Michael Mann Reflects on ‘The Insider’ 25 Years Later [Exclusive]

Dec 5, 2024

The Big Picture

Collider’s Steve Weintraub speaks with Michael Mann in honor of

The Insider

‘s 25th anniversary.

In this interview, Mann discusses the behind-the-scenes making of

The Insider

, from campaigns launched against the movie to a 300-page annotated screenplay.

The filmmaker also shares details on

The Keep

,

Collateral

, and updates on

Heat 2

.

In 1999, filmmaker and screenwriter Michael Mann released what would become one of the greatest dramas of its time. Starring Al Pacino, Russell Crowe, and Christopher Plummer, Mann and co-writer Eric Roth adapted the story of chemistry teacher and whistle-blower Jeffrey Wigand (portrayed on screen by Crowe) into a feature film that went on to garner seven Academy Award nominations. To celebrate the 25th anniversary of The Insider, Collider’s Steve Weintraub had the pleasure of speaking with the esteemed director about his experience throughout the tumultuous production.

During their conversation, which you can read below, Mann speaks in-depth on everything about the process from first getting it greenlit to translating the stakes of the story into a visual language. Due to the nature of the material, Mann reveals he and Roth took a very Lowell Bergman (portrayed in the film by Pacino) approach to the screenplay, which became a 300-page document, including annotations. He also reveals how “there was a campaign against the movie launched by [Mike] Wallace and [Don] Hewitt,” an infiltration into their heavily guarded editing rooms by a law firm in the film, and discusses whether a movie like The Insider could be made today.

In addition to The Insider, Mann also reflects on his favorite Stanley Kubrick films, his time making The Keep and the lessons learned from that production, Collateral, and shares an update on the status of Heat 2. For all of this and much more, check out the full interview below.

This Stanley Kubrick Film Inspired Michael Mann to Make Movies

COLLIDER: I like to throw some curveballs at the beginning. I read that you saw Dr. Strangelove earlier in your life and it had an impact on you, and it helped you get into filmmaking. I’m curious if that’s your favorite Stanley Kubrick movie or if you have a different one that’s your favorite.

MICHAEL MANN: It probably still is my favorite Stanley Kubrick movie. The first Stanley Kubrick movie I ever saw was Paths of Glory, and I particularly was interested in it because it’s probably the best adaptation of a novel. Reading it, it’s a perfect kind of a recombinant recreation into a two-hour narrative. The original novel’s by Humphrey Cobb. Yes. I think Strangelove still is my favorite. I think so.

How ‘The Keep’ Changed Michael Mann’s Filmmaking

I know that when you directed The Keep , you originally had a much longer cut, but it’s never seen the light of day. Do you still have a copy of the longer cut, or does it no longer exist?

MANN: I don’t even know. I’d have to dig into our archives to find out. We have a pretty spectacular archive. We saved everything, but I don’t know how much I’ve saved on The Keep. The poignant tragedy that came was that the visual effects genius who worked on it, Wally Veevers — who was a spectacular guy, who goes all the way back from The Shape of Things to Come all the way through 2001 [A Space Odyssey] — died halfway through post. He had many esoteric forms of creating some of the visual effects, and it was only through the generosity of the visual effects community in England that we were able even to finish the picture. A lot of people who knew and respected Wally dove in to try to figure some of this out. So, it was a bizarre project.

You’ve expressed dissatisfaction with the final cut of The Keep , and I’m curious, did your experience on that project turn you towards more grounded genres permanently?

MANN: No, it had nothing to do with that. It had to do with going forward and shooting a movie before the screenplay’s ready. There was a one-year window in which to get the movie up and running and finished because of something that had to do with Paramount and a UK tax deal. I agreed to do that and was trying to finish the screenplay at the same time. So, no, it’s nothing to do with gothic or sci-fi subject matter.

