Era Isn’t Aesthetic, It’s Behavior: How Cheryl Wenjing Xia Designs Period Worlds That Actually Breathe

Jan 11, 2026

Cheryl Wenjing Xia is a LA based Production Designer and graduate of ArtCenter College of Design. Xia approaches period design with a discipline that borders on forensic. For her, building the past is never about “vintage style” or mood-board nostalgia. It is, in her words, about behavior — how people lived, how they moved, what they touched, what broke, what was repaired, and how these choices left marks on space. When she designs period environments, she’s not recreating an era as an aesthetic. She’s rebuilding the conditions of life inside that era.

That mindset defined her work on a recent collaboration with director Daria Maximova: the construction of a 1920s Soviet residential hallway. The assignment was not small. The hallway needed to feel specific, local, and lived-in — not generic “old Europe,” not romantic ruin, not stage fakery. It had to carry the texture of shared poverty, collective housing, and controlled space. It had to breathe like 1920, not perform like 2025 pretending to be 1920.

Xia treated the hallway like a character.

At the macro level, she worked with Maximova to define the corridor’s entire architecture: its proportions, its linear depth, how narrow the run should feel between doors, how oppressive or generous the ceiling height should sit over the viewer. The wall surfaces were negotiated just as carefully. This was not a glossy paint job. It needed that layered plaster feel — slightly uneven, rubbed down by years of hands and heat and cheap repairs. Even the degree of staining near the baseboards became part of the conversation. The floor wasn’t just “tile,” it was an argument about tile: color temperature, wear pattern, and whether the glaze should read chipped or matte under camera.

Then the focus narrowed.

Doorways became their own study. Xia and Maximova had detailed discussions not just about which doors belonged in that time and place, but how they were built: panel shape, wood tone, proportion, hardware. She did not treat a door as a door. She treated it as evidence of who could afford to replace it and who couldn’t. The placement of the peephole (if there was one), the position and age of the door handle, the style and mounting of the buzzer — none of that was left to guesswork or modern instinct. Every piece had to line up with Soviet material culture of the 1920s. Every piece had to feel like it had been there before the camera ever arrived.

As a foreign production designer working in a Soviet-era setting, Xia was acutely aware that inauthentic detail reads immediately, even subconsciously. That meant research wasn’t optional. It was the build. She spent long hours gathering photographic references, digging into historical visuals, and pulling stills from period films to identify what was plausible, what was common, and — just as importantly — what would be wrong. That process shaped not only the big choices (door frames, tile type, plaster texture) but also the micro-decisions: bells, latches, screws, finishes.

And the work did not happen from a laptop. Xia and her team went physically into prop houses, sometimes staying for hours at a time to chase down the right object, the right weight, the right patina. The process was obsessive and, by necessity, slow. The corridor couldn’t look dressed. It had to look accumulated. She also hit multiple building-material suppliers and salvage sources, not just for budget reasons but because new stock was unusable if it looked “new.” A wrong surface gives you away faster than a wrong reference.

A still from the short film “Cucumber” Directed by Daria Maximova

Her collaboration with Maximova continued into a different narrative space — a FedEx commercial built around a very particular character: a taxidermist living in a present-day New York apartment that feels psychologically anchored in the 1920s. The tone of this project was radically different. This was not strict realism. This was a world that existed somewhere between silent film era unease and contemporary isolation — strange, private, a little haunted. The creative language pulled from early cinema, German Expressionism, and something deliberately uncanny, almost museum-like.

To build that interior, Xia and Maximova did what they always do: they went looking for physical input. They walked Los Angeles’ Museum of Jurassic Technology. They visited Vulture Culture oddities spaces. They gathered textures from places that felt wrong in the right way — too quiet, too curated, too still. Those visits weren’t “inspiration trips.” They were spatial studies. The question wasn’t “what looks cool?” The question was “how does someone like this actually arrange their life?”

Together, they mapped the apartment not just as a layout but as a lived pattern. Where does the table sit in relation to the main work surface. Which window is usable light and which is just mood. Where do tools collect. What corner becomes ritual space. The blocking of objects had to match the daily motion of a solitary, meticulous person who lives with specimens.

In that same project, Xia took period thinking all the way down to the hand scale. She fabricated the key prop for the spot: a hollow, heart-shaped taxidermy specimen vessel. It wasn’t outsourced. It was built. She combined 3D printing with hand-finishing to get the exact hybrid language the story needed — part clinical, part intimate, part unsettling. She then dressed it using whatever carried the right organic truth: fallen branches and leaves collected on location, fragments of insect material, even loose strands of hair. Nothing glossy. Nothing “Halloween store.” Every added element needed to feel like it had been handled, cataloged, and kept.

Because the final spot was shot in black and white, Xia also painted the piece in grayscale under live phone camera tests, checking contrast and value instead of hue. She wasn’t painting for the human eye on set. She was painting for the lens, for the grade, for what the audience would actually see.

The result impressed the entire team — not because the prop was complicated, but because it felt disturbingly believable. It felt owned.

Taken together, these projects say something essential about Xia’s practice. She is not just collecting era-correct objects. She is reconstructing how those objects were used, at what point in their lifespan, and under what emotional conditions. She treats period not as a visual filter, but as a living system with rules.

