, “This guy is tapped into the same sort of stuff that I was doing as a little kid. He has this youthful energy, and these are things people responded to in the first place. Why am I trying to pretend I’m someone I’m not?” It just showed that filmmaking, no matter what budget level you’re at, is about personality. Without that, there’s nothing. Some of the most popular people in the entertainment industry are streamers, which is just personality. It’s just someone playing video games with their friends for 12 hours. But people tune in because there’s not as much of a distinction between what’s a movie, what’s TV, what’s a YouTube video. As long as it’s cool and they feel the human behind the thing, people are willing to give it a shot.

Corrente: The first time I saw Tucker, he was using a luggage cart as a skateboard and thrusting his pelvis, and I was like “Who the fuck is this guy? Either this guy and I are gonna be besties, or I’m not gonna like this guy.” Turned out that Tucker is, indeed, one of my favorite people. We played in bands together, we made shorts together and we’ve continued the collaboration now that we’re split apart on different coasts.

Filmmaker: Tucker, you have George in your first two movies, and in Why Are You Weird? he plays himself as one of your professors.

Bennett: He was down to show up for you. If you were like, “Hey, will you be in this movie?” he was like, “Sure. Can you make it easy for me to do?” “Yes. You want to play yourself and shoot it in your classroom?” “Fine.” And he would come! That wasn’t just us; he would do that for literally anybody who asked him. You felt like you were a part of his world. We met him at, like, year 40 of his career of teaching, so there were hundreds or thousands of students before us that I’m sure felt the same kind of connection, because that’s just who he was. He was just down for the cause. And he’d come to the movies, too. When they’d screen, he’d show up. “Great picture. You’re on your way!” That was an amazing resource and confidence boost.

Filmmaker: For Why Are You Weird?, you released the film online in 10-minute increments.

Bennett: This was when there was a 10-minute length cap on YouTube. We had started to see how people would pirate movies and upload them in little chunks. My collaborator Zach Shipko was involved with the net art scene and this online festival called JstChillin, where every month a different artist or entity would get access to the site to display whatever they wanted. Zach suggested we use his month to release the film we were just finishing, so we uploaded the film incrementally and embedded it on JstChillin. It’s perhaps one of the first feature films released directly to YouTube. I don’t if that’s true or not, but, you know, 2009. From participating in that, we got the attention and friendship of Eugene [Kotlyarenko], who went on to be a good supporter and an encouraging force, who has then also hired me for some stuff.

Filmmaker: Let’s jump ahead to Planet Heaven, where you and Zach reprise your roles from Why Are You Weird?

Bennett: We thought it would be funny to catch up with these pretentious art school kids 10 years later, after existing in the quote-unquote “workforce.” For me and Zach, it was after years of trying to fit ourselves into the quote-unquote “real world.” Like, maybe I’m not this auteur director, so maybe I can be an editor. How can I use my love of film and whatever technical knowledge I have to get a job and exist in the world? I had some awesome gigs and a lot of humiliating ones. Many people that we went to school with, like Zach and Chris, entered the tech industry. Living in LA, the wellness industry was such a thing.

We had a more straightforward kind of Office Space idea that we started filming, then COVID happened. We were like, “Let’s take a little break and wait for this thing to blow over. No use getting sick over this movie.” But then when it was like “This isn’t going away” [and] Zach had some other family responsibility, it became “How can we save this?” It had already been eight years of false starts and near-misses in terms of trying to get projects [going]; I was like “I can’t let this one die. The graveyard’s getting too big.” So, we reoriented it and introduced different characters. I decided to make it more of a patchwork thing, which I think was beneficial. I don’t think our original idea would have been as funny as it was once we started trying to incorporate more. An easy way to expand the world is to have a few scenes with a lot of different characters that illustrate a bunch of different facets of this world. That way, you can get away with [seeming to have] a more expansive world than you actually do. That was definitely applied to In the Glow of Darkness.

Filmmaker: With In the Glow of Darkness, you get much more ambitious with it. You have a fully-realized near-future world.

Bennett: Just having little custom props or a little custom poster with a band’s name does a lot to expand the world and make it real. Trying to create companies, figures and celebrities within that world does a lot to paint that bigger picture.

Filmmaker: It feels very handmade. Even when you incorporate AI ads, there’s still this kind of cheap, low-budget quality to it that adds a certain personality.

Bennett: You said the hot-button word. In the film, we saw a unique opportunity to use AI as the content slop that it is. We are by no means trying to pull a fast one or place it off as anything other than that, but hopefully it’s [used] in a way that is thematically relevant to the story. It matches the aesthetic. We’re talking about generated targeted ads from the subconscious and literal TV gobbledygook. Hopefully that paints the picture of this oppressive dystopian world. Because AI is an invasive species to humanity, and we wanted to comment on that and incorporate that into the humor of the film. Alternatively, it inspires more people to take a stance against it. We’re already seeing little title cards that are like “Absolutely no AI was used in this film,” “The following film was shot on all 35mm.” That’s great, too. I hope to make a film on film with no digital effects; that would be awesome. It’s just a matter of what’s appropriate for the story that you’re telling.