One of the big thrills of that was to work with John Box, who was a fantastic production designer with three Academy Awards, Lawrence of Arabia, Oliver Twist, A Man for All Seasons. What an honor. A lot of things about it were new that we did, especially the design influence of German Expressionism and the exploitation of Albrecht Speer, the Nazi architect. I was very interested in the causes of fascism, the nature of its malign appeal to cultures in distress and a form of mass schizophrenia, and to try to express that in the form of a Freudian fairy tale, meaning not metaphor or allegory. It was informed by reading Bruno Bettleheim and was an interesting challenge. If I made it again, it would be much better. [Laughs]

I really, really hope that one day you will go into your archives and see what you have because I would love to see if there is a longer cut. The problem obviously is VFX aren’t done, music’s not done, but it’s definitely something that I’m sure fans would love to see, even in a rough cut.

MANN: So, since The Keep, after that, I’ve always been much more careful about not going forward to something until it’s ready.

Related Michael Mann’s Only Horror Movie Is a Brilliant Disaster The Oscar-nominated filmmaker behind ‘Heat’ and ‘Collateral’ wasn’t afraid to get scary.

As a fan of your work, only some of your films are available in 4K. Will I ever get a 4K version of The Insider ? Will I get a 4K version of The Last of the Mohicans or Thief , just to name a few?

MANN: I didn’t realize The Last of the Mohicans wasn’t available in 4K.

If it is, I couldn’t find it.

MANN: We absolutely have to pursue that. Same thing with Insider. The best cut of The Last of the Mohicans is the director’s cut. It’s slightly shorter.

The Insider looks good, but it’s not 4K. I watched it to talk to you, and I’ve been recently watching some stuff in 4K, and it’s just blown me away, just the quality of the picture.

MANN: How large a screen are you looking at it on?

I have an 80-something inch OLED television. I watch a lot of stuff for work, so I invested real money in that.

MANN: Yeah, you’re looking at it on the right system and all that. The answer 80-inch or the 77-inch Sony A95L is really the way to see it. That does make a big difference, though. Because of this interview, I have to go call Disney at the beginning of the week and tell them we should do it. We should have a 4K of The Insider for sure.

The Insider definitely does not exist in 4K. They put out Heat and a few things from your resume, but there are plenty that need it, and I would love for you to look into it.

Michael Mann Explains the Ways He Filmed ‘The Insider’

You have been in the forefront of digital filmmaking, and you were so ahead of the curve. I’m not sure if you’re aware, but Danny Boyle just shot 28 Years Later using an iPhone and very large lenses. Do you feel like, “Damn it, that should be me,” or are you like, “I can’t wait to see that?”

MANN: He did it for a reason. The enthusiasm for it has to come from the content. The beating heart of the content has got to be the reason and the turn-on to reach for a more expressive form — there is certainly that with Collateral — other than the internal impulse to always want to push the envelope and express something in a newer and exciting way. But the impulse to do it has to be, for it to be valid and for the outcome to be authentic, there has to be story drive.

With Collateral, it was to tell this story in nighttime LA. Really see into the alienation and surreal poetry of the LA night. The difference is I had shot that on film, on photochemical, as opposed to doing the R&D, and it required three months of that for us to be able to do what we did with Stone Age digital equipment. Because it’s, like, late afternoon in the UK, in the winter, at night in LA. You would never see any of that. You wouldn’t have depth of field. You wouldn’t get the wonderful alienation, very emotionally poignant alienation about what the sky looks like, the whole landscape at night looks like. It’s very surreal. So, that was the impulse to do it. And what made the exploration fascinating was to discover a new aesthetic through the technology. We were working with Sony F900s, which were like a cheap newsreel camera, because that’s all there was around. Then, for some interiors, I used the Viper, which has a Thompson, a Dutch chip, and rendered mid-range tones quite luminously, a lot better. Dion Beebe, we worked together on that and we worked together on Miami Vice following Collateral.

Then Insider, that, too, started with the following: I know that the true, very dramatic threat to Jeffrey Wigand, and the existential search and confrontation Bergman goes through, and, “Why am I doing this?” We take 60 Minutes out of the equation and no one returns the phone call, the whole questioning, which eventually manifests itself in the ending of the film, where even though he gets it on the air, he’s going to leave, I know what that means inside of a human life. In Wigand’s case, here’s what happens when a Fortune 500 company decides they’re going to destroy you. So, then it becomes, “How do I externalize this? How do I communicate and express this in everything to do with the film form,” which isn’t just visual, it’s music, it’s how the effects are handled, it’s everything, meaning that I want to bring the audience into a very subjective state for them to be Jeffrey Wigand, this awkward person. See how he sees, hear how he hears…