The heart-shaped sculpture for a Fedex commercial directed by Daria Maximova

For Cheryl Wenjing Xia, “period design” is never about arranging old-looking objects and capturing a pretty nostalgic frame. Her target is stricter, and more intimate: she wants the space to be lived the way it would have been lived in that era — claimed, worn down, repaired, improvised. She’s not chasing “does it look like the past,” she’s chasing “did this past actually function like this.” That’s why she will spend the kind of time other departments would call excessive on things like the height of a doorbell in a 1920s Soviet hallway, the direction of wear on floor tile, or a single stray hair sealed inside a heart-shaped specimen prop. For her, those details decide whether an audience believes the world or doesn’t. And that’s the difference: environments she builds don’t just resemble an era, they behave like one. They breathe on camera, they carry fatigue and memory, they feel inhabited. A hallway that should exist in 1920s Soviet housing. A New York apartment that still thinks in silent-film logic. This is her signature as a production designer: era isn’t a style choice, it’s behavior — and space isn’t background, it’s narrative.

To learn more about Cheryl Wenjing Xia’s work, or to collaborate, contact [email protected] or visit www.xia2rt.com

Publisher: Source link

‘The Rookie’s Best Season 8 Episode Goes Completely Different With Full Zombie Horror

Editor's Note: The following contains spoilers for The Rookie Season 8, Episode 10.It's crucial for procedurals to come up with a winning formula that entices viewers to tune in every week. But it's just as important for these types of…

Mar 13, 2026

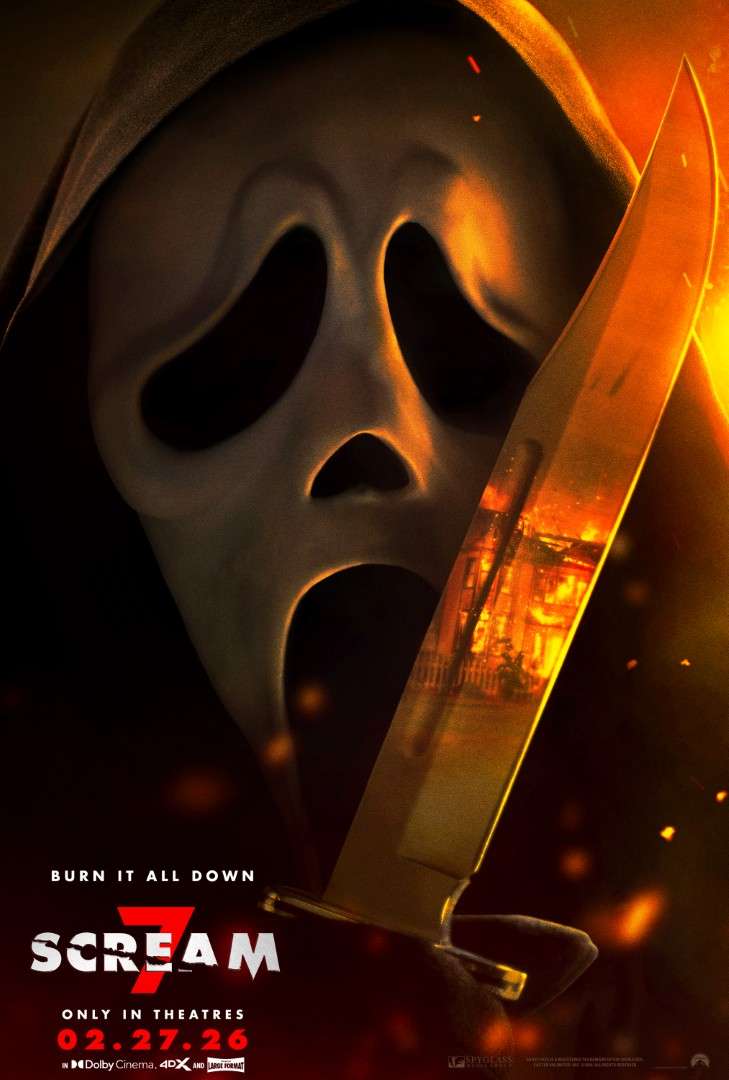

Sidney Prescott Leads a Brutal Throwback

Walking into Scream 7, I wasn’t sure if this entry would be a new reinvention. I know I wanted tension. I know I wanted that uneasy calm before the snap. And most of all, I wanted to see why Sidney…

Mar 13, 2026

Eggs – Film Threat

In writer-director-star James Clair’s short drama Eggs, a man struggling to rebuild his life finds his quiet mornings turning into strange conversations with the very eggs he is meant to cook. I mean, they want him to eat them. So…

Mar 11, 2026

Ethan Hawke Elevates A Rugged, Predictable Gold-Run Survivalist Western[Sundance]

As far as one can tell, Murphy (Ethan Hawke), a father, WWI veteran, and avid car mechanic, has never encountered an insurmountable challenge. Living in Eugene, Oregon, in 1933, four years into the Great Depression, Murphy and his young daughter,…

Mar 11, 2026