I was thinking about when I was a teenager reading Filmmaker. In 2003 there was this digital revolution. There were so many articles about “What does this miniDV technology mean? This is either gonna ruin cinema or save it!” As we saw, it was neither. It’s a tool. Of course, being able to shoot on miniDV and edit on your home computer opens up the floodgates for a lot lazy hack work, but also there was people who utilized this emerging technology in cool ways—Dogme 95, Timecode, The Last Broadcast, freakin’ Paranormal Activity.

Corrente: With the VFX, generally the workflow is Tucker did the Premiere stuff and I did the After Effects. It was interesting to incorporate the AI, because there’s so much lo-fi nonsense in what we’re doing, and having to motion-track a deliberately bad AI sign over a shaky handheld scene presented a series of intellectual and logistical challenges. As far as the slop part goes, AI kept getting better in our world, but we wanted to lock it into a particular quality in San Zokyo where it truly has to be recognizable as slop. There’s kind of a principled approach where if you see it on the screen in the movie, it means either someone’s seeing it on a screen or in their head, and there’s a fidelity limit. As we were trying to generate stuff, I had to lock into shitty local installs of outdated AI tech to maintain the vibe that we were trying to piece together.

Bennett: And it’s purposefully dated. As the technology becomes indistinguishable from a real CGI effect, I think it’s funny to have the time capsule of when it was janky, less threatening. It looks quaint by comparison. It’s supposed to look goofy and ugly and unrealistic. Seeing it at New/Next on the big screen, you’re seeing it deteriorate, and I think that is awesome. Like we say [about San Zokyo], it’s 15 minutes in the future, but 10 years in the past. It’s this weird amalgamation of dated technology that people are stuck in, at least in our future world.

Filmmaker: You really lean into that digital texture. You’re not grabbing an Alexa Mini and trying to make it look like 35mm. There’s many points in your movies where you film screens, too.

Bennett: I like the thumbprints and grease smears and reflections of it all. Glare and stuff like that. It’s a 1080 world. It’s also high frame rate, 30p—I’m trying to align myself with the homies Ang Lee and James Cameron, you know? There’s a certain tragic beauty in these plastic midrise apartment buildings that I see when I’m walking around Target, when I’m watching these AI YouTube ads that are everywhere. It’s lame, which is why it’s not often committed to film. It’s way cooler to show a payphone and bell-bottoms and film grain. That stuff has a timeless, cool quality. But just take a look around.

Filmmaker: My understanding is that you shot most of your previous work yourself, right?

Bennett: Yeah, and whoever I could get to hold the camera when I’m in the shot.

Filmmaker: You had Neal Wynne and David Borengasser shoot this one. Tell me about working with them.

Bennett: David is another one of our SFAI friends, a George disciple. Neal is more the DP who enjoys shooting people’s movies; David is a camera and gear whiz who’s just happy to help. On a great day, we had both of them, but when Neal had an actual paying job or something more important to do, we would be like “Okay, David, can you help out?” It’s awesome to have people you trust to know that the focus will be there. Maybe this is to my detriment as a director, but I want to have somebody locked off and in focus so I can be looking for the butterflies [Bennett mimics camera movements with his hands] and try to do my pan and little crazy moves and zooms. We did a lot of takes, not because of any performance issues, but because, like “Oh fuck, I messed up my little zoom from the doorknob to your eyeball. Let me do it again.” The actors would be like, “Do you want me to change anything?” “No, you’re perfect. It’s just me, I keep forgetting which way the focus goes.” But that’s how you get some cool, weird shots.

Filmmaker: Tell me about how this production came together, because it seems like you got working on it pretty quick after Planet Heaven.

Bennett: I had written it with a friend of mine in 2015. We were living in Oakland, and really it was a reaction to seeing the Bay Area change—the emergence of Twitter and this crazy tech industry, these mid-rise, blocky, 3D printed apartments appearing everywhere. I was like “Wow. This is the future world.” These are future communities where your apartment and Target and Ross Dress For Less all share the same parking lot. That was probably around the time that I got my first Amazon account and started realizing how targeted ads work, and YouTube introducing ads, and the first waves of streaming services introducing ads. I guess it was just me becoming aware of the algorithm of it all.

We wrote this epic Philip K. Dick extravaganza that we thought for sure someone would take one look at and give us a gazillion dollars to do. That wasn’t the case. But once Planet Heaven had some positive screenings, I was like “Okay, I gotta go back to that thing.” I never stopped thinking about it, and anytime a movie would have a similar element or a similar-sounding title it’d be like “No! Someone’s gonna get this idea about the meme drug and the targeted ads in the brain! Someone’s gonna have it before me and I’m gonna be miserable.” So, I just had to do it. I’m always trying to figure out what I can piece together without a crew or money. I could just shoot this stuff that will appear on TV later, the green screen video game world, these little things. Then, getting the opportunity to do The Code for Eugene gave me a little more encouragement, having someone else endorse me and pay and enlist me for my skills.