And so, that led to the whole use of the lenses and the way the film is shot. When you’re over the shoulders — I wanted you to be that person who’s listening, as well as taking in Dick Scruggs in Scruggs’ kitchen when he tells them, “I know how you feel. This may not go well. They can take the money that you would spend on your kids’ education or medical.” He’s basically getting all the reasons why he shouldn’t testify. So, that’s really where this comes from. So, whether it’s Collateral with digital, which is external on one LA night, or whether it’s looking for innovative ways to create the dramatic experience of inner life in Insider, shoot the people of Insider, it’s to bring you within these people’s lives. And, do so internally. Here’s the standard. You know what really was there, you know the life-altering lethal threat of what Brown & Williamson were doing to him to compel him to shut up. And the assault does alter them. They never do quite recover. That that can be dramatized and effectively expressed, that was what pushed the film form.

How Michael Mann Puts the Audience Into the Minds of His Characters

“It becomes the visual, it becomes the editing, it becomes the music.”

Image via Buena Vista Pictures

Do you remember what shot or sequence in The Insider was the toughest to film and why?

MANN: One of the most challenging to film was when Jeffrey Wigand is shooting his interview. I wanted to be with Jeffrey Wigand to feel him. I wanted to feel Lowell watching that monitor and watching Jeffrey Wigand and to be aware of everything, and Mike Wallace. To be aware of everything in duplicate, if you like, rather than just have one objective of what I’ve got the camera on. And so that was challenging there in a really great symmetrical way. The courtroom scene in Pascagoula, in a way, because so much hinged on that performance. And Bruce McGill was spectacular. He actually ruptured himself from that explosive dialogue when he says, “Wipe that smile off your face.” That whole speech.

One of my favorite scenes — it wasn’t challenging to shoot, there’s just a lot riding on it — is, I think, one of the best Al Pacino monologues, when he talks to Don Hewitt and Wallace, “Am I a newsman? Are we a news organization? You pay me to get guys like Wigand and draw them out, to get them to trust us, to get them to go on television.” That then ends with the betrayal where Wallace says, “Lowell, I’m with Don on this.” So, there was a lot riding on that.

Another is a man alone leaves work and goes home as if it’s the routine end of a normal day but we experience an unexplained subterranean tension saying something ballistic is going on within – only to discover much later when he tells his wife on the driveway he’s been fired and their world has ended.

I think maybe one of the most challenging things was to be inside of Jeffrey Wigand’s mind, to have the almost, it’s not magical realism, but to be so subjective that we are him when he makes that decision in front of Dick Scruggs’ house, and then he’s driving to court. For me, that says, “Okay, I’ve made a decision…” — we all have done this in our lives — “I’ve made a decision, and now I’m going to enact this. And, of course, on the way there, my mind is trying to digress and put my attention on something else because I now have some fear or wariness about this decision I’ve just made and where it’s going to take me and the consequences of it.” So, we evade, we look at fence posts going by, it happens to be the fence post of a cemetery. You know how you look out at the ocean to make a decision. That really was Dick Scruggs’ house, by the way. It really is where Jeffrey Wigand made a decision. I couldn’t have designed it better myself if I tried than a real place. So, that’s where we shot at it, all of which got wiped out during Katrina, by the way.

So, those were probably the most challenging — to subjectivize the audience within the sensitivity and consciousness of Wigand. The moment when he’s coming back to Louisville and he may get arrested, he may get put in prison. There’s glass on the side of the road, and there’s a burning car, apropos of nothing. A symbol that is not a metaphor pops into one’s head. Those are the things that take our attention when we’re stressed. What do we do? What do we think of? Can I externalize that cinematically? Because if I can, then I could bring you inside the state of being Jeffrey Wigand, and that’s the objective. So, that was my mission. Constantly looking for those truthful, authentic moments to create, again, like the glass outside on the road or the burning car, or he looks at the fence posts going by, it becomes the visual, it becomes the editing, it becomes the music. Bringing that together organically, unifying that into some moment that’s going to live, to make you feel that if you were Jeffrey Wigand this is exactly what you’d be doing, that becomes a conduit.

Related Tom Cruise’s Villainous Turn in Michael Mann’s ‘Collateral’ Remains One of His Best Tom Cruise is a respected action hero with a multitude of iconic performances, but this Michael Mann film shows he can play evil just as well.

One of the things about the film, which I think a lot of people don’t realize, is that it’s basically people talking. There are some courtroom scenes, there are some faxes sent, there’s some debate in newsrooms, but there are no big moments that a studio likes to sell in the marketing. How tough was it to actually get the green light on this thing from a studio because you don’t have the typical elements that they like to sell with?

MANN: I’ll tell you what, I was very fortunate. Joe Roth, at that moment in time, went to work at Disney and took over underneath Michael Ovitz when Michael Ovitz was brought to Disney by Michael Eisner. Ovitz had been my agent, and he’d just left CAA to go take over Disney, and he hired Joe Roth. Joe Roth ran 20th when I made The Last of the Mohicans. I walked into Joe’s office with Roger Birnbaum — the two of them were running 20th — and I said, “There hasn’t been a period picture like this in 15 years. It’s not a western. I want to do The Last of the Mohicans.” They said, “Wow, what a great idea. Let’s go.” I mean, that’s how difficult it was to launch Mohicans. “Here’s the screenplay.” “The screenplay’s great. Let’s make the movie.” It kind of went like that. So, there was a lot of trust. A tragic romantic tale rooted in authenticity because nothing was as dramatic as the cutting-edge real reality of 1757 and the power of the ending with the double dilemmas of family vengeance and the rival strategies to deal with the demise of your people. Joe said, “Here’s the campaign: love story in a war zone.” That stunning clarity of how to sell it produced a brilliant marketing campaign and commercial success, except Diller inexplicably sold off foreign to a lot of disappointment since it did extremely well.

Then, when I went to do The Insider, Joe read Eric Roth’s and my screenplay, and he loved the screenplay. We had a meeting, and Joe said, “The movie is going to cost about $65 million.” “Will we ever make our money back?” And I said, “I don’t know.” He said, “Fuck it, let’s make it anyway.”

[Laughs] I love that.

MANN: He loved the screenplay. I must say, Eric Roth and I were joined at the hip day and night writing this. It’s the best coworking experience with a partner and dear friend I ever had – both as a combination of Eric’s brilliance, personality, our personalities, and the sensational grit and intelligence of the real people we were making into our characters. We made the movie. We garnered seven or eight Academy nominations. At that point, Roth was gone from Disney. Eisner was there, and there was a campaign against the movie launched by Wallace and Hewitt. People at Disney were getting uninvited to brunches at the Hamptons that summer because they let “those Commies” – according to Hewitt I think, Bergman, Mann and Roth, make the film. Disney didn’t really support it during the Academy season. We had an awards budget of about $100,000 to $150,000. I’m not all that wound up about winning statues. The affirmation of peers is thoroughly wonderful but the big high is the movie. So, Eric Roth and I would put on black tie, and go to a series of events and lose…except the WGA and BAFTA and I think New York Critics.

I will say, though, that there are many films that come out that are popular at the time but don’t stand the test of time. The thing about The Insider is, I just rewatched it, it’s 25 years later, and it’s still awesome. It’s one of those that people are going to watch for years and years for future decades because it captures a time that is just gone.

A 300-Page Annotated Screenplay of ‘The Insider’ Exists

“There was some courage at Disney in how we approached it.”

Image via Buena Vista Distributions

One of the things about this film, and I’m so curious about it, is you’re telling a real story about real people, and you’re dealing with big corporations that could easily sue the makers of the movie. What the hell was it like making a movie where you needed the lawyers at Disney and whoever at Fox to basically have your back and sign off? This whole thing could have easily gone off the rails if the lawyers said no.