Corrente: I did some of the scoring for Planet Heaven, too, and really enjoyed working with Tucker again. We’d stayed in contact as friends, but hadn’t really been collaborating on projects for a while. When this film was in the works, I actually worked in tech and marketing and corporate America. So, it seemed like a pretty natural fit to come in and help update the script with some of the dialogue for the CEO characters—folks who I think are absolute caricatures, but maybe I could add a little real-world experience. I helped get the film made and came on as a producer. Then I implemented some of the same scoring principles we used for Planet Heaven, which was having a lot of music up front, as well as scoring based on character, so coming up with little themes for each character.

Bennett: I really like having the music before I shoot anything. I like to live in that world while I’m doing a script revision, while I’m doing a call sheet. It’s very useful for me to play it on the set for actors: “This is your theme.” I like to be able to point to these tactile things, especially because it is such a nutty movie that’s jumping around a lot. It was really important for me to have some sort of grounding with the characters. Also, I like to hear the music while I’m logging the footage and picking out shots. All the edits are super-rhythmic. We’re musicians, so that’s the main language we use to talk with each other.

Filmmaker: For your movies taking place in these digital worlds, they’re very physical. It seems like digital reality can affect the bodily functions of a person. I’m thinking of in Planet Heaven how the app makes people literally ooze goo, or In the Glow of Darkness you get a QR code on your lower back scanned and start tripping.

Bennett: You can’t understate David Cronenberg’s influence in sci-fi, heady stuff. He’s the master. I tend to get a little more spiritual than him but, as a foundation, what you consume as a human definitely has an effect on your body. Too much scrolling will literally give you back problems. Anything you put in is gonna sit with you and come out in some way. With speculative sci-fi, you imagine: What would happen if you turned the Bluetooth connection way up, trying to connect your brain to your phone? What would it be to link your psyche into a physical tattoo that has all your fears and fantasies and is ready to get tapped in by any sort of corporate interest? Just funny stuff, I think.

Corrente: I hope this film doesn’t come off as purely critical or satirical. These things that are pathetic or embarrassing also have merit. They bring a lot of joy to life. Doomscrolling is a fucking mixed bag. Obviously there is this great detriment to our collective and individual psychological and sociological health, but also there is a pleasure to it. Whether that is a perverse or a sick pleasure, whether it’s a harmful pleasure, there is still something there to celebrate. I hope that this film is both a mockery and a celebration of these things.

Bennett: There’s no shortage of stuff to watch, so you really gotta ask yourself, “What do you think is worth it for me to share so I’m not just taking up screentime from people?”

Filmmaker: Going back and watching your first film, it’s interesting that you guys released it online, because so much of the conversation at that point around mumblecore was about these young filmmakers infiltrating the film world with digital by going to South by Southwest and big festivals like that trying to get distribution. You guys just put the movie online. It’s even more anti-whatever the indie market was at that point.

Bennett: I remember watching the first Jackass movie in the theater and being like “Wow, this looks like shit!,” but having that be inspiring for me. Whenever I see the bar lowering, I’m like “Now’s my chance, it’s never been easier.” Who’s to say what would have happened had we tried to do South by Southwest? I’m sure it would’ve fallen through the cracks. But we knew we had friends and this one subset of internet artists who would watch that, so we leaned into that. It worked out the way it had to. Now YouTube content creator is a serious, million-dollar profession. But at that time, it was just a way we could finally get a movie out there. The further we go down the line, the less distinction there is between movies shot on film, shot on video. Every $300 million Warner Bros movie is beamed directly into your TV to watch. As long as it’s cool, and as long as you feel like there’s actually a human brain behind something, people are willing to take a risk on it. That’s what we’re banking on.

Publisher: Source link

Timothée Chalamet Gives a Career-Best Performance in Josh Safdie’s Intense Table Tennis Movie

Earlier this year, when accepting the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role for playing Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown, Timothée Chalamet gave a speech where he said he was “in…

Dec 5, 2025

Jason Bateman & Jude Law Descend Into Family Rot & Destructive Bonds In Netflix’s Tense New Drama

A gripping descent into personal ruin, the oppressive burden of cursed family baggage, and the corrosive bonds of brotherhood, Netflix’s “Black Rabbit” is an anxious, bruising portrait of loyalty that saves and destroys in equal measure—and arguably the drama of…

Dec 5, 2025

Christy Review | Flickreel

Christy is a well-acted biopic centered on a compelling figure. Even at more than two hours, though, I sensed something crucial was missing. It didn’t become clear what the narrative was lacking until the obligatory end text, mentioning that Christy…

Dec 3, 2025

Rhea Seehorn Successfully Carries the Sci-Fi Show’s Most Surprising Hour All by Herself

Editor's note: The below recap contains spoilers for Pluribus Episode 5.Happy early Pluribus day! Yes, you read that right — this week's episode of Vince Gilligan's Apple TV sci-fi show has dropped a whole two days ahead of schedule, likely…

Dec 3, 2025