MANN: That’s a really great question, and I’ll tell you why. We were very conscious of it the whole time. First of all, Brown & Williamson’s annual revenues exceeded the book value of Disney. The General Counsel of Disney and I worked to corroborate absolutely every single thing in the screenplay. When we wrote the screenplay, we were writing it with the standard of corroboration that Lowell Bergman applies to everything he does, which means he would never accept something as truthful, to report unless he had corroborated it about three times. He really had to know something was true before he represented it. So, Eric Roth and I might come up with a dramatic device, but if Lowell couldn’t prove that that really happened and had two or three people to validate that, it was out. Eric Roth and I disciplined ourselves the same way — we didn’t put it in there. No dramatic license. And so, you don’t know. There’s an ambiguity about the bullet in the mailbox, so you don’t know in the film really where that bullet came from. There are two sources that tell us private investigators working for Big Tobacco put it there, but it wasn’t definite enough to say they definitely did it. So, we made its source ambiguous.

So, we produced a document, which is the screenplay with all the corroboration annotated. It was used for years in the Columbia School of Journalism. I did a lecture there. I forget who it was with, it was a nonfiction writer who was very, very well known, who was teaching journalism at Columbia at the time. Now we’re talking about it, I’ve got to unearth that thing. It’s an amazing document because the screenplay was 150 pages — this corroborated version is about 300 pages.

That’s the kind of thing that you should put online and share just to show people if you want to do something like that, or put it out as a book. I’m sure people would love to read that.

MANN: That’s good. So, that’s how it was handled. There was courage at Disney in how we approached it. There was some nervousness — there was a threatening letter. Film operations are relatively porous, and I didn’t want our editing room or anything we were doing to be porous. So, we had security that was pretty elaborate before you could walk into those editing rooms and walk into our office. I had a guy who had just retired — he set up the security of the US embassy in Moscow — and he worked on the whole physical structure of our editing. And then I found out later that somebody had penetrated what we were doing. One of the law firms we talk about in the movie that’s based in Kansas City hired somebody who came to work as a transcriber to do a lot of dictation. Anyway, that’s what happened. But they waged a campaign.

Could ‘The Insider’ Be Made Today?

Image via Buena Vista Pictures

Do you think a movie like The Insider could have been made today?

MANN: I don’t know. The Insider, strangely, is very relevant today. I don’t know that it would be made today at that scale, which is the right scale for that picture and that story. I mean, it’s relevant, not just in the headlines — I’m thinking about Washington Post and LA Times last week. Patrick, by the way, used to be my landlord for our production office back when we were starting to do Heat and working out of a modest home that he and his wife then owned in ‘95. It’s a different world. There’s a truth-telling standard that is a critical factor in Lowell Bergman’s life and in Jeffrey Wigand’s life for two very different reasons — very, very different people. Wigand is trying to score on an external scoreboard set by his father, and Lowell has a totally internalized standard that generates who he is to himself. But objective reality, truth today, has lost its agency to social media and the bizarre current of feely-feely reactions.

But a truth-telling standard, objective reality, I come from that world and live in that world. That’s not the current world. The current world is, “I don’t care if it’s true or not, it’s how the words make me feel. So, if they make me feel bad, poor baby, then those words shouldn’t be there and the regard for that dominates issues like the real human condition and circumstances working and middle-class people struggle through to do well for themselves and their families.” This is not new or original thinking. I think Carville has it mostly right. That’s where we are today. That’s not a place that I consider a home. So, you know what? I think maybe the results of this recent election, the focus is going to shift back towards objective reality a bit more. It’s what is relevant, a more Kantian worldview than this much softer place that we’ve been in. When a film like The Insider works and how it’s worked on you has relevance and does stand the test of time, I think that’s what’s important. So, I don’t know if that film would be made today or not.

I read Mike Wallace said that two-thirds of the film is accurate, but he objected that he would have taken so long to protest CBS corporate policies. Do you agree with what he’s saying or is he just trying to protect himself?

MANN: I had a very interesting relationship with Wallace. The film is dead-accurate. Lowell said to me and Eric when we were writing, “If you think people in Hollywood have thin skin, wait ‘til you meet the guys I work with.” So, I met Wallace, and we would routinely talk. I happily supplied him our screenplay. Some of the conversations were hilarious. At one point, I was location scouting and I was talking with Wallace and he was running down one scene and saying, quite sarcastically, “Thank God I had Lowell Bergman with me every step of the way to shine a light on the path of moral rectitude.” And I said, “Mike, listen, do I have your permission to put that dialogue in your character’s mouth and put it in the screenplay?” [Laughs] He said, “Absolutely, my boy.” So, that was the tone of it.

Another time when we were shooting on location in New York, we rented an apartment and I got in the elevator to go to work. It stopped one floor below, and Don Hewitt walked into the elevator. It turns out he lived in the same building, I had no idea. And so, we’re descending through four floors to the ground level where there’s a van to take me on a location scout, I’m standing next to Don Hewitt. He does not know who I am. I know who he is. As the milliseconds are ticking by, I’m thinking, “I don’t have to say anything.” Well, you can’t really say nothing. So, I turned to him and said, “Mr. Hewitt, I want to introduce myself. I’m Michael Mann.” He was taken aback for maybe half a second. Then he threw his arm around me like I was his best friend in the world, and as we walked out through the lobby together he launched into a diatribe about, “That fucking Lowell Bergman.” His recovery took half a second. So, there were a lot of incidents like that during the making of it.

It’s sad that Wallace was so sensitive to his portrayal. He’s fine in the movie. He’s human. He slipped and made up for it with charm and brio. He was a genius at what he did. Most people who see the movie do not have the negative impression about Mike that he imagined. He’s a human being like everybody else. That’s what the whole movie is about. Particularly with the flawed character like Jeffrey Wigand. If Jeffrey Wigand was an iconic, cliched, heroic whistle-blower, there would have been zero point to make the movie. I wouldn’t have done it. Wigand was compromised internally. He had negotiated with himself – as a man who had an elevated regard for “men of science” – and now he’s working to addict people to tobacco but still wants to consider himself as a scientist with integrity. He and Lowell don’t particularly like each other. He’s awkward within his own body. And Lowell has his own vanity with a vaunted superego. But Wigand stands up. Lowell, in spite of Wigand, defends Wigand anyway. And so, what Wallace goes through is a failing that he then recovers from with tremendous brio and aplomb. I liked him so much, I wish he had not been so sensitized to his misperception by public. He was fine.

When I was working with Muhammad Ali when I did Ali, Ali was insistent that he did not want hagiography. He insisted on a portrait of himself, warts and all. He insisted on that. He was almost proud of the failings he had because most of those he overcame. At one point, I said to him, “Of everything that we’re covering in the screenplay, what do you regret the most?” And he said, “What I regret the most, the biggest tragedy, was my rejection of Malcolm X in Accra, Ghana, and that I never got to apologize and make up with him for that.” Because Malcolm was killed not long afterward.

“Everything Small Became Critical” in ‘The Insider’

“There’s nothing that’s by accident.”

Image via Buena Vista Pictures

A lot of the movie is handheld. How much are you thinking about your shot selection before stepping on set, and how much are you finding it in the moment? How much are you and Dante [Spinotti] on this particular project discussing how you want to shoot something and how much have you already planned out how everything is going to go before you get there?

MANN: I plan out everything in great detail. I work pretty much on a European method of directing. I compose all the shots and operate as well. The director of photography is a lighting cameraman. He lights. In Dante’s case on Insider, he paints with light. Literally. He does not compose shots. That’s the director’s most intimate expression. And so how I’m going to shoot and how to visualize this is worked out in great detail with a lot of preparation ahead of time. It’s going to affect the selection of lenses. I wanted to illuminate exterior daylight in ways that hadn’t been done since maybe the 1930s, to heighten particular dialogue moments, to illuminate motes of dust in the air in daytime locations in Manhattan with arc lamps from the 1940s. There was an elaborate design to how we lit. Everything small had to be artistically articulated to bring the audience intensely inside two-hours and 45-minutes of talking people. Scene by scene. So, every small thing became critical. It would be anyway, but it was particularly the case in how expressionistic, standard reality had to be pushed. If the film works, that’s why that’s why the film works.

For example, if you take a look at the scene where Lowell Bergman (Al) is sitting in the lobby of the Seelbach hotel in his first meeting with Wigand. He’s turning the page of a newspaper. The way that’s lit and shot, we designed that probably a month before we did it. There’s an overexposure of the highlights on the newspaper. That’s also amplified with the sound of the turning of the page. Nothing by accident. Everything is, I don’t want to say designed because there’s more than that. Now, having done all that prep, of course, on the day, to me, the advantage of the preparation ahead of time is that it gives you a platform in which you can spontaneously respond to inspirations that show up on the day. So, it gives me the freedom to be spontaneous by being spontaneous on a platform of pretty thorough preparation.

I love talking about editing because it’s ultimately where it all comes together, and for some of your films, you have released extended cuts or director’s cuts or multiple versions, but as far as I know, The Insider has always just been the cut that you released. I’m curious how this film got shaped in the editing room. Did you have a much longer cut? Did you end up with a lot of deleted scenes?

MANN: I don’t think there are any deleted scenes. When the film really works, I don’t change a frame. There’s no re-editing on Heat, there’s no re-editing on Insider. The ending of Last the Mohicans was always a problem. This all goes back to the screenplay. When the script is really 100%, you wind up not changing anything. So, I’ve probably re-edited the ending of Last of the Mohicans a couple of times, and then the last version of Ali is most political and it’s the best version. It’s a bit shorter and it’s more political — it identifies particularly the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and stuff that happens in the middle of it. But the editing, to me, you make the film in the editing room, and I’d be working with Billy Goldenberg and Paul Rubell.

One of the last lines of this film is, “What got broken here doesn’t go back together.” It seems more powerful than ever because 60 Minutes at the time, at 30 million viewers, you could change the world with one of their stories. The ending of the film is very powerful and really captures that moment.

MANN: Yeah, I think it does. It’s unexpected, and yet it’s dead right. There’s a high energy to it – like the unexpected right outcome – even though it’s obviously a downturn. You know that Wallace and Bergman still have high regard and caring for each other in a complicated way. And Bergman’s career never really did recover. It’s life. It’s the powerful, inevitable way that life is sometimes. Lowell says to him, “What am I going to tell the next witness, Mike? Don’t worry, we have your back. You’ll be okay. Maybe? This doesn’t go back together again.” That’s his last line, and then this fantastic piece of music I found to use as he’s walking through the slowly revolving door into a brilliantly lit sidewalk by Massive Attack.

But it’s also that time and place where 60 Minutes had so much power, and now, you could put out a massive story in the New York Times, and it’s gone in 24 hours. It’s just crazy how much the world has changed.

MANN: The world’s changed so much. I mean, the silly choices of Donald Trump this week… You know. The thought doesn’t even occur, “Can they even begin to do the job?” His appointments, I mean. It’s shrunk. Institutional media has aged out. Social media has compressed us into small cohorts of large numbers vulnerable to the ebb and flow of untruth and attitude that can catch fire and inflame.

I know. Believe me, I know.

MANN: [Laughs] It bankrupted satire and pastiche, half the stuff that’s real.

Michael Mann Is Polishing Act 4 of ‘Heat 2’

I think Heat is a masterpiece in every possible way, and I know that you are developing and working on a sequel, prequel-sequel, Heat 2 . I just have to ask you, what’s the status of that project? What can you tell our audience?

MANN: I’m finishing the screenplay, and at 2:30 this morning, it woke me up in the middle of the night. So, I wound up driving through LA at 3 a.m., which is fantastic. There are no cars. Ended up at Canter’s Delicatessen because that’s the only thing open 24 hours. Then I sat in a booth and wrote there until about 9:00 this morning, trying to finish act four. It was ironic because it’s the exact same booth I sat in when I wrote the first couple episodes of Starsky & Hutch back in the 1970s. Then The Jericho Mile and probably some early drafts of Heat. I had a favorite waitress named Jeannie who put two sons through medical school waitressing there and playing poker in Gardena. [Laughs] So, sometimes you’re driving through the streets of LA at night, and a coyote runs across it.

Can I ask, do you freehand write, or are you using a laptop?

MANN: No, I have my own thing. I use a combination of outlining, dictation, and constantly revising.

Do you think it could be filming next year? Are you at that stage? Do you have the financing? Do you have the studio?

MANN: I’m doing this at Warner Bros.

So, it’s definitely going?

MANN: Nothing’s definitely going because the sky may fall. But Heat 2 is at Warner Bros. I’m writing the screenplay for them, and hopefully, we will go forward as soon as possible.

The Insider is available for rent or purchase on Prime Video.

A research chemist comes under personal and professional attack when he decides to appear in a 60 Minutes exposé on Big Tobacco.Release Date November 5, 1999 Director Michael Mann Runtime 157 Minutes Writers Marie Brenner , Eric Roth , Michael Mann

Publisher: Source link

‘The Rookie’s Best Season 8 Episode Goes Completely Different With Full Zombie Horror

Editor's Note: The following contains spoilers for The Rookie Season 8, Episode 10.It's crucial for procedurals to come up with a winning formula that entices viewers to tune in every week. But it's just as important for these types of…

Mar 13, 2026

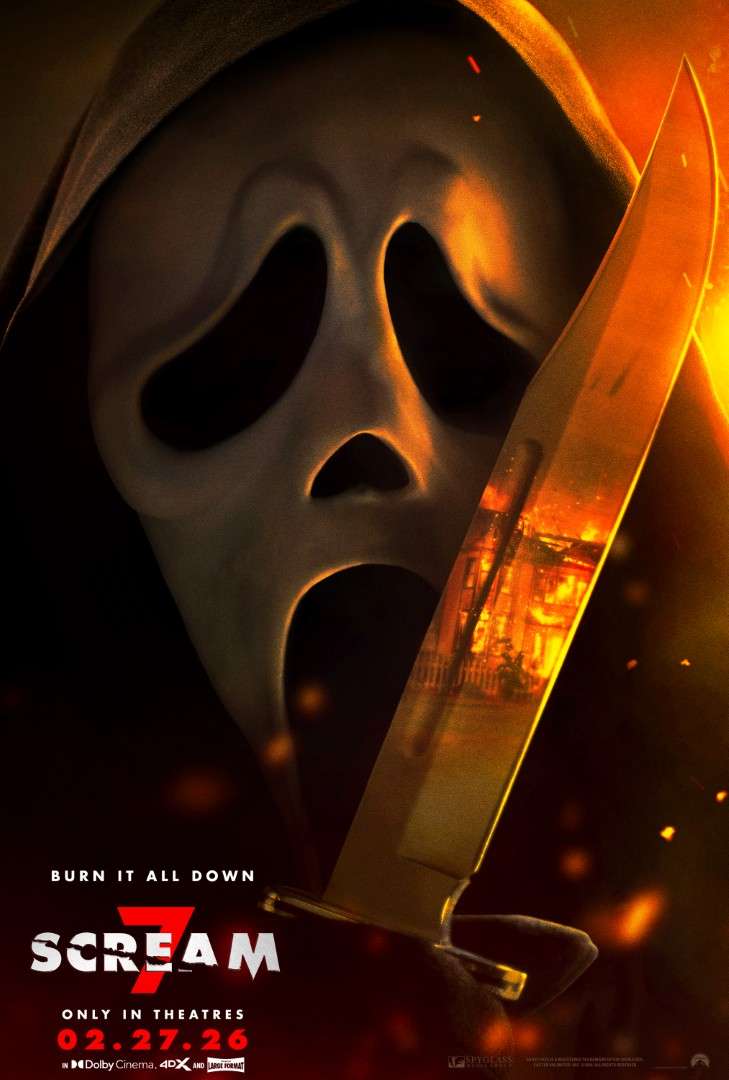

Sidney Prescott Leads a Brutal Throwback

Walking into Scream 7, I wasn’t sure if this entry would be a new reinvention. I know I wanted tension. I know I wanted that uneasy calm before the snap. And most of all, I wanted to see why Sidney…

Mar 13, 2026

Eggs – Film Threat

In writer-director-star James Clair’s short drama Eggs, a man struggling to rebuild his life finds his quiet mornings turning into strange conversations with the very eggs he is meant to cook. I mean, they want him to eat them. So…

Mar 11, 2026

Ethan Hawke Elevates A Rugged, Predictable Gold-Run Survivalist Western[Sundance]

As far as one can tell, Murphy (Ethan Hawke), a father, WWI veteran, and avid car mechanic, has never encountered an insurmountable challenge. Living in Eugene, Oregon, in 1933, four years into the Great Depression, Murphy and his young daughter,…

Mar 11, 